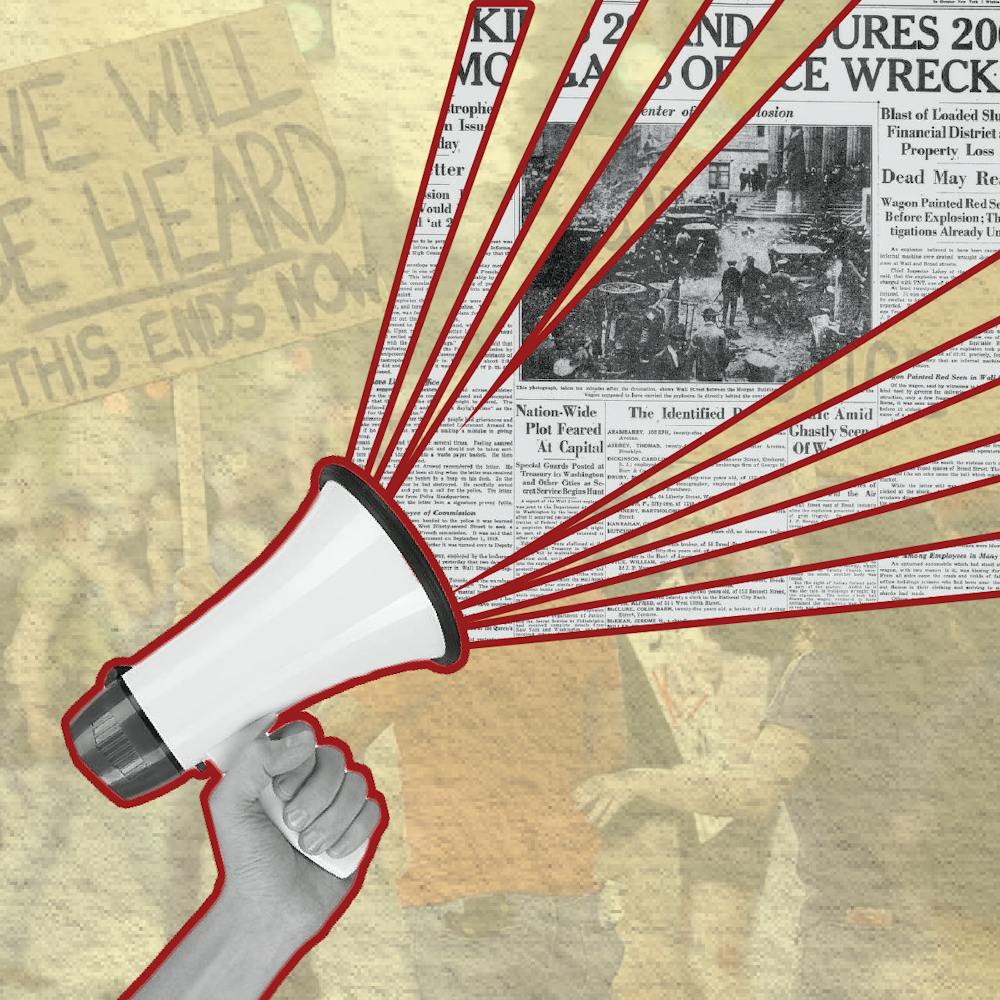

There is a second war happening in Russia: the war against information.

In 2006, the assassination of the journalist Anna Politkovskaya – an investigative journalist critical of the Russian government – cemented the shift away from a state of free information. While she was not the only journalist to be killed, her murder symbolized a chilling message: Criticize the government, and a target is placed upon your back.

The target then became much larger and more abstract, with government firewalls being put into place to block outside sources of information. As of 2024, over 300,000 websites are blocked in the country. Most relevantly, the Wikipedia page discussing the Russian invasion of Ukraine is blocked, as well as 110 other articles discussing information deemed. Roskomnadzor, the Russian government’s agency for media regulation, claimed the reasoning was “...illegally distributed information…”, but the claim is unfounded.

Independent Russian news organizations, such as Agentura, The Bell and the Moscow Helsinki Group (mhg.ru) are blocked, as well as international organizations such as the Human Rights Watch (hrw.org), Amnesty International and Ukrainian news, via Hromadske.

Additionally, there are bans in places for social media sites such as Facebook, Snapchat, TikTok, Instagram and YouTube, with the Kremlin claiming “discrimination against Russian media.” The only news left, such as The Moscow Times or Russia Today, is blindingly pro-government, with endless criticism for Ukraine and endless praise for the Russian efforts in the “special military operation” (the word ‘war’ is not allowed to be used).

It doesn’t take an investigative journalist to see what’s happening in Russia. The truth is outlawed.

To see the truth, you must know how to use VPNs, and most importantly, realize that the information you’ve been given is wrong. When you live in a place such as Russia, the truth must be fought for.

We, as students living in America, have access to the information people have been killed trying to reach. With the tap of fingers on keys or thumbs on a screen, we can find the truth from thousands of different sources. If you wish to see news critical of our government or news discussing U.S. actions that had massive negative consequences, it’s easy to find.

So why does it seem like nobody wants it?

Among young people, news consumption from traditional sources is startlingly low. A 2024 Pew Research Poll says that 46% of young people often watch television news, 27% use radio and only 18% use print news, while 91% cite using digital media to consume news. Scarier still, 62% of adults cite their primary news source as social media.

In this lies a larger problem. Traditional media is heavily fact-checked and runs through multiple editing stages before hitting the public eye, ensuring that the information within is true. Who, then, is fact-checking social media?

No one.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Because of Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, social media providers cannot be sued for perpetuating misinformation, and as such, there’s no motive for them to moderate what information is pushed out onto the site. This effect is worsened by the advent of engagement-based algorithms, locking consumers into echo chambers of what they choose to hear.

The lack of fact-checking on social media allows misinformation to be seen right alongside verified facts, placing equal value on the two. One could scroll through TikTok and see a video discussing the facts behind a new scientific breakthrough, followed by someone claiming that vaccines contain government tracking devices.

Scariest of all is how much of those false claims take hold. For one example, people are willingly drinking unpasteurized milk, believing pseudoscientific claims that it’s “better for your gut.”

To a frightening degree, the “truth” has almost become relative, with more emphasis placed on keeping users engaged rather than keeping users properly informed. All it takes is one lie to go viral, and the general public is latched upon falsehood.

The biggest problem is that it doesn’t have to be this way. We don’t live in Russia.

If you were to seek out nuanced, varied takes on world events from verified experts in their respective fields, you can find them with a simple search.

There are many options, too. In the U.S. alone, over 1,000 current news publications and thousands more international publications are accessible.

In a country where the truth is within reach, we, as young people pursuing higher education, often choose to consume our information from sources unconcerned with truth, when there’s much more verifiable information readily available.

Faced with a lake of knowledge to swim in, we splash in the muddy puddles left behind by acid rain, and if we’re not careful, that lake may dry up.

revella2@miamioh.edu

Anya Revelle is a first year majoring in political science. She is a student of the Honors College, as well as a member of the Honors Student Advisory and Activities Board. Anya is Russian-American and takes great care to be cognizant of both sides of herself.