In a packed lecture room in Laws Hall on Thursday, Nov. 15, renowned conservation biologist Joe Roman discussed “the wild future” of our planet, emphasizing wild animals’ power in shaping our world.

Introduced by Steven Sullivan, director of the Hefner Museum of Natural History, and Renata Crawford, Roman rang in the 50th anniversary of the Hefner Lecture Series.

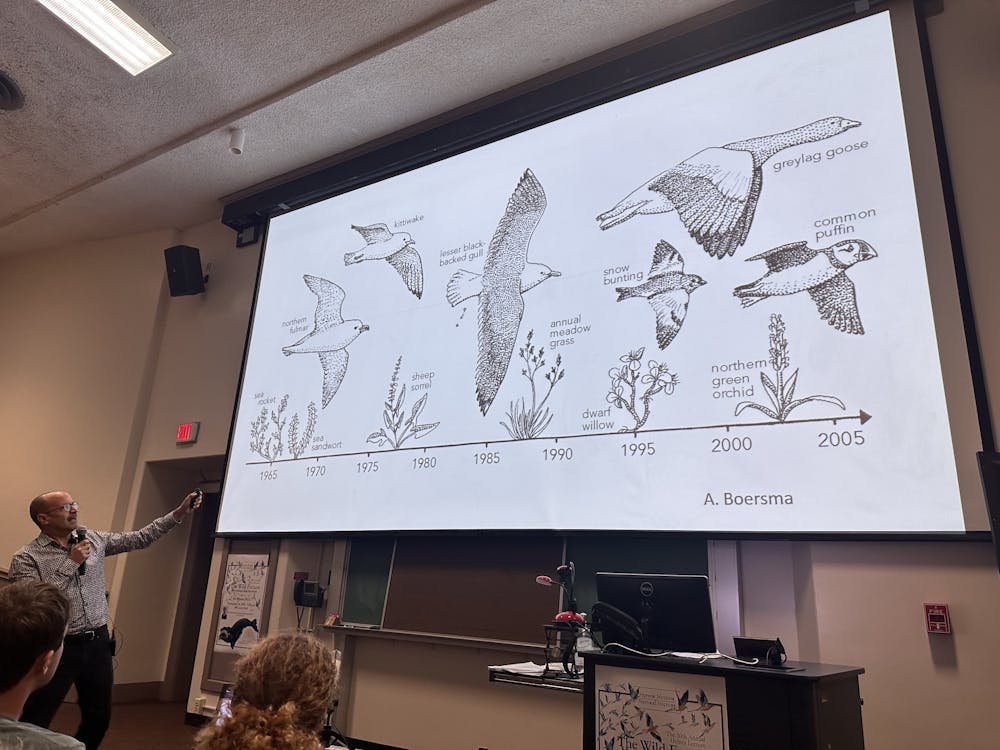

In the spirit of anniversaries, Roman began his lecture by celebrating the 61st birthday of Surtsey Island, a small island off the coast of Iceland. Born from the sulfur emitted from a volcanic eruption in 1963, Surtsey Island is known for its rapid yet desolate formation, except the island isn’t as desolate as it may seem at first glance.

“Things started to change when birds came,” Roman stated.

Oddly enough, that change was rooted in these birds’ poop — giving essential nitrogen-rich nutrients to the island that it once lacked. Roman said this change was specifically manifested at the pace of “one pasty poop at a time.”

Often, decay brings life, and this is exactly the case in nature. As these birds pooped, the nitrogen in their waste brought life to Surtsey Island, sprouting a variety of plants that made green what was once mere gray sulfuric rock.

“[Surtsey] is a perfect example of how animals shape our world,” Roman said.

Roman described the shaping power animals have to being akin to our planet’s “circulatory system” and the “heart of our planet.”

Bringing his lecture closer to home, he questioned the audience, imploring them to consider, “What animals can shape ecosystems in Ohio?”

The predominant responses ranged from white-tailed deer to squirrels, even including migratory species like birds. These answers led Roman to discuss his recent research on vertical migration and biological pump systems. These concepts encompass the vertical cycle of life and decay in the ocean, specifically how decaying organic matter — like poop — feeds oceanic life.

Roman discusses the importance of the biological and whale pumps for oceanic life and decay during his recent lecture.

However, when first learning of this concept, Roman felt that an important player was sidelined: the whale. He grappled with this thought for years, unsure of whether this research would be important after a colleague of his asked him, “Is this important or just a fart in a hurricane?”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Despite this uncertainty, a few years later with the backing of his colleagues, Roman tested the role whales play in the Gulf of Maine’s biological pump system. With his colleagues, he conceptualized the Whale Pump and the Great Whale Conveyor Belt after modeling and literally scooping up the nitrogen-rich impact whales have in the Gulf of Maine.

“We found that whales actually bring more nitrogen to the Gulf of Maine system than all the area’s rivers combined, contributing to around 24,000 tons of nitrogen per year to the Gulf’s surface areas,” Roman said.

Beyond this more narrow geographical scope of whales’ impacts, their positive nitrogen impact is spread worldwide.

“They travel thousands of miles every year in order to mate or to have their calves … providing the largest long-distance subsidy of nutrients of any animal on the planet through their urine, milk, poop and carcasses,” Roman said.

The cyclical power animals hold in their lives and their eventual decay, from the birds on Surtsey Island to the whales in Maine, inspired Dr. Roman to condense his life work down into three words, forming the title of his most recent 2023 novel: “Eat, Poop, Die.”

Roman concluded his lecture with a reality check. He said that while these organisms hold a lot of nutrient-rich power, wild animals only make up 4% of our planet’s biological life.

“My job as a conservation biologist is to try to nudge that four percent a little bit,” Roman said.

Opening up that onus to everyone present, Roman called for the audience to all play a part in that conservation.

“Let’s replace our carbon footprint with the tracks of wild animals,” he said.