David Russell and his students stand around in a circle, rolling hills and forest surrounding them in an open landscape down a discreet gravel road in Hueston Woods State Park. They are performing a point count, where they observe the skies and listen intently for bird sounds for five minutes, writing down every observation.

“Tennessee warbler, there’s a crow, there’s a cardinal, there are two crows, turkey vulture, there’s another turkey vulture, chimney swifts going over,” Russell said, observing many by simply hearing its call.

Russell, a Miami University professor and certified bird bander trainer, has been banding birds with Oxford residents and students at the Hueston Woods Biological Station for decades, collecting data and forming a tight-knit community in the process.

Russell and his students perform a point count, listening to bird calls to identify the species around them.

Most avian research stations are closed off and inaccessible to the public, in order to avoid the risk of naive posting online, which can undermine scientific integrity. Therefore, the stations often only recruit experienced bird banders, rather than training newcomers.

Russell looks at the situation a little differently.

“I take a different approach because I think it’s important that we bring students out, and we bring community members out, and I bring other college classes out because they don’t get this experience,” Russell said.

Bird banding involves attaching a small band to a bird’s leg to identify and track it via GPS. Researchers then measure the bird’s fat level, sex and age. This process allows researchers to examine migration patterns, population dynamics and mortality rates.

Russell started the station in 2004, two years after marrying his wife, Jill Russell, an associate teaching professor of biology at Miami. They wanted an activity they could do together despite her visual impairment. Bird banding, which Russell had already been long involved in, was the perfect choice.

The station, affiliated with the non-profit Avian Research and Education Institute that Russel founded, began with just 10 mist nets — 10 by 40-foot finely-woven nets designed for catching birds — and has since expanded to 40 nets.

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), bird banding does not harm birds when proper techniques and equipment are used. Certified banders like Russell are required to follow the Bander’s Code of Ethics, which mandates strict procedures and care for the birds.

“Bird safety is our number one concern because it would do us absolutely no good to do anything that would make their life harder,” Russell said, carefully untangling a Tennessee warbler from a mist net.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Every year, Russell collects data and sends it to the USGS Bird Banding Laboratory, which assimilates all the data collected from bird banding in the United States and Canada.

Hueston Woods, including the 10-acre area of successional, which refers to the new growth and changing vegetation, woods around the station, is a popular rest stop for birds migrating between breeding grounds in the north and winter habitats in the south.

Through his decades of banding, Russell observed a significant decline in bird populations. When the station first started, they would capture around 120 birds a day during the peak of migration. Now, that number is closer to 70.

“In essence, our numbers have dropped about in half, and you can see that across our data,” Russell said. “And that’s been true of birds overall.”

According to a study published in the journal “Science,” North America now has 3 billion fewer birds than 50 years ago, with one in four birds disappearing in the last half-century.

Russell is looking for ways to combat this decline in bird population by working with Hueston Woods to provide better bird habitats.

“Some of the management decisions we’ve been working on with the park is converting a lot of the area that has been overrun with non-natives to our native spice bushes and our native dogwoods and things like that, to help what is appearing to be a problem for some of our migrant species,” Russell said.

Russell’s efforts have attracted the attention of Andy Rice, an associate professor of media and communication and film studies at Miami. Rice has been following the group for years and is filming a documentary about them.

The documentary, titled “Banded: How a Birder’s-Eye View Made a Community,” goes in-depth into Russell’s bird banding process and the community members involved. The film will be screened at the Wildlife Conservation Film Festival in Monterrey, Mexico on Oct. 24-27.

Along with community members, Miami students also help at the station. Not only are students in Russell’s classes involved in banding, but the station also provides immense opportunities for students to do their own research and projects.

Ginny Boehme, the biology librarian for the group, is currently developing a visual manual, as opposed to traditional text-heavy ones, to teach people bird banding.

“We want to try and take pictures of all these birds and present them in a more easily digestible format,” Boehme said.

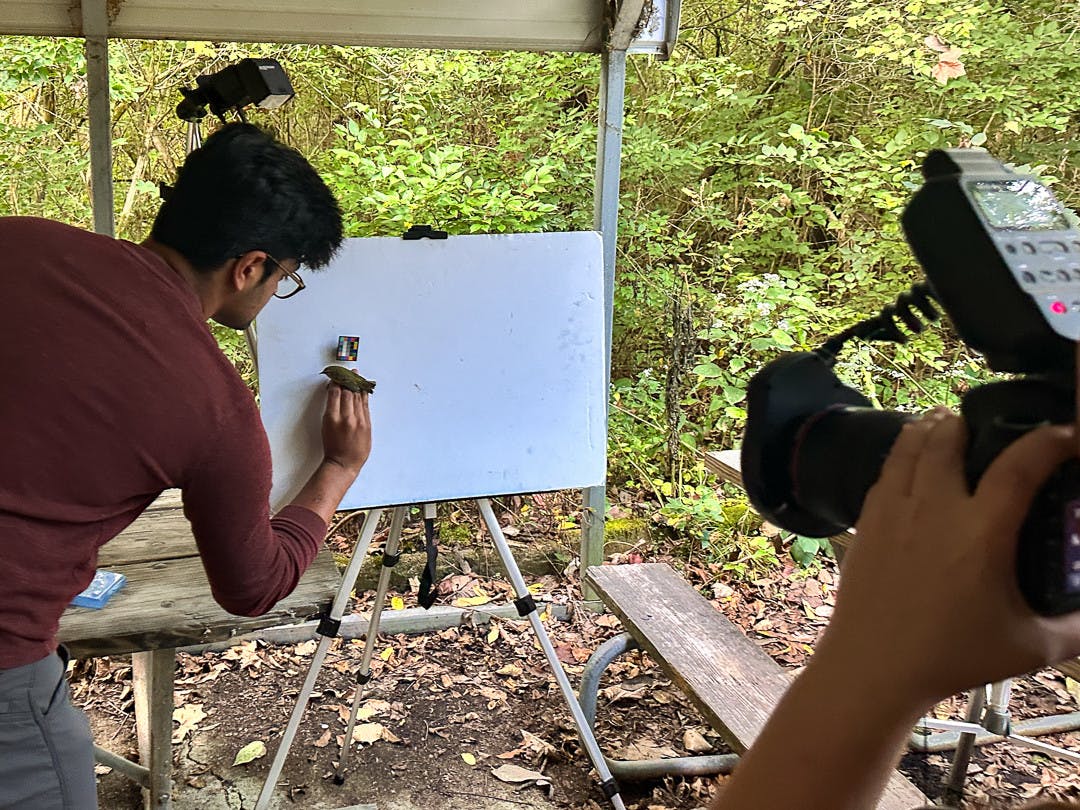

Students display a bird next to a color gradient to help create a visual birding guide.

Dhruv Iyengar is a graduate student who has studied abroad in Ecuador, making a template for bird banding there, is also involved in the visual manual. He explained that examining birds’ feathers is vital to determining their age, but teaching others is difficult.

“Those feather differences are so fine that it’s really hard to teach new people what to look for,” Iyengar said. “So the idea is we take pictures of all our birds, and we correct the lighting to get those colors to pop out, to make them easier to teach.”

Along with graduate students, undergrads also have opportunities to gain experience with bird banding. Madalyn Couch, a junior zoology major, said she first got involved with Russell’s bird banding through a field ecology class to collect data for a report. She decided to come back a second time to get more experience.

“[In] a lot of field technician positions, there’s a lot of bird banding involved,” Couch said. “They’re important to study because they relate to insects a lot too and the ecosystem as a whole. It helps, in the future I will likely have to do this as well.”

Russell examines a warbler, of which many different species call Hueston Woods home. Photo provided by Andy Rice

Russell said he has noticed the interest in birding growing in Oxford. There is a birdwatching station located just north of the DeWitt Cabin Log House, and there is also a bird club at Miami.

“I think it’s become prevalent because it combines getting outdoors with a subject that requires some knowledge, so you actually have a challenge to it,” Russell said. “Why do people play Pokemon Go? [It’s] because it’s a game of getting out and doing things and birding is very similar to that.”

Russell said getting people to the bird banding station for whatever reason, whether it be for research purposes, to see his two Bernese mountain dogs or to see friends, has helped contribute to the local conservation efforts around Oxford.

“These are the same people that if you put out a notice [saying], ‘Hey we need volunteers to help remove honeysuckle’ [or] ‘We need volunteers to work at a booth or to lead groups around,’ these are the people who are happy to do it,” Russell said.