Attendees of Rebecca Nagle’s lecture on March 8 left with more than just knowledge about tribal sovereignty — they learned why they should care.

The lecture, hosted by Miami University’s Western Center for Social Impact and Innovation in collaboration with the Myaamia Center invited Nagle to speak on tribal sovereignty in the modern age.

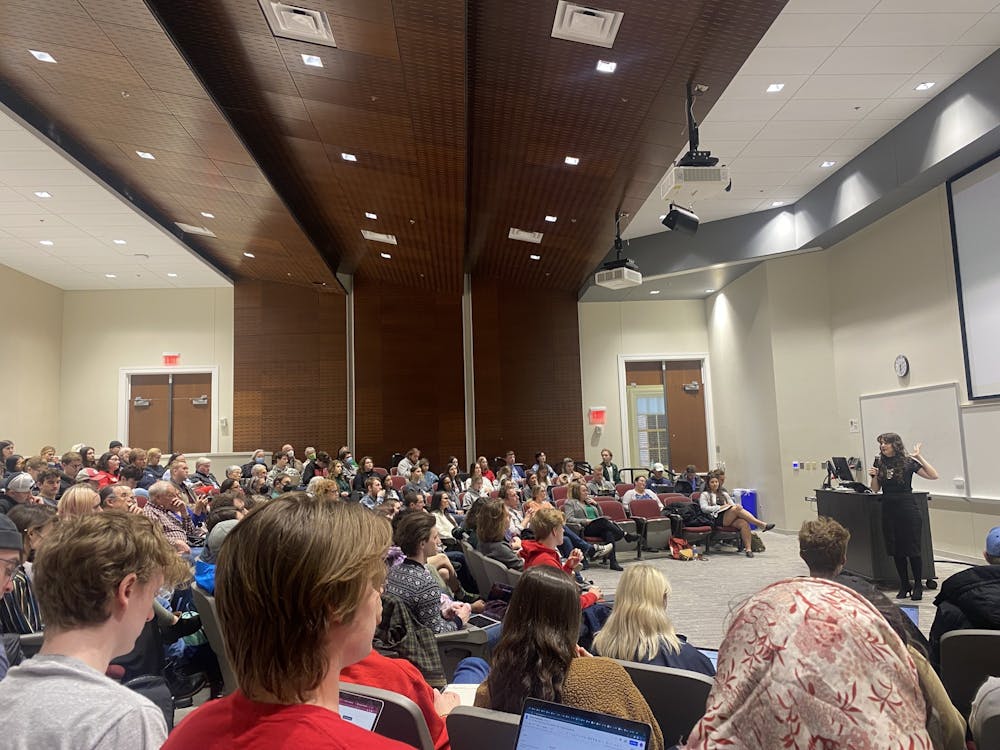

Nagle, an award-winning podcaster and citizen of the Cherokee Nation, spoke to a full audience in Shideler Hall about what it means to be a federally recognized tribe, how U.S. policy impacts the rights of tribes and their citizens and the underrepresentation of Native Americans in the media.

Kara Strass, director of the Miami Tribe Relations Office, and Jackie Daugherty, director of the Western Center for Social Impact and Innovation, each gave introductions discussing the work of the Myaamia Center and Nagle’s recent advocacy work to end violence against Native women.

“Rebecca’s work aligns well with our university’s current focus theme of tribal sovereignty and the Western Center’s current work on reparative justice efforts,” Daugherty said.

Nagle began her lecture by discussing the lack of Native representation in the media. She said Native people make up 2% of the U.S. population, yet less than 0.1% of people in movies, television and music are Native.

“If you think about that, every time there’s a Billboard Top 100, two of those should be by a Native person, right? When you’re scrolling through Netflix, one out of every 50 shows should be centered on a Native story,” Nagle said. “Instead of even getting just that 2%, which I think we’re owed more than, it’s always a fraction of a fraction.”

Nagle also said that when people think about Native Americans, they tend to think of them as a thing of the past. Of the top 100 Google image search results for Native American and American Indian, 95% are from the late 19th century, Nagle said.

Nagle said this lack of representation creates harmful stereotypes. She cited one study that conducted interviews across the country and found that many people didn’t even know Natives are still alive.

“There was recognition of ‘Yeah, this happened in the past, that was bad,’” Nagle said. “But Native rights and issues aren’t a contemporary issue in our country today. And how can you blame them because the news media and the press are not telling them about the issues Native people are facing?”

Kristen Impicciche, a senior communication design major, works at the Western Center and helped put on the event. She said she appreciated Nagle encouraging the audience to follow Native American media organizations, including Indian Country Today and Native News Online.

“I thought that was really interesting because you don’t really see [Native news] day-to-day,” Impicciche said. “We should let those voices be heard more and lift them up.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Nagle pointed to the widely uncovered effects of COVID-19 on Native people, who are often grouped into an ‘Other’ category for demographic case data. In an analysis by the Washington Post from August 2021, one in 1,300 white people had died of COVID-19, while one in 240 Natives died.

Much of this lack of attention to Native issues, Nagle said, is due to a widespread lack of information about how Native tribes continue to live and function in the U.S. today.

“How many people [here] know legally what a federally recognized tribe is?” Nagle asked the crowd. “How many people feel like they can name one Supreme Court case that impacted Native people in the U.S.?”

Only a few people raised their hands.

“You all didn’t just fall into not knowing what tribal sovereignty is — it’s systemic,” Nagle said. “What is happening in our culture now is the type of racism that functions through invisibility. Native people are completely erased from pop culture, from media, from education, and that erasure creates a deep stereotype in the minds of non-Native people.”

Nagle then explained that tribal sovereignty is basic civics; it’s a layer of government, just like local, state and federal.

“In Oklahoma, tribes are paving roads, providing health care; they have their own police force,” Nagle said. “We’re doing a lot of the work of local government.”

Indigenous rights also work differently, as they’re more centered around collective rights rather than individual ones. The right to sovereignty, Nagle said, is something that is inherent rather than something that is given to Native nations by the U.S.

“Our Native nations predate the creation of the United States,” Nagle said. “Our right to our lands, to our culture, our own self-governance and self-determination, is something that has existed since the beginning of time.”

Although colonization has impacted how much of that sovereignty can still be practiced today, Native tribes have worked hard to be recognized in U.S. law through Indigenous activism. In the U.S. today, there are more than 570 federally recognized tribes, each with its own system of government.

Treaties, Nagle said, are another aspect of Native history riddled with misconceptions.

“People have this idea that treaties are sort of these outdated and antiquated promises, and there’s this given that treaties are broken or aren’t followed,” Nagle said. “If you look at the Constitution, it says that treaties are the supreme law of the land.”

Known as the Supremacy Clause, a portion of the Constitution states that if the U.S. signs a treaty, it can’t be repealed by the courts, state governments or even legislative bodies. Nagle said it’s frustrating how often Native rights outlined in treaties are infringed upon.

“I like to joke sometimes that the U.S. federal government created this entire legal framework with which to legally seize our land according to its own laws, and then doesn’t even follow those laws,” Nagle said.

Some of Nagle’s own family members signed a treaty that gave the Cherokee Nation the right to a non-voting delegate in Congress in the 1780s and was affirmed in 1835. That delegate has never been seated.

Although Nagle’s talk was, in her words, “a bit of a downer,” she ended on a positive note by highlighting some of the positive changes happening currently, catalyzed by Standing Rock.

The Standing Rock Indian Reservation, located on the border between North and South Dakota, received national attention in 2016 when its tribal members protested the Dakota Access Pipeline, which they considered a dangerous threat to the area’s water.

“Not only are Native people still here, but our tribes are still fighting for these basic things like land and sovereignty and safe drinking water and treaty rights,” Nagle said. “The attention that moment captured has built momentum for things that have come since then.”

Rylee Domonkos, a junior software engineering and business analytics major, said she attended the event for her Introduction to the Miami Tribe of Ohio [HST 259] class.

“Tribal sovereignty is a big thing that we’ve been discussing in the class,” Domonkos said. “So it’s interesting to hear a more modern take on it rather than just looking at the late 1800s, early 1900s which is where [the class] is at now.”