Out of all Miami University faculty, 83% are white. Although a large majority, this proportion is only slightly more than most higher-education institutions in the U.S.

But industry-wide problems don’t always require industry-wide solutions.

Andrew Jones, an assistant professor of chemical, paper and biomedical engineering, said it’s important to have diverse faculty that can act as mentors for students of all backgrounds.

“That doesn’t mean that people that [are white] can’t be those role models and mentors,” Jones said. “It just makes it a little more difficult because we haven’t lived the same experiences and can’t always relate in the same ways.”

Jones, a Pell Grant recipient, said his background coming from a lower socioeconomic status has helped him build rapport with some of his students.

“I’ve had students that have shared that they’re in that space where I’ve been able to say that I also came from a low-income family as an undergraduate,” Jones said. “And that’s not something you can tell by looking at my faculty profile.”

Beyond student interaction, Jones said having diverse faculty can directly affect policy making.

“We need diverse voices in the room while those decisions are being made,” Jones said. “Somebody to say, ‘We shouldn’t require students to take 19 credit hours in a given semester.’ And somebody from a wealthy background might say, ‘Well, just take 16 and take a class over the summer,’ but might not realize that the $3,000 it costs to take that class is not an option for a lot of students.”

Diversity can have benefits in other areas besides teaching positions as well. Tammy Brown, an adjunct clinical instructor in the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology, said her experience growing up in poverty helps her treat and interact with the socioeconomically diverse community in Oxford.

“I have patients come in all the time who are farmers or factory workers, who are having difficulty with their kids or with understanding hearing loss and speech impediments, and I can relate to them,” Brown said.

Brown said her ability to relate to her patients helps them trust her, allowing them to work together to get to the root of problems and identify solutions.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Taylor Rothman, a senior chemistry major with minors in marketing and general business, said most of her professors in both the Farmer School of Business (FSB) and the College of Arts and Science (CAS) have been predominantly white and male, but she’s had more female faculty in her business classes.

“It’s nice when I have a female professor because I know her specific experiences are kind of unique to what I’ve experienced as a woman,” Rothman said. “When [a faculty member’s] background or their experiences align with yours it’s helpful, no matter what class it is.”

Rothman said while she’d like to see more diversity in her faculty, she wonders if the lack of such is connected to the lack of diversity in Miami’s student body, which is 76% white.

“I think Miami’s reputation is predominantly white, and maybe the school attracts more white professors for the same reasons it attracts more white students,” Rothman said.

Stephanie Danker, an associate professor of art education, said bringing on more diverse faculty could improve Miami’s student diversity as well.

“It says a lot about the values of a department, of a college, of a university, to have diverse representation of faculty members,” Danker said. “I think it makes a difference when prospective students are looking at our faculty makeup and they’re deciding between colleges.”

While Miami’s faculty demographics have homogenous aspects, they’re comparable to similar nearby public institutions. At Ohio University, for instance, members of minority groups make up 16% of total faculty, roughly equal to that of Miami.

Jones said part of a school’s demographics may be due to factors like location.

“The universities I’ve been at looked pretty similar [to Miami],” Jones said. “Especially considering we’re a rural public school in Ohio. I think if you were to look at an elite private school in, say, Boston, they likely have a faculty and a student body that’s more diverse.”

Other factors, however, are more controllable. Danker said she’s been impressed by the efforts of the Office of Institutional Diversity and Inclusion (OIDI) and the College of Creative Arts (CCA) to increase faculty diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI).

“There are all kinds of training being offered,” Danker said, “which are super important for faculty to be encouraged and required to take to recognize their own biases and really become more open-minded and better colleagues and better mentors to students.”

To bring diversity into her own classroom, Danker partners with The Myaamia Center, whose co-teachers come in to teach students about Myaamia culture.

Christy Carr, assistant teaching professor in communication design, said increasing faculty diversity may require financial solutions.

“I think in order to attract a demonstrably diverse community of educators, you have to be willing to invest in them, in their salaries and their professional endeavors,” Carr said. “There are probably other organizations out there who are willing to invest in it and put the dollars behind it.”

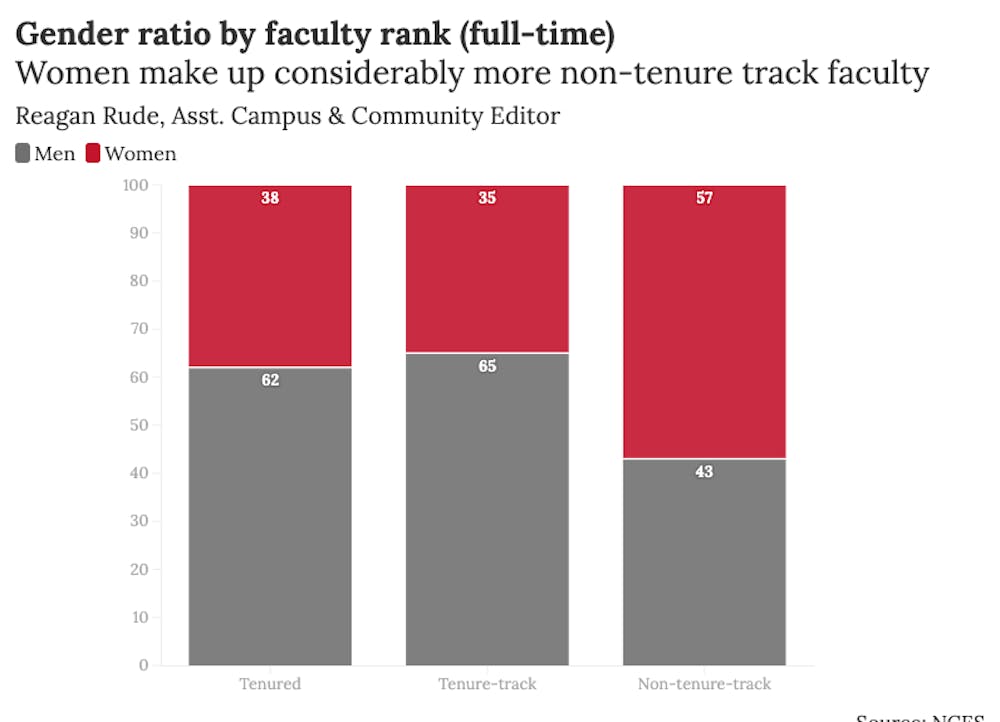

Although gender diversity has notably improved, there’s still a sizable difference in the proportion of female tenured faculty compared to non-tenure-track. At Miami, women make up 57% of non-tenure track faculty and 38% of tenured faculty.

Carr said part of this gap may be because the burden of domestic labor often falls on women.

“I’m Gen X, so I’m part of a generational system that rewarded people who didn’t have to interrupt their careers or their research or studies to care for their children or family,” Carr said. “I’m hopeful that that’ll change.”

Carr was working as an associate professor at the Art Academy of Cincinnati when she earned a sabbatical, and chose to take a full year off instead of six months to care for her two kids. She said many women who take time off for domestic responsibilities lag behind their male counterparts in salary for most of their careers.

“You see the pay inequity,” Carr said. “We’re still not making anywhere close to what men make on the dollar. And then we have interruptions because the responsibility of family falls on us, and it creates a glass ceiling.”

Carr, who previously worked in consulting, said the private sector allows for salary negotiations, where applicants can leverage their experience for a higher salary. At Miami and similar institutions, these negotiations aren’t prohibited, but they don’t often boost salaries for contracted positions.

“It’s like, this was the job that was advertised. This was the salary that corresponds with that level of employment. And whoever accepts that position, that’s the salary,” Carr said.

Carr said deeper conversations about diversity at Miami may be needed to see progress.

“If we want diversity, then we have to be looking at the system by which we’re bringing people in and is it fair, and what ways could it be made more equitable,” Carr said. “We’ve got to start acknowledging the elephant in the room.”

If faculty diversity is improved, some think it could affect which students choose to enroll at Miami. Jones said a more inclusive atmosphere for faculty may improve the experience of diverse applicants as well.

“Miami admits a large majority of people that apply and then get a pretty low yield off of that,” Jones said. “And the question is, if we get people to campus, can we show them an environment that makes them want to come here?”