Paula Smith was raised in Oxford, Ohio. Her parents, who founded the Allen Foundation which offers refuge to Black Miami University students, both worked for the university. Although Smith attended Ohio University for her undergraduate degree, she did come back to Miami for her Master’s.

Smith represents one of the few Black people associated with Miami’s Oxford campus. Based on data from Oct. 15, 2020, Black and African American students account for only 3.6% of the Oxford campus student population. Compared to the 75.5% of students who identify as white, this makes Miami a predominantly-white institution (PWI).

Smith was one of the oldest living alums interviewed in a new documentary, titled “Bittersweet,” which was created by faculty, staff, students and administrators at Miami. Smith was one of the first people interviewed for the documentary. By the time the documentary was released, however, Smith was losing her memory.

Part of the purpose of the documentary was to try to capture stories from Black Miamians like Smith before they disappeared.

The documentary was part of a project called Lived Experiences which seeks to explore the lives of Black students at a PWI. The project was funded through Miami’s Boldly Creative program, which invested $50 million to projects that usher “a new generation of academic excellence,” the website reads.

The documentary was co-produced by Seth Seward, assistant director of alumni relations, and Andy Rice, assistant professor of media and communications and film studies. Rice also directed the documentary, which combines footage, interviews and photos that detail the lives of Black Miami students, faculty and staff, past and present.

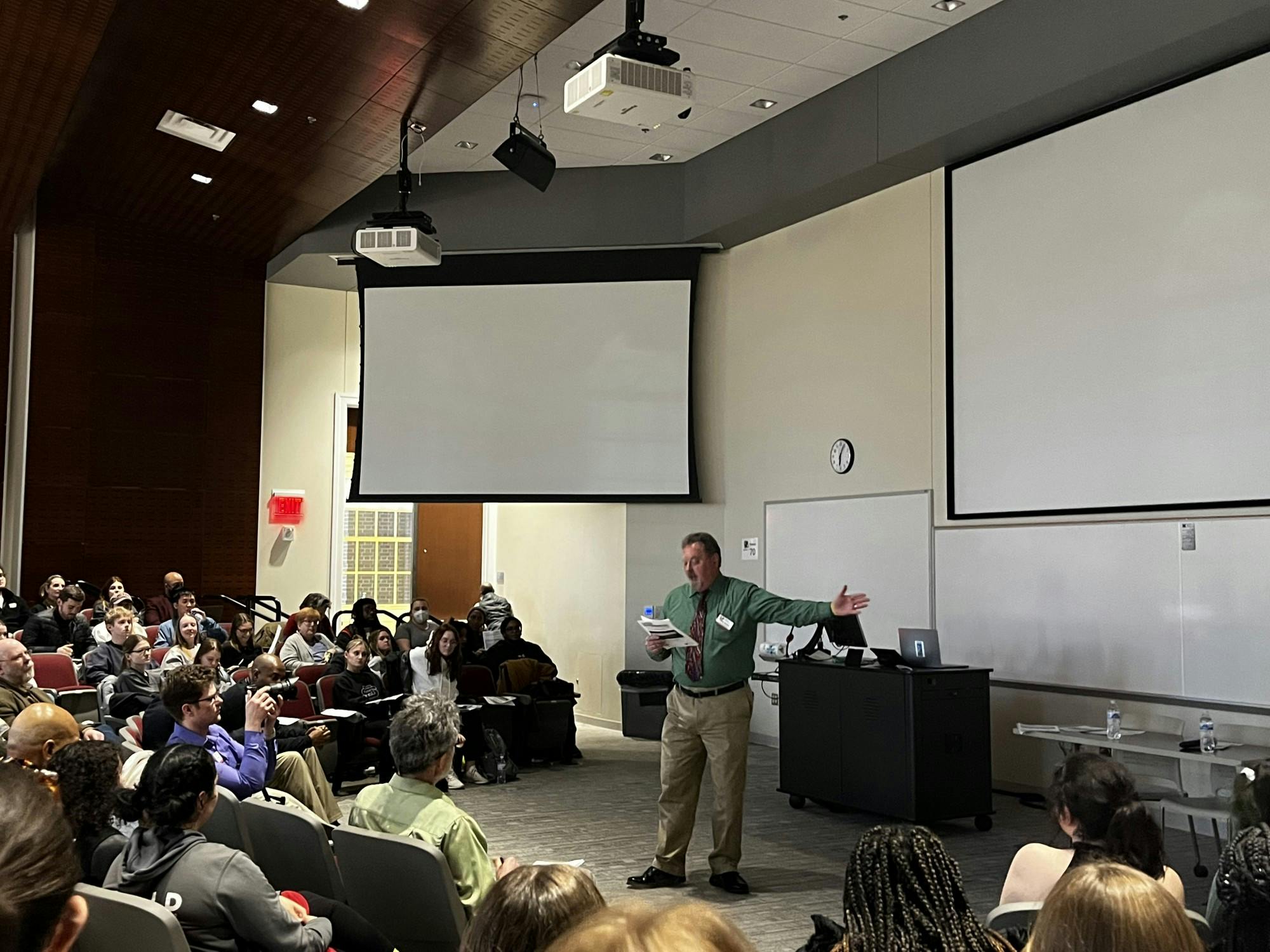

William Modrow, head of the Walter Havighurst Special Collections, introduces the documentary to a full crowd.

The documentary premiered Feb. 22, in the Shideler Hall multimedia auditorium to a full room. The film was followed by a Q&A session with Rice, Seward and two students who helped produce the film, Anika Elias and Maggie Peña.

During the Q&A, Rice shared that Seward was integral to the documentary’s creation. He also said Paula Smith, the oldest living interviewee featured in the film, played a similar role.

“[Seward and I] worked on all the interviews together. Seth was, for the most part, the person asking the questions, the glue to make that film all come together,” Rice said. “For me, he’s the soul of the project. Paula’s the structural backbone.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Rice also said some of Smith’s photos made him realize that even though the documentary required a large amount of research, it’s only able to capture a limited part of history.

“It got me wondering how many more photos are in those basements somewhere that have this rich history that could just fade away,” Rice said. “It takes commitment and resources to put a project like this together.”

Rice elaborated on this idea, saying how the documentary helps to preserve history, using the footage from the film of an interview with three Black administrators at Miami as an example.

“Having these interviews was invaluable,” Rice said. “The initial interview with the three African American administrators, those three people, they’ve all passed. That’s it. There’s not going to be another conversation with those folks. And so to be able to piece together institutional history in the trenches was incredibly valuable.”

Elias, a senior political science and strategic communications major who served as co-editor for the film, agreed with Rice.

“It’s kind of like an ‘If not now, when?’ question,” Elias said. “We’re on a time crunch in terms of trying to preserve this history and trying to make it so people of my generation and generations after us can understand what happened to the people that came before us.”

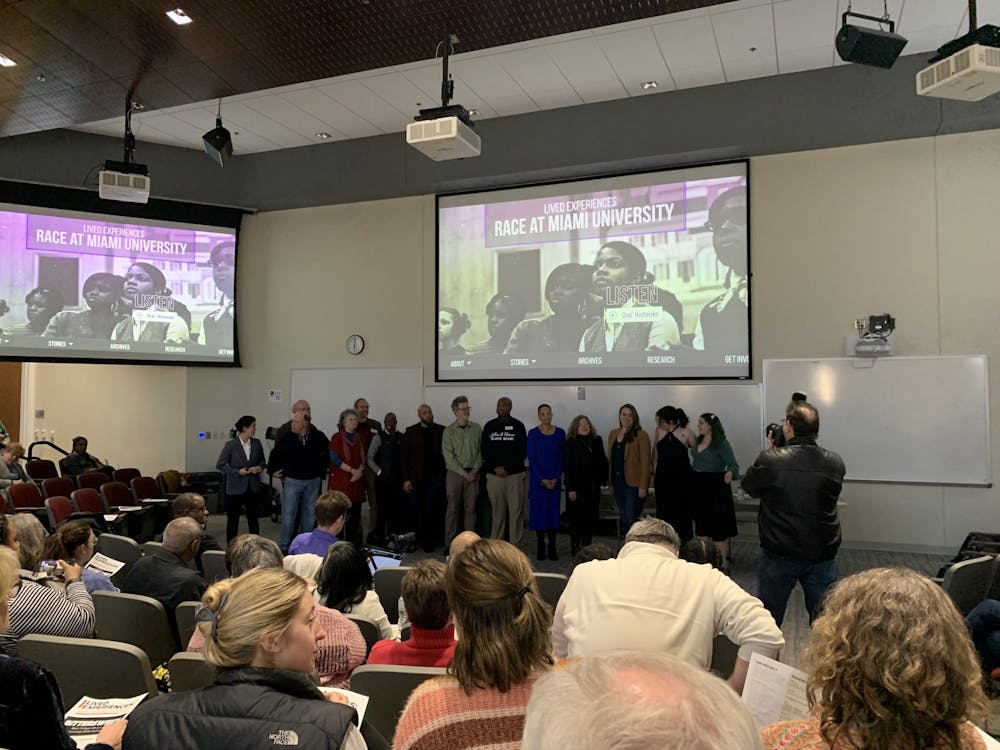

From left, Yvette Harris, who was part of the core team for the Lived Experiences project, leads a Q&A session with the people who made "Bittersweet," Andy Rice, Seth Seward, Maggie Peña and Anika Elias.

Even though the documentary uses research to provide historical background on Black life at Miami, it also gives a glimpse at how that has shaped life today, Seward said.

“We have to capture history while it’s there,” Seward said. “Folks are saying stuff now [that] provides more context to that, and [we] see how things came about, how things are still the same, maybe how things may have changed a little bit.”

The documentary, Seward said, aims to show how campus life has evolved at Miami for Black students.

Yvette Harris, the psychology program coordinator at Miami who is Black herself, worked on the Lived Experiences core project team. After the screening, Harris said even though the documentary is historical, its importance is in the present.

“The historical and contemporary perspectives are incredibly important,” Harris said. “The story still continues in terms of similarity. It’s just the decade in the context that changes, but the experiences as students of color tend to persist.”

The film emphasizes the idea of taking the history into the present by incorporating footage from early screenings of the documentary, followed by discussions from current Black Miami students.

Seward said these scenes are important because they allow current students to give their voice alongside past Miami students.

“They’re still having issues here,” Seward said. “It’s not a perfect situation for them. They're still having some experiences, and some others, they've found their community, they're having a good experience”

While working on editing the documentary, Elias and Rice had to find a way to piece together a narrative from footage, research and stories ranging from the first Black students on campus to present day interviews.

Elias said the key was finding connections between their stories.

“You see so many people who have recurring experiences, like the KKK marched here in 1958, but they also marched here in 1993. People not wanting a Black student to be their roommate, that happened in 1970, but that also happened today,” Elias said. “Figuring out how we wanted to approach that was really interesting.”

The documentary’s title, “Bittersweet,” which is said multiple times in the film, also plays an important role in tying these stories together.

The title represents a theme, that Black students at Miami, while sometimes able to find community, still struggle in various ways to live at a PWI.

“Black folks are trying to make the experiences work,” Seward said. “We see the similar themes of minority representation of faculty and staff and the experiences in the classroom. We see that that's the same experiences that we've had over the years and some of the painful experiences of that. But we also acknowledge the public ivy, the top 50 public schools in the country, very successful alumni that come out of the institution.”

Allison Sifri, a senior political science major, came to watch the premiere because one of her classes was offering extra credit for attending. Sifri also knows Elias.

Sifri said the documentary was insightful for her because of its in-depth research.

“Anyone with a brain could see that there’s a lot of racism here, and the Black students here are very isolated and oppressed in a lot of ways,” Sifri said. “The history, though, was something I didn’t really know about because you can’t Google that history, and a lot of what they talked about was all something that they had to dig up with archives.”

Seward reinforced the importance of the documentary, saying it gives a more accurate and multi-faceted depiction of Black life than other forms of media.

“What people see, you know about Black people from popular media, and that’s not always authentic,” Seward said. “The Black experience is not a monolithic experience, what you see through media. We don’t all believe the same; we don’t speak the same.”

The full documentary will be posted to the Lived Experiences website at a later date. In the meantime, the website has documentary shorts called “Trailblazers” of Black Miami faculty and staff who “changed Miami and the larger community for the better.”

Maggie Peña is an editorial staff member of The Miami Student.