Student burnout is at an all-time high. Mixed-format classes have made it harder for students to learn material. Soaring mental health issues and poor outlooks for the future are hampering motivation and work ethic.

With this in mind, Miami University has developed new methods to protect students’ GPAs and ensure academic success.

The divisions of Student Life, Academic Affairs and Enrollment Management and Student Success (EMSS) have teamed up to implement several strategies to prevent students from reaching these standings.

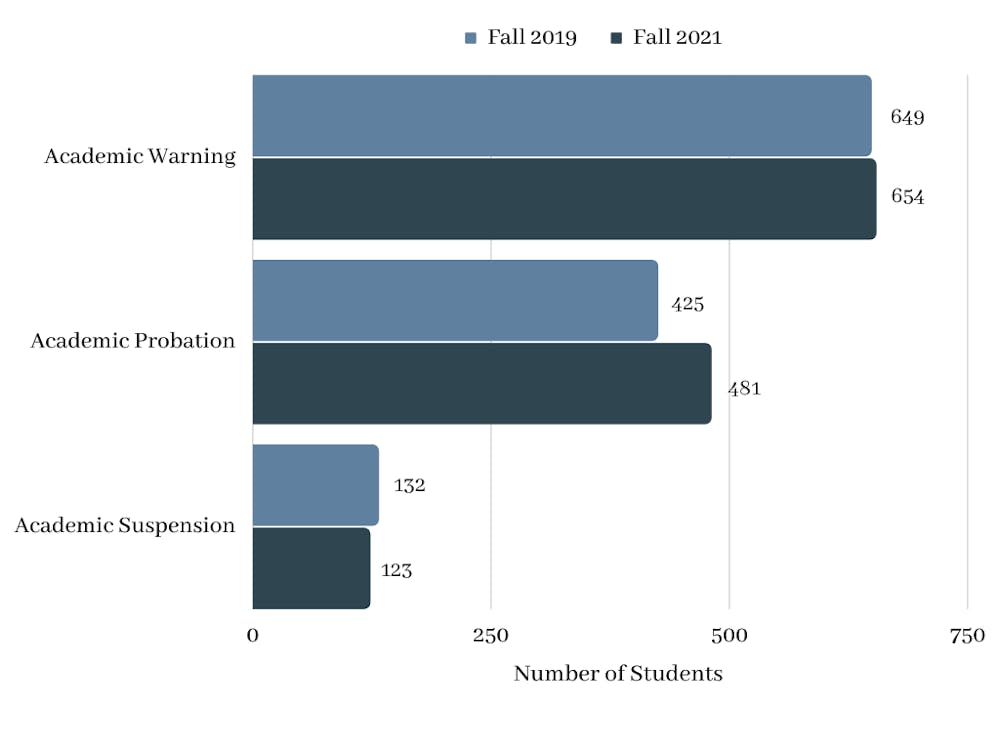

During the fall semester, more than 650 students were placed on academic warning – earning less than a 2.0 GPA and having less than 16 credit hours. About 480 students were placed on academic probation – earning less than a 2.0 GPA and having more than 16 credit hours.

Both of these were only marginal increases when compared to fall 2019, a non-COVID semester.

Despite the pandemic’s toll, students put on academic suspension slightly decreased this past fall.

Duane Drake, director of operations for EMSS, said the number of students who receive 0.0 GPAs has stayed about the same as well.

“This past fall, we had 48 continuing students and 10 new students that got 0.0s,” Drake said. “Over the past several years it’s gone up or down, but in that same range.”

Brenk Shock, vice president of EMSS, said Miami has implemented initiatives that work with students from the very beginning of the semester to curb grade issues from arising later on.

“As a university, we are getting much better at proactively identifying and working with students who might be in trouble early on,” Shock said. “All three divisions work in concert together to lift up and build up student success across the university.”

One initiative the divisions piloted this fall is an early alerts program that works with professors to identify struggling students early on in the semester. In the first two weeks, professors are asked to identify if students are attending class, have access to course materials and are engaged in the class.

In the fifth week, professors are asked again to indicate if they’re concerned about any students, as well as whether any students may need to consider withdrawing from the course.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

The students identified by their professors are given the option to drop the course and enroll in a sprints and reserve course instead. These courses count toward the Miami Global Plan and degree requirements and can be started in the middle of the semester.

Amy Bergerson, associate provost and dean of undergraduate education, said the university has seen great results from the program so far.

“The students who took advantage of that option … were [enrolled] at a much higher rate this spring semester and also had higher GPAs than students who didn’t take the option,” Bergerson said.

The offices also look at midterm grade reports and reach out to students who are failing two or more courses.

“We do proactive outreach to every single one of those students,” Bergerson said. “Academic advisors, the Student Success Center, and Rinella are all calling, texting, emailing these students and trying to figure out what’s happening and offering them various kinds of support to try to pick things up for the rest of the semester.”

Christina Carruba-Whetstine, director of the Rinella Learning Center, said the number of students who are reached out to after midterms is high, but the majority are able to recover by the end of the semester.

“The number of people that end up in [academic] warning or probation is really just a fraction of those who are not doing well at midterms,” Carruba-Whetstine said.

Carruba-Whetstine attributed the high recovery rate to the extensive outreach done to connect students to the right resources, such as tutoring, counseling services or the new sprints and reserve initiative.

If students do end up with an academic warning, they receive a detailed email from the university explaining what the status means and what steps they should take to return to good standing. They are also invited to meet with an academic advisor.

Students who end up on academic probation are automatically registered for a study strategies course.

“It is a very invasive [process],” Carruba-Whetstine said. “We’re on top of it saying, ‘We think that this is important and valuable and want you to engage with us.’”

Carruba-Whetstine said that while there are many factors that may result in students receiving low GPAs, mental health is the one most cited.

“[Sometimes students] get into a hole and don’t know emotionally how to get out of it,” Carrubba-Whetstine said. “They also, a lot of times, stop talking to their parents about how they were doing in school and just kind of check out.”

Another common trend involves students choosing a major without enough information.

“They think they know what it is, but then they get into it and they’re like, ‘No, this isn’t what I thought it was going to be at all,’” Carruba-Whetstine said.

Carruba-Whetstine said she often sees this with students going into engineering because they like building things, but don’t realize the amount of high-level math involved.

“I see that also with a lot of students who say they want to go into pre-med because they want to help people,” Carruba-Whetstine said. “There are lots of ways of helping people, not just surgically or medically.”

The effects of the pandemic on high school preparation has impacted student performance in college as well.

“School wasn’t the same for their last year and a half,” Carruba-Whetstine said. “What was expected of them in high school wrapping things up was not preparing them necessarily well for a lot of … high stakes kinds of exams.”

Bergerson said the shift from high school to college can be difficult for anyone, even before the pandemic.

Sometimes, Bergerson added, all it takes is missing one assignment, possibly due to being sick or not knowing how to do it, for a student’s workload to spiral out of control.

“Sometimes it’s just that one thing that triggers this crazy avalanche,” Bererson said, “and that’s really what we’re trying to look for in those early preventions is people who have signals that that might be happening.”