Three years.

That’s how long Miami University’s energy co-major has to grow from 25 total students to 20 per class, or it may disappear forever.

“We’ll give it a go,” said Jonathan Levy, director of the Institute for the Environment and Sustainability (IES).

For Levy, the energy co-major stands out from environmental science programs at other colleges.

“I wouldn't go so far to say that [the major is] unique, but I think the energy co-major is unusual,” Levy said. “I think that there are a lot of jobs in the energy sector for which that co-major would be useful on someone’s resume.”

Levy said students could pick up sustainability or environmental science co-majors with an emphasis on energy, if the co-major gets cut. If another program was at risk, though, the story would change.

“If sustainability was going away because we didn't have enough members, I would be terribly concerned about that, because I think some things need to exist no matter what the numbers are,” Levy said. “ … How in this day and age could you argue that [sustainability] doesn't belong in the university setting?”

The numbers that put the energy co-major on the endangered list came from an academic review process called “Academic Program Evaluation, Improvement and Prioritization” (APEIP), that began in fall 2019.

Since then, energy hasn’t been the only program to face elimination.

The team

In June 2019, the Board of Trustees approved the Strategic Plan, a list of 30 recommendations for Miami to prepare for the volatile future of higher education. Points 19 and 20 called for curriculum reviews of all undergraduate and graduate programs, laying the groundwork for APEIP.

“In order to grow strategically, resources must be reallocated,” the Board wrote in the Plan. “ … We do not have the luxury and financial capacity to be all things to all people.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

On Aug. 1, 2019, Jason Osborne’s first day as Miami’s Provost, he inherited the Board’s recommendation for “a committee appointed by the provost to oversee this review.”

Osborne appointed Stacey Lowery Bretz, a professor of chemistry, as committee chair.

She led a team of two additional provost appointees, five faculty members from University Senate, two student representatives and an additional seven division representatives – one from each academic college plus the graduate school.

“It was a shared governance process where we got some faculty and staff with either an inclination or expertise in this area to guide the process, to help the departments look at their metrics and make decisions,” Osborne said.

The committee met 14 times between Nov. 2019 and Feb. 2020 to draft the process and identify points for departments to consider when evaluating their programs.

Bretz said the committee didn’t tell faculty and departments how to make decisions on their own programs, but rather how to use data to inform their decisions.

“We did not set out to create benchmarks that defined [what a sustainable program was],” Bretz said. “The process instead was built through shared governance to ask faculty to work with a common data set.”

A data-informed process

The data collected through APEIP was far-reaching, covering 133 bachelor’s degrees, 15 co-majors, 66 master’s degrees, 13 doctoral degrees, 13 undergraduate certificates and 24 graduate certificates.

Departments generated workload data, considered university applications by major and identified courses of concern with high rates of students receiving a D or an F or withdrawing (DFW rate).

The APEIP committee evaluated programs in five categories: external demand (job placement), internal demand (growing enrollment), dynamic curriculum (classes with distinctive focus and depth), program outcomes (faculty achievements/experiential learning and career outcomes) and efficient operations (revenue generation and resources used).

Cathy Wagner, professor of creative writing and president of Miami’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), thought the data faculty had to evaluate their programs on was concerning.

“The thing that disturbed me was that there were no questions that had to do with the mission of the university, or with the ideals of a liberal arts education, or anything like that,” Wagner said. “… What they were trying to do is find out where there are sort of expensive courses … that [don't] have very many students.”

To Wagner, the five categories prioritized financial motivations over educational outcomes.

“The way we’re being asked to think about what to sunset, what not, aren’t to do with a sort of sense of our role as an educational institution, our mission as an educational institution, our goal as a liberal arts institution,” Wagner said. “It’s just about money.”

When the process deemed a program unsustainable, that program was recommended for sunset, meaning it would be removed as an option for incoming students to pursue.

Osborne said finances didn’t drive decisions, but that students benefit from decisions that take their tuition dollars into account.

“Students are paying a lot of money to be here, and what we're trying to do is be the best stewards of those resources that we can,” Osborne said. “The taxpayers of Ohio support it, so it's really about stewardship and giving students what they're looking for.”

Denise Taliaferro Baszile, associate dean in the College of Education, Health and Society (EHS), served as interim dean of EHS from January through June of 2021. Before then, her associate dean position involved conversations on how APEIP would affect the college.

She said the data collected didn’t necessarily determine the outcomes for programs.

“Data is something to consider, is something to deliberate on,” Taliaferro Baszile said. “It shouldn't be, in my opinion, that this data equals this decision … We're taking into consideration what we already know about our programs. We're taking into consideration how we manage our resources and our budget and what kind of investments we can and cannot make. To me, all of that has to be on the table.”

Getting results

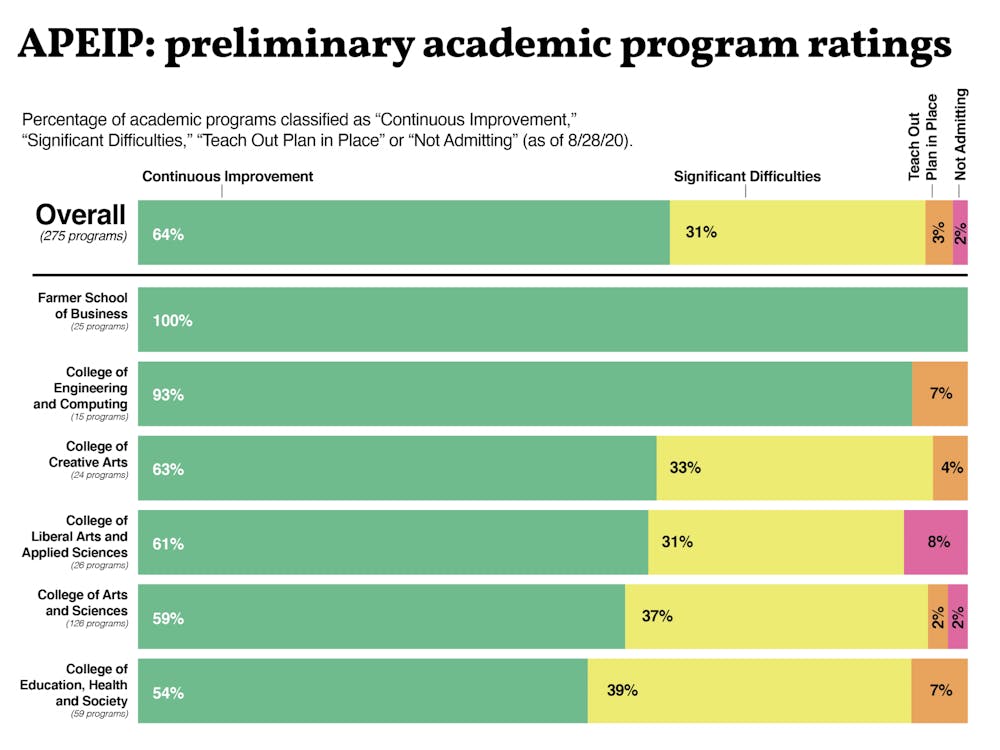

In Sept. 2020, Bretz presented preliminary results to University Senate. Most of the 276 programs evaluated were rated as either “continuous improvement” — programs which had positive student outcomes — or “significant difficulties” — programs with data that suggested difficulty.

In the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), 36.5% of programs were identified as significant difficulties, while 58.7% were continuous improvement. The College of Creative Arts (CCA) identified one third of its majors as significant difficulties, just more than the 31% at the regional campuses’ College of Liberal Arts and Applied Sciences (CLAAS).

In the Farmer School of Business (FSB), 100% of programs were identified as continuous improvement. The College of Engineering and Computing (CEC) listed 93.3% of programs as continuous improvement, with the remaining programs described as “teach out,” meaning current students could finish their degrees but no new students would be admitted.

EHS rated 39% of its programs as significant difficulties, the highest proportion of any academic college.

Taliaferro Baszile said administrators in EHS made an effort to keep faculty involved when reporting initial ratings, though they didn’t always agree on the results.

“Some of the times, we came out with the same kind of assessments, and sometimes our assessments didn't necessarily perfectly align,” Taliaferro Baszile said. “But we were able to have discussions about programs that maybe we needed to sunset.”

Departments then generated action plans and got feedback before receiving final ratings, which broke each preliminary category in two.

Majors with continuous improvement could be listed as either “potential new resources,” meaning the college may allocate additional faculty or funding to the program, or “minor difficulties,” which meant the program wasn’t in danger but had room for slight improvements.

Those with significant difficulties were either recommended for “program restructuring” or labelled a “sunset program.”

Sunset

Chris Makaroff, Dean of CAS, said the Dean’s office gave each program a chance to implement strategies to boost enrollment or restructure to better use resources rather than directly suggesting any programs should sunset.

“As Dean, I could have just said to programs – instead of giving them significant difficulties – I could have said, ‘No, you just need to shut the program down,’” Makaroff said. “I did not do that with any of our programs.”

In some cases, Makaroff and his team responded to departments’ action plans by recommending they sunset certain programs with low enrollment. For struggling bachelor’s degrees like botany, the benchmark was set at 15 graduates per year.

“Neither the BA [bachelor of arts] nor BS [bachelor of science] in Botany have come close to the target thresholds of 50 enrolled students and 15 graduates per program per year,” the CAS response to the biology department’s action plan reads. “ … To avoid sunsetting both or folding Botany into a track within the BA and/or BS Biology programs, the department’s plan must … sunset either the BA or BS in Botany and create a teach-out plan for it.”

Despite the original response to the action plan, both programs were given a final rating of “program restructuring with significant difficulties.” The question of whether to combine or sunset both programs will be readdressed in three years.

“Our goal is to have viable majors that meet the needs of our students, not to specifically shut down majors,” Makaroff wrote in an email to The Miami Student. “But at the same time, I can not justify offering a large number of very low enrollment classes that are required for majors … to graduate.”

Other departments opted to shift their focus away from majors without being told to.

J. Scott Brown, department chair of sociology and gerontology, said his department decided to sunset the gerontology major and instead focus on a minor program to better serve students across campus.

“Students from other [academic] colleges, for example, often … it’s useful for them to have some study in gerontology and aging as an area to be part of their training, leaving Miami,” Brown said. “But if they were in a college other than CAS, that would be difficult to double major in. So focusing on the minors allows us to reach more students, more broadly across campus.”

The undergraduate gerontology major was introduced 20 years ago. Since then, Brown said, it hasn’t had more than about 40 students at once and rarely welcomed more than one or two first-year majors each year.

“It’s definitely a faculty decision,” Brown said. “… That lack of prospects for growth, it wasn’t reaching as many people as we wanted, so we want to focus it more broadly.”

For junior gerontology major Ana Vasconcellos, the email this summer saying the department would stop accepting new undergraduate majors came as a shock.

“It was a little disheartening,” Vasconcellos said. “There's a huge increase in the aging population currently, and even though people choose not to really look at that part of our population, it’s increasing rapidly … In my personal opinion, I would consider it to be a mistake.”

Even though APEIP impacted her own major, Vasconcellos had no idea it existed.

“I knew that [the university was] reviewing gerontology,” Vasconcellos said, “but I didn't know that they were doing [an academic program review] as a whole.”

Tom Peters, sophomore mechanical engineering major and energy co-major, said he hadn’t heard of APEIP, either.

“I don't think most students knew that that even happened,” Peters said. “I haven't heard a single person talking about it.”

Despite this, his own co-major could stop accepting students in as little as three years.

“Why cut [energy] when there's 25 kids really getting something out of it?” Peters said. “I get it, they might have to hire extra staff and stuff. But at the same time, at least for me, this is like the perfect thing I want to help build my resume and have more relevant coursework that I’ll need if I get the job that I want.”

Though programs like energy and gerontology have been put at risk by APEIP, Bretz said the process was meant to be an inventory, not an axe to cut programs.

“The Strategic Plan didn't say, ‘Let's do APEIP every year,’” Bretz said. “It didn't say, ‘Let's get rid of academic programs.’ It was, ‘Let's take a pause, and let's do a comprehensive review of all of our academic programs, and see where we are with regard to student success, meeting employer needs [and] the efficiency of delivering the programs.”

Continuous improvement

Majors defined as continuous improvement also had to generate action plans to move forward.

Andrew Reffett, chair of accountancy in FSB, said his program graduates between 160 and 170 students each year, though undergraduates tend to add accountancy majors later in their college careers, so first-year classes are smaller. Because of this, he said the department planned to focus on recruitment strategies moving forward.

“Our strategy is focused on — at least for the undergraduate program — student recruitment and retention,” Reffett said. “So our efforts to both recruit more students in general, and also recruit more students from historically underrepresented groups.”

Reffett said his department identified two courses with high DFW rates: ACC221 Intro to Financial Accounting and ACC222 Intro to Managerial Accounting. Both are core courses for all FSB students, and Reffett said his department will work to lower the DFW rate.

“The strategies were initially generated at the departmental level and then presented to the dean, and feedback was received,” Reffett said. “I don't know that there were significant adjustments after the dean's office review, but it was somewhat collaborative.”

Even though a majority of CAS majors were identified as continuous improvement, Makaroff said the college overall has been stagnant. As a result, none of the 113 programs that received final ratings in CAS were identified for potential new resources, while 12 were opted to be sunset by departments.

“Because of COVID, we were all in a hiring freeze, and then we're just sort of coming out of it right now,” Makaroff said. “So there are programs that have large numbers of majors, their majors have grown, that will probably eventually get net new resources … but that hasn't happened yet.”

FSB identified 14 of its 23 programs for potential new resources. None are set to be restructured or sunset, though two had already been shut down by the time APEIP began: the BS in interdisciplinary business management and graduate certificate in analytics for professionals.

At the regional campuses, six of the 21 programs evaluated will be sunset, five of which come from the Department of Justice and Community Studies. Seven may get additional resources in the future.

CEC didn’t opt to sunset any of its 13 programs, though the BS in general engineering is already on a teach-out plan. The BS in computer science may see new resources as a result of APEIP.

CCA will sunset four of its 24 programs, including the Master of Music in Music Education and Master of Art in Performance, Theater & Practice. Seven programs were identified for potential new resources.

Of EHS’s 59 evaluated programs, four are already on teach-out plans, and an additional three will be sunset, along with 14 that will be restructured. The college identified 16 programs for potential new resources.

While it can be hard to say goodbye to certain academic programs, Wagner said it’s the reality of working at a university.

“It’s true that there are probably some programs where there isn’t enough demand for a program, and it should go away,” Wagner said. “That can be painful for the faculty who invested time and energy in that program, but it should go away. So we should have a clear and careful and fair process for doing that.”