Miami University professors have spent the past three weeks surveying the beginning of their second year with increased workloads.

A significant reduction in faculty at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic let go of many visiting assistant professors (VAPs) as a money-saving endeavor in anticipation of the pandemic’s financial burden.

This summer, the university’s Board of Trustees allocated $24.6 million to be spent on VAPs in FY22, signaling another change to Miami’s instruction landscape.

The allocation for VAPs coincided with more funds than administrators expected after one year in the pandemic, as well as the enrollment of the largest first-year class in Miami history.

David Creamer, treasurer and senior vice president of business and finance, referenced Provost Jason Osborne as responsible for deciding this budget.

After initially agreeing to an interview, Osborne could not be reached for comment.

VAPs work on one-year contracts that can be renewed for up to five years.

After the university chose not to renew half the VAPs’ contracts, many faculty members dealt with increased teaching loads that left them feeling burnt out during the 2020-2021 academic year.

Charles Moul remembers the “abruptness” of that change.

“So many faculty had to pick up the slack when the university, for liquidity, had to terminate the only employees they could,” Moul said.

Moul, Interim Chair of the Department of Economics, said the two VAPs his department has this semester have already made a noticeable impact.

“That helps,” Moul said. “It helps to provide a portfolio of different educational experiences.”

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Moul said VAPs help manage class sizes, especially of large introductory courses, and relieve strain from the rest of a department.

The same is true at the regional campuses, where Theresa Kulbaga taught five courses each term last year.

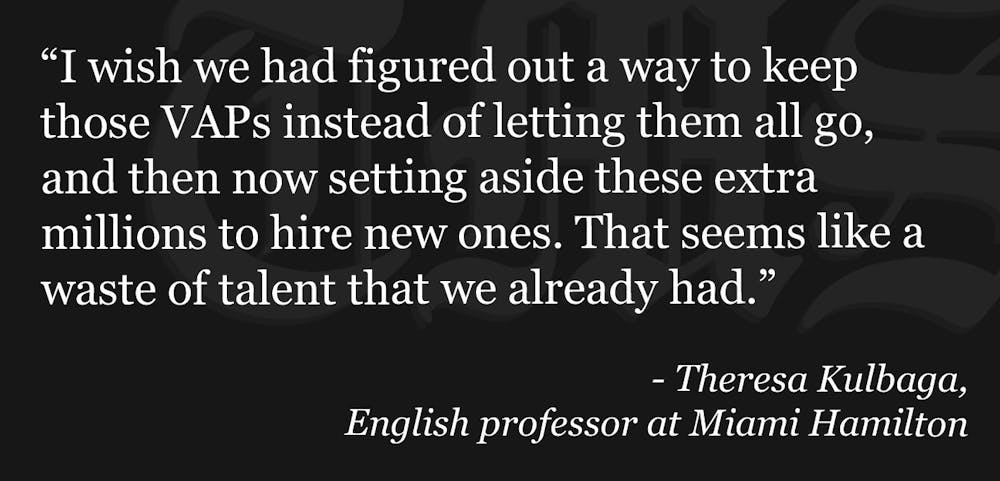

Kulbaga, an English professor at Miami’s Hamilton campus, is happy to be back to her typical course load of three courses one term and four for the other, but wishes the university had found a way to renew VAPs in 2020.

“It seemed like sort of a panic decision,” she said, “or at least a decision that was quickly made without consulting faculty, and I wish that had not happened. I wish we had figured out a way to keep those VAPs instead of letting them all go, and then now setting aside these extra millions to hire new ones. That seems like a waste of talent that we already had.”

Some professors are skeptical about the return of VAPs due to their uneven distribution across departments.

Steven Tuck, professor of classics at Miami for 20 years, doesn’t expect his field to see any relief by allocation of VAPs.

“They’ll hire strategically in areas where they think they can make more money,” Tuck said, “but they’re not going to hire in my area.”

Last fall, Tuck was slated to teach two courses totaling 50 students. Instead, he taught an additional class with 50 students of its own, for a total of three courses and 100 students. He carried that same course load through the spring semester and now faces it again this term.

“On the one hand it’s an unpaid overload,” Tuck said. “But on the other hand, we do care about the students.”

On top of the additional work, Tuck said he spent his summer fulfilling his contractual obligation to research because he couldn’t squeeze it into his schedule during the academic year.

Miami holds a designation as a “Research 2” institution according to the Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education. The designation means the university must maintain a “high” level of research activity. That makes research an important pursuit for most faculty to work on, but with VAPs reduced, remaining professors spent more time teaching and had less for research.

The hit to research is one of many facets of the VAP situation that creative writing professor Cathy Wagner takes issue with.

Wagner, president of Miami’s chapter of the American Association of University Professors (AAUP), said she would prefer to see more secure positions financed at Miami rather than VAP ones.

While job security is a clear benefit to faculty, Wagner said it also works out better for students than hiring VAPs.

“You’re working with somebody, you love their teaching, and they don’t turn out to be around next year to write you a recommendation letter; they’re not even on the Miami email anymore,” Wagner said. “Having such a large percentage of faculty in that position is really harmful.”

Wagner said relying on flexible VAP hirings is a strategy Miami has to use to weather gradually shrinking state funding, which has put money-making more squarely in the middle of the university’s table of goals.

“There’s a focus on revenue as opposed to our educational mission and what we want students to learn,” Wagner said. “Although those faculty were awesome, I don’t think it’s a good idea to talk in terms of, ‘Let’s get back a bunch of VAPs,’ because they’re actually precarious.”