Miami University has taken a new approach to COVID-19 arrival testing by implementing the use of participant cards for all students in addition to the pre-existing method of giving wristbands to on-campus students.

But beyond ensuring that all students returning for the spring semester are given a COVID-19 test, the participation cards are largely useless.

“We needed a method that could help students understand when they could go to class or not go to class,” said Dana Cox, special assistant to the provost for faculty affairs.

Last fall, arrival testing was limited to only on-campus students. After being tested, students were given a red wristband to show their RA that an arrival test had been completed before moving into their dorms. This same practice was implemented this semester, and students only had to wear them until Jan. 25.

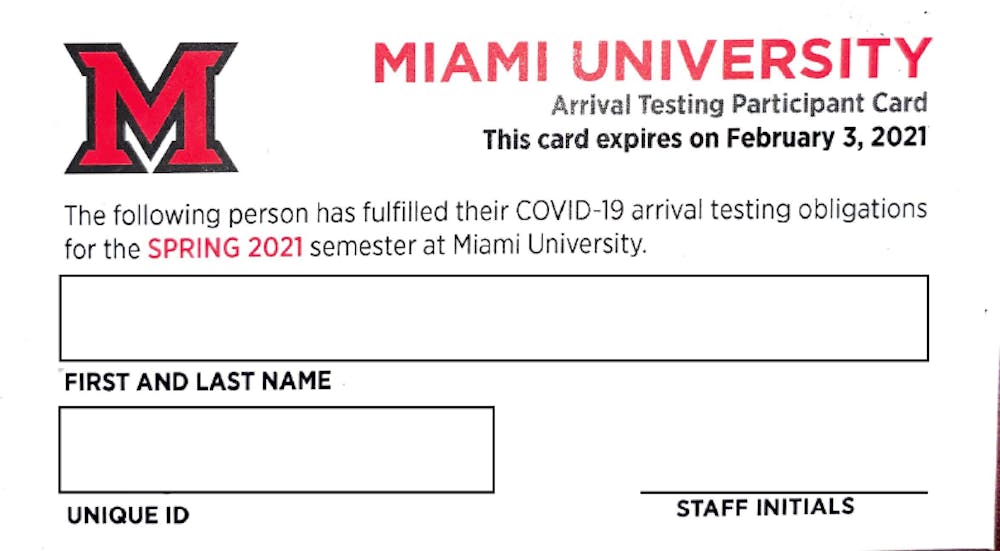

This spring, both on- and off-campus students were required to complete an arrival test before being allowed to attend any in-person classes. Upon completion of arrival testing, all students were given an arrival testing card.

The card includes a student’s name and unique ID, and instructs students to carry it at all times while on campus, as faculty and staff may request to see the card at any time.

“We wanted something that you could just easily stick inside your wallet and forget about until someone asked you to produce it,” Cox said.

Despite the university's good intentions, students are questioning the card’s value.

Sophomore public health major Grace Connors panicked after almost losing her participant card during her first few hours on campus.

After 15 hours of stress, she eventually found the card in her friend’s car, where she had dropped it the day before.

“Then I found out that you really don’t even need the card, because I’ve had two in-person classes this week, and no one’s asked,” Connors said. “At this point, I just feel like it’s a waste of paper.”

Cox said the cards are different from the wristbands because they are intended to let students know where they can go on campus. Students are not supposed to attend in-person class or on-campus activities without the card until Feb. 3.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

“[With] off-campus students, it’s a little more difficult,” Cox said. “There’s no one there to check for wristbands … if we were going to have everyone get tested, we decided that we needed another tool that we could use on campus to kind of help students understand what they could and could not do once they were tested.”

Although students have to carry this card, it does not guarantee that they haven't been exposed to or contracted COVID-19 after their initial test.

"[The card] doesn't indicate the results because if you had tested positive during arrival testing, we would have made sure that you made your way into isolation and you wouldn't be in the classroom anyway," Cox said.

Cox wrote in an email to The Miami Student that the arrival testing cards were “intended to offer a consistent form of verification of participation in the arrival testing program. It is a contract with classmates, instructors, and staff that indicates you're doing what you need to be doing and getting tested when asked."

Although the Healthy Together pledge does indicate a contract between students and administration to comply with testing protocols, the card itself does not indicate or act as such a contract. The card only indicates that students were tested at least once.

Cox said there are no places on campus where showing the participant card is required, but that on-campus employers and professors have the ability to ask students for the card showing proof of their COVID-19 test.

Sophomore strategic communication and interactive media studies double major Adrianna Parker was surprised to find that she was not asked to show her wristband or participant card at all after leaving the testing center on move-in day.

Neither the RA at check in or her supervisor at her job asked for any proof of a COVID-19 test, which she found strange. She still provided her testing card both times, wanting to make a point that she had completed the test and was still following the rules.

“Before I moved in, I thought it was a really good idea to keep track of people … [but] it felt kind of unnecessary,” Parker said. “The test was definitely necessary, but I think that all the extra components … they weren’t used, they were ignored. I think it was a good idea, but the execution was very poor.”