GreenHawks Media is excited to feature a piece from guest writer Allison South on our site. Allison is currently a student in Miami's Environmental Communications class, the class that conceived the idea for and founded GreenHawks Media back in 2010.

By: Allison South

It was already dark outside as I walked through Miami University’s Western Campus, thinking about how cold it was and how much I missed the longer days of summer. As I came around Hillcrest Hall, I warmed up when I saw the fluorescent lights illuminating the red, blue and green pipes inside the building at 341 Western College Drive.

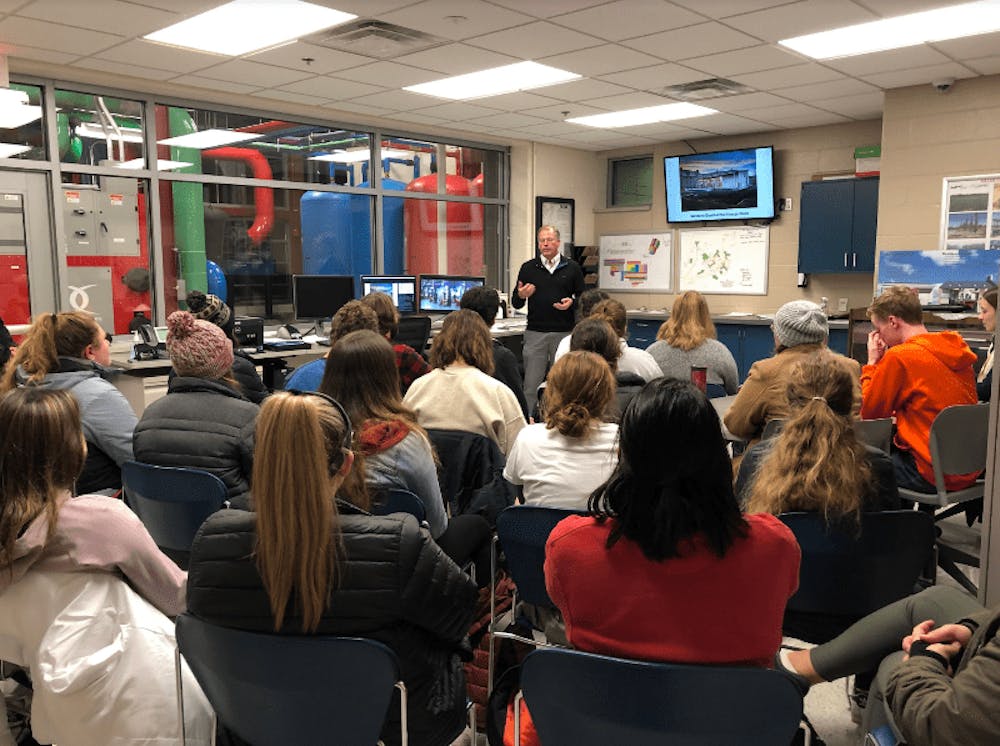

That evening, I was meeting with Doug Hammerle, who was then the Director of Energy Systems at Miami. He had once again agreed to give the Miami University EcoReps a tour of the facility as part of their education on and advocacy for sustainability on campus.

I was more than ready to enter the spacious, mechanical room with tall ceilings as I stepped into the warmth. As Doug and I started to chat about the multitude of times I had received his tour, he offered to let me give the presentation as EcoReps members started to trickle in.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Doug jokingly offered to let me present because I have had the privilege of touring Miami’s geothermal plant nine times during my tenure at Miami through classes and organizations. Each time, I learn something new and am privy to additional questions from the ever-changing groups of students.

On that visit in Oct. 2019, I learned that while many Miami students, faculty and staff appreciate the aesthetics of the ponds between the newly renovated dorms on Western Campus, they do not fully understand their importance. Not only do these ponds provide a natural space for the Miami community, but they also house part of the University’s transition away from steam powered heating and cooling.

Western Campus hosts 690 wells in total underneath the ponds and grass field, most of which go 600 feet straight into the ground. These work with heat pumps in Miami’s geothermal plant, which pumps hot and cool water to several Western Campus buildings, including the renovated residence halls and dining hall nearby.

There is a closed loop of water that circulates through the pipes underground that then transfers through an above-ground heat pump. Due to its high specific heat capacity, the water absorbs heat from the building, runs through the pipes underground to release heat into the surrounding soil, then returns at a lower temperature during the summer. The process works in reverse during the winter when the ground is warmer than the air. This is functional in Ohio due to the state’s seasonality that provides soil that is warmer than the air in the winter, and cooler in the summer.

In addition to learning from Doug about how geothermal heat pumps work, the group also received information about the economic and, most important for the EcoReps, environmental benefits to Miami’s system. In general, geothermal heat pumps are environmentally clean.

While Miami’s steam plant burns fossil fuels to heat and cool buildings, the geothermal plant relies on the naturally-occurring difference between ground and air temperatures. These heat pumps can be 75 percent more efficient than conventional HVAC units, and decreased energy use results in reductions in both cost emissions. Also, this closed loop results in lessened water use, providing cost savings and a sustainable design.

There are also direct aesthetic improvements with a geothermal plant when compared to a steam plant. The ponds and green spaces are a draw for most students, as is the absence of individual heating and cooling units attached to buildings. Beyond these, Doug highlighted the improved safety and the long term cost savings, due to fewer employees being necessary and due to increased energy efficiency, that geothermal plants offer compared to the steam plant.

Miami’s plan to further ‘green’ its campus, coinciding with the signing of the PCLC earlier this fall on Sept. 22, includes transitioning almost all campus buildings off of steam and onto geothermal energy, combined heating and cooling, or hot water heating by 2026. This goal, which Doug Hammerle played an integral part in creating and executing, has progressed for over nine years and continues to be a priority for Miami University.

Students are encouraged to look at Miami’s sustainability website or schedule a tour of the geothermal plant. After nine official visits and a recent tenth one to capture a few outdoor pictures when it was not too dark (and when I was not too cold) I would highly recommend checking out this facility on Western Drive during any season.

All photos courtesy of Allison South