History has shown that, at a university, tension between students and administration is inevitable.

On Sept. 9, Miami University made the controversial decision to bring students back for in-person classes amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Naturally, some students questioned this decision. And just this past Friday, Black Lives Matter protesters took to the streets.

Though this is the most recent subject of disagreement between students and administration, it’s far from the first. In fact, Miami students have a long history of clashing with the higher-ups.

The snowball rebellion: 1848

Student dissent was relatively unheard of in the 19th century. But Miami lays claim to an amusing exception to this rule: the snowball rebellion of 1848.

In 1833, a chapter of the fraternity Alpha Delta Phi, which was founded at Hamilton College a year earlier, was established at Miami. Later, in 1839, Beta Theta Pi was founded at Miami, the first of several Greek organizations founded here.

At the time, the president of the university was Robert Hamilton Bishop, who played a major role in increasing the presence of fraternities on campus. But Bishop’s pro-fraternity perspective was highly controversial, since fraternities were widely considered to be cult-like, and he was dismissed from his position in 1840, largely due to this perspective.

Bishop’s successor, George Junkin — a supporter of slavery who former president Phillip Shriver described as “dictatorial” — urged the Board of Trustees (BoT) to ban “secret societies,” such as fraternities, from campus. The BoT decided to let them stay, but the hostility toward Greek life remained — even when Erasmus McMaster replaced Junkin as president in 1845.

On Jan. 12, 1848, fraternity members rolled a massive snowball and used it to block the door of Old Main, the primary classroom and administrative building on campus, in protest of this anti-fraternity sentiment. A janitor discovered the snowball the following morning, and he notified McMaster.

Later that day, McMaster announced that the men responsible for the prank would be expelled.

Figuring the president couldn’t expel the entire Greek population, all the members of Alpha Delta Phi and Beta Theta Pi got together to expand upon the initial prank. This time, they packed the entire first floor of Old Main with snow.

As it turned out, McMaster was indeed willing to expel the entire Greek population, and Miami’s population dropped from over 200 to just 68 in just a few days.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

This action backfired against McMaster, though, as he was fired for expelling so many students and replaced by a more pro-fraternity president.

Rowan Hall: 1970

During the 1960s, college students across the country became more politically active than ever, and Miami students were no exception.

Most of the protests that came to define the decade were against the Vietnam War, which began in 1955 and didn’t end until 1973.

As the war dragged on, it became increasingly unpopular. By 1970, more than half of Americans believed sending troops into Vietnam was a mistake, according to data from the Pew Research Center.

That year, Miami students decided it was time to make their displeasure toward the war known.

On April 15, hundreds of students marched from Roudebush Hall to Rowan Hall, which is now part of the Armstrong Student Center. At the time, Rowan housed Miami’s ROTC program, which the students viewed as a symbol of the war.

Ted Soares, a former Miami student, led the occupation. He, along with the other protesters, released a list of demands to the administration: stop giving academic credit for ROTC, get ROTC off campus within a year, don’t punish the students participating in the occupation and improve conditions for Black students on campus.

Several members of Miami’s administration — and even the student body president — urged the protestors to leave the building and move their dialogue to a “less disruptive” location, but the students refused.

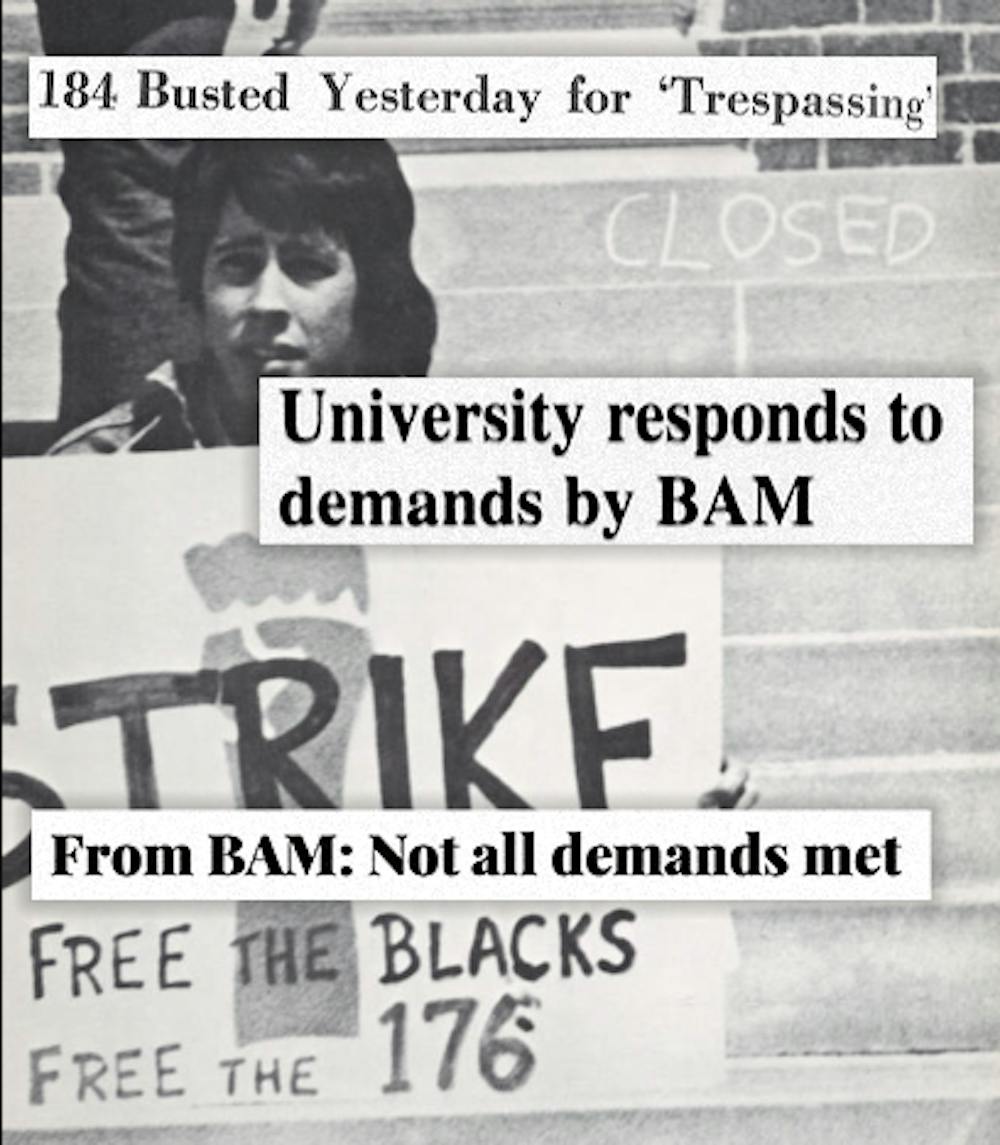

Shortly after, multiple police forces arrived at Rowan and began dragging students out of the building, shooting off tear gas and mace and letting police dogs loose on the protesters. One hundred and eighty-four students were arrested for trespassing, and hundreds more were injured by the tear gas.

Then-president Phillip Shriver defended the police’s actions as “standard operating procedure,” but the student protesters were outraged by the display of force. Many of them called for a strike in the days following the Rowan incident and urged their peers and faculty to skip classes.

In a final act of defiance, the student organizers staged a “flush-in,” in which they flushed toilets repeatedly and turned on all the sinks and showers in their residence halls to drain Oxford’s water supply.

Following the flush-in, the protesters agreed to enter negotiations with administration and return to class.

Despite the injuries and arrests that resulted from the protests, things could have been far worse for Miami’s student demonstrators.

On May 4 of the same year, the Ohio National Guard killed four students and injured nine others at Kent State University during an anti-war protest. It was the first time in United States history that a student was killed during an anti-war demonstration.

Thousands of Miami students marched in honor of the murdered students in the days following the Kent State Massacre, and Shriver decided to close the campus to avoid a similar act of violence occurring in Oxford.

Black student activism: 1970-present

Though the Rowan Hall occupation is generally remembered as an anti-war demonstration, racial justice was also a major goal of the organizers.

Though the Black Student Action Association (BSAA) didn’t formally endorse the protests, several of its members participated, and it released its own list of demands to the administration.

This set of demands — which included increasing the percentage of Black students to 10% by 1974, setting aside graduate assistantships for Black graduate students and recruiting more Black faculty — was the first of several that have been made to the administration by students of color over the years.

The second came in 1997, when a Black first-year student received death threats from a white student via voicemail. In response, a group of Black students formed the Black Action Movement (BAM) and made demands to Miami’s administration.

Some of BAM’s demands were exactly the same as BSAA’s from nearly 30 years earlier, including hiring more Black faculty and increasing the Black student population to 10%. Others included establishing a multicultural center on campus and creating a minority studies program.

The administration agreed to four demands outright: establishing a President’s Council on Multicultural Affairs, completing an institutional plan for diversity, evaluating student support services for underrepresented students and establishing a multicultural center.

The two demands that were repeated from BSAA were not among those that were met.

In 2017, 20 years after the original BAM was disappointed by Miami’s administration, a Miami sophomore used a racial slur in a GroupMe message and later joked about it on Tinder. This incident prompted the formation of a new movement: BAM 2.0.

Like its predecessors, BAM 2.0 demanded Miami increase its proportions of racially diverse students and faculty. Many of its other demands involved increased transparency from the university, such as demanding a report from the associate vice president of institutional diversity, monthly reports on the university’s progress on diversity-related initiatives and a meeting with a group of administrators.

On April 20, 2018, members of BAM 2.0 met with administrators and reported favorably on the statuses on many of the demands. However, in a letter to The Miami Student, the group wrote that the transparency-related demands had not been sufficiently met.

Today, 50 years after BSAA made its initial demands to Miami’s administration, tensions between students of color and the administration are still alive and well.

From the Dear Miami Instagram page to 15 students resigning from the President’s Diversity, Equity and Inclusion task force, students have made it clear that, until the administration steps up its response to their demands, the culture of dissent at Miami will live on.