Hugo Rios-Cordero, a visiting assistant professor (VAP) of film studies and media and culture at Miami University, was ready for next semester. He had all his courses planned out and was set for a promotion to a permanent position at the university.

That is, until he noticed one day that his courses were no longer listed on the schedule.

Now, Rios-Cordero isn’t sure if he’ll have a job in the fall. He likely won’t know until summer, but his lease is up soon. He doesn’t know if he should renew the lease or what plans he can make until he learns if he’ll have a job in the fall.

Higher education is struggling financially due to the novel coronavirus, and Miami is no exception. Recently, the university refunded $27 million in housing, study abroad costs and other fees, according to an email to faculty from President Greg Crawford.

The university is also unsure of the size of the incoming class, so low enrollment numbers could affect the financial situation as well.

Next year, some professors will be expected to teach more classes than they previously did. Because of this, a lot of contingent faculty members aren’t receiving appointments for the 2020-2021 school year. This includes VAPs and instructors, whose contracts are renewed on a yearly basis for up to five years, and visiting faculty (referred to as adjuncts at other institutions), who are paid on a class-by-class basis and typically are not full time. VAPs differ from instructors in that VAPs have the highest possible degree in their field, while instructors do not.

Miami has 5,230 total full- and part-time employees. Eighty-six make more than $200,000 a year.

VAPs make an average of $43,000 per year, according to the university’s most recent salary roster. In comparison, the highest paid employee, head football coach Chuck Martin, made $532,000 in 2019. Crawford, the next highest-salaried, made $520,000 with a $75,000 yearly bonus.

The number of contingent faculty members who will be returning in the fall isn’t finalized, as some may be offered positions based on the size of the incoming class, which will not be clear until after the June 1 decision deadline.

Provost Jason Osborne said many contingent faculty members may not have received appointments even without the coronavirus pandemic.

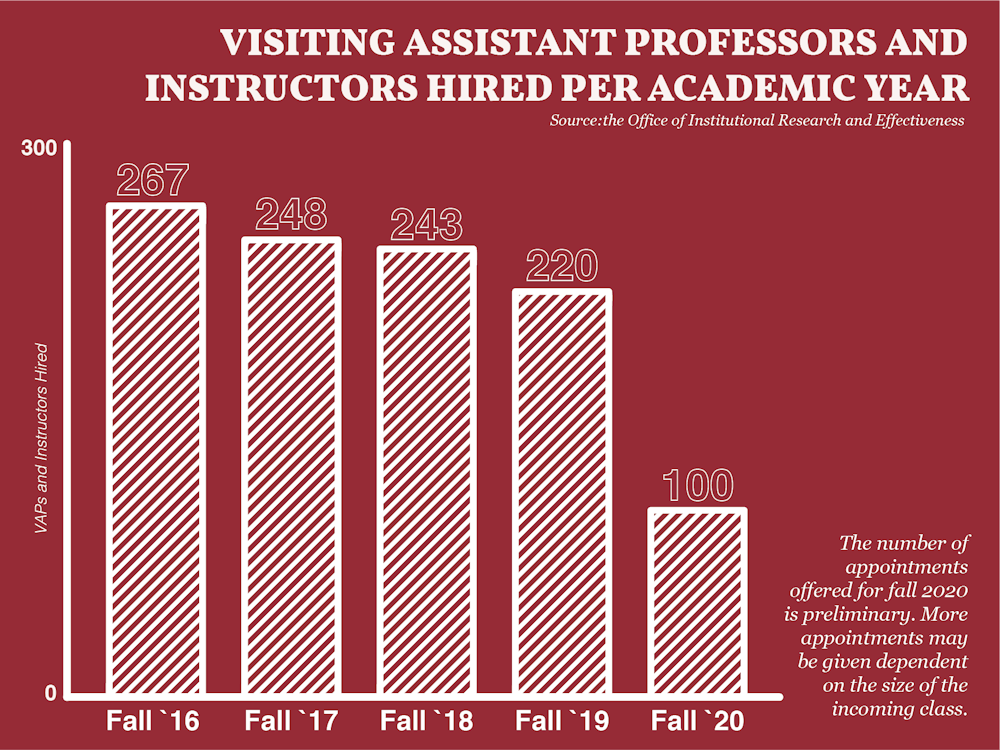

At this time, around 100 full-time contingent faculty members, which includes VAPs and instructors, have had appointments approved for next year. This is a little less than half of those employed for the 2019-2020 school year.

Visiting faculty will also be affected, but it’s unclear how many will receive appointments for the fall semester.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

As VAPs and instructors are hired on yearly contracts, they aren’t being laid off. But many of these people were under the impression they would have a job in the fall.

Typically, VAPs receive a letter every February saying they won’t receive an appointment for the fall. But many of them know the letter is a typical procedure, and that they will likely still receive an appointment.

Beginning in April, many of them are then asked to stay and given classes to teach for the upcoming semester. Appointments continue through the summer, as first-years register for classes and it becomes more apparent where the needs are.

For some like Rios-Cordero, they’re left in a state of uncertainty, unsure if they’ll have a job next year or when they’ll find out.

“Every day, I don’t know what’s going on, and I don’t know what plans I can make,” he said.

Rios-Cordero began as a VAP at Miami in 2015, and he has reached the end of his five-year limit. In February, he was offered a position as a lecturer, a permanent, full-time teaching position, in his department, dependent on approval. He still doesn’t know if he’ll be given that position or not.

Basak Durgun, a VAP of global and intercultural studies, also had reason to believe her position would be renewed for next year. Durgun started at Miami in the fall and heard that although it was a one-year contract, many VAPs are able to stay after that first year.

In February, she received an email from the head of her department saying that he requested her position be renewed and that the dean of the College of Arts and Science agreed. He clarified that nothing was for sure, as the provost makes the final decision, but said it was a good sign that the dean agreed with the renewal.

On Friday, April 10, Durgun received a call saying her position wouldn’t be renewed after all. Out of the nine VAPs in her department, only one has a job at Miami in the fall.

Durgun is worried about the impact this will have on her future career. She started teaching at Miami in fall 2019 directly after graduating from George Mason University with her doctorate degree. Now, she says it’s too late for her to find a teaching job for the fall, as universities have already laid out their schedules and made hiring decisions.

A gap on a resume draws red flags, Durgun said, so she doesn’t know if she’ll ever be able to find another job in academia.

“I think the general public [doesn’t] really realize often that we're emotionally attached to our careers,” Durgun said. “It's not just the job that we go to, but … we form really intense bonds with our students and for me, the biggest heartbreak is that I won't be in the classroom with my students again.”

Rios-Cordero is in a similar situation and has struggled to find a permanent teaching position since graduating with his doctorate degree in 2013. He worked for two years as an adjunct, teaching at Miami, the University of Cincinnati and Xavier University just to make ends meet. In 2015, he was offered a job as a VAP at Miami, and he’s worked in that position for the past five years.

Rios-Cordero said no matter how hard he’s tried to find a permanent teaching position, he hasn’t been offered even one interview. He doesn’t understand why, considering he is a published author and has experience teaching four subjects — film studies, media and culture, Spanish and English.

Dan DiPiero, a VAP of American Studies, had been applying to other jobs before the pandemic began because he knew there was a possibility his contract wouldn’t get renewed. None of those other jobs worked out, though, and he received a phone call on April 10 saying he wouldn’t have a job at Miami next year.

Both Rios-Cordero and DiPiero said they may have to move back in with their parents for a while to save money on rent. All of them will be left without health insurance.

Losing these professors will affect not only their lives but also the lives of their students.

Sophomore Jaycee Streeter said she has formed close relationships with contingent faculty members and that her advisor for her 18-month honors history thesis is a VAP. Now, six months into the project, she will likely have to find a new advisor.

“The whole situation overall is just unfortunate, and these teachers play such an integral part in our education not only in day to day classes but mentoring us over extended periods of time,” Streeter said. “It just seems so sudden and surreal that now I’m off campus, and I probably won’t ever see these professors in person again.”

Michael Loadenthal, a VAP in the Department of Sociology and Gerontology, started The Prosecution Project with a team of undergraduate students. This project is focused on building a database of political violence in the United States with the goal of examining if ethnicity, religion and other factors have an impact on how defendants are prosecuted in a post-9/11 era, Loadenthal said.

About 70 students total have worked on this project since Loadenthal started it four years ago. A team of about 20-25 students is involved each semester, and many students continue with the project for much of their time at Miami.

Since Loadenthal didn’t receive an appointment at Miami in the fall, The Prosecution Project cannot continue at the university. He has received messages from other universities offering to house the project, but current Miami students would likely not be able to continue with the research.

Alexandria Doty, a May 2019 graduate, was on the steering committee for The Prosecution Project and still helps with the project even after graduation.

“Michael was probably the most influential professor while I was there,” Doty said about Loadenthal. “The fact that the university has made the decision to not renew contracts with visiting professors seems to me like they’re prioritizing their budget rather than their students’ education.”

Additional reporting by news editor Briah Lumpkins.