Current Miami University students have faced a variety of struggles due to the spread of the novel coronavirus, such as switching to online classes and having to say goodbye to their friends and return home.

But today’s students aren’t the first to live through a pandemic. There have been four influenza pandemics since the beginning of the 20th century — the most deadly being the Spanish flu of 1918.

Given that online learning wasn’t yet possible, and the U.S. was fighting in World War I while also combating the virus, it’s safe to say Miami’s response to the Spanish flu was a bit different than to the coronavirus.

In the fall of 1918, Miami reached what was then the university’s highest enrollment yet — a whopping 905 students.

This increased enrollment was largely due to the newly-founded Students’ Army Training Corps (SATC), which the U.S. Department of War established in all universities that enrolled more than 100 male students. The SATC trained young college students for combat duty, and dozens of Miami students joined the war effort before it ended in November 1918.

Unfortunately for Miami, this promising semester was turned on its head when the Spanish flu hit Oxford in early October of that same year. Half of the students and a third of the faculty fell ill in just a few days.

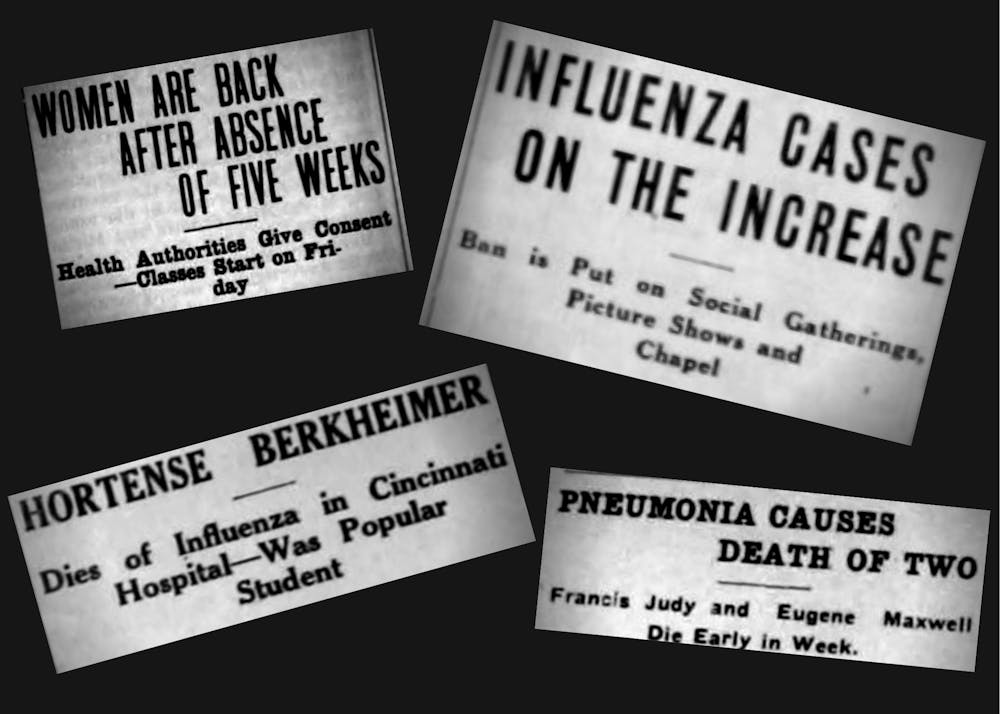

Shortly after the flu arrived in Oxford, Miami sent all its female students home — aside from a few that remained on campus as nurse’s aides — and returned five weeks later when the virus had sufficiently died down. Male students remained on campus to continue their SATC training.

Though Miami never shut down its campus and still held classes, it placed a ban on large gatherings, canceled some sporting events and closed movie theaters and chapels.

Despite Miami’s attempts at social distancing, the flu still spread rapidly, and the hospital in Oxford — which was only equipped to treat 12 patients at a time — quickly became overwhelmed. As a result, Bishop Hall, the girls’ dorm, was turned into a makeshift hospital.

In addition to the underequipped hospital, the spread of the virus exposed an extreme shortage of nurses in Oxford and throughout the country. To correct this issue, Miami introduced a three-month pre-nursing course intended to quickly prepare women for nursing school. The course was modeled after a similar one at Vassar College in New York.

The flu continued to threaten the Miami community until early March of 1919, and a headline in the March 7, 1919, issue of The Miami Student stated the virus was “on the wane” and there were no new cases in Oxford as of that date.

Since Miami remained open and held classes during the Spanish flu pandemic, the current situation — in which campus remains open but classes are held remotely — is unprecedented. But the university does have a couple full closures in its history.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

After the Civil War, Miami’s enrollment steadily declined to 87 students. The main reasons for this decline were twofold: a dramatically reduced enrollment in students from Southern states and the university’s refusal to admit female students.

Due to the financial effects of this low enrollment, Miami closed in 1873 and re-opened in 1885.

Miami also closed for ten days in May 1970 due to protests in response to the Vietnam War. Ohio Governor Jim Rhodes recommended temporary closure of any “disorderly state university,” and Miami President Phillip Shriver elected to close the campus on May 6.

All in all, seven Miami students died from the Spanish flu. Though this number might not seem large, it represents nearly one percent of Miami’s enrollment at the time. For context, if one percent of today’s enrollment was killed by the coronavirus, that would be nearly 200 students.

Brief death notices for students, alumni and well-known locals killed by the flu pepper issues of The Student from 1918 and early 1919.

Many of these notices contained a brief description of personalities or interests — alumna Hortense Berkheimer was described as a “most popular and brilliant student,” and sophomore Mary Jo Gregory was said to be “very interested in teaching.”

Though current Miami students may be frustrated with the changes the university has made in response to the coronavirus, it’s all being done in hopes to protect students in ways that weren’t possible in the age of the Spanish Flu.