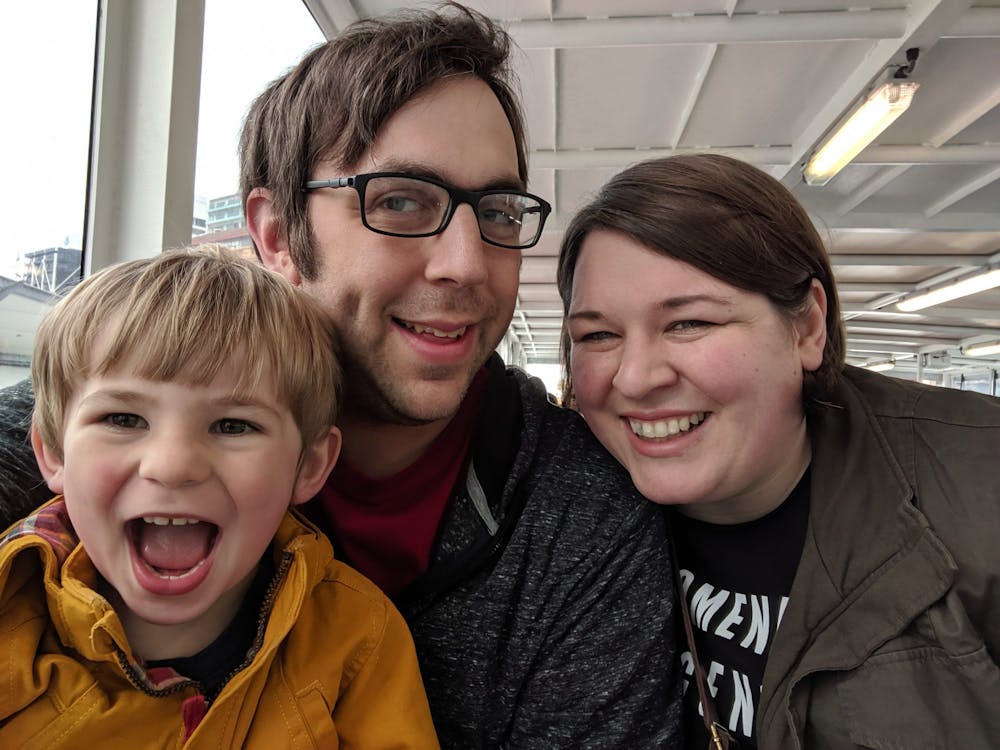

By 9 a.m. in the home of Emily Legg, assistant professors of English and Adam Strantz, assistant professor in Emerging Technology in Business, their three-year-old son, Oliver, is already in full swing.

Each day’s rhythm remains consistent. The day begins with morning meetings for Oliver’s preschool class, then each parent either works with him or prepares for their own classes. There’s a more relaxed lunch period to cook meals together, then some self-designated quiet time, so Legg and Strantz can get work done while Oliver is occupied with a book or iPad.

Later, there’s family time outside — just for the sake of getting out of their house for a while.

Afterward, there are department and committee meetings via WebEx, with either Legg or Strantz participating while the other spends time with Oliver. Dinner follows these meetings, giving way to 30 minutes of precious free time in front of the television before one of them starts on Oliver’s bedtime routine, while the other cleans the dishes and finishes remaining housework.

The day ends with more class preparation — grading, answering emails from students fraught with new questions and planning ahead for Oliver’s next day — before working on their own research, if possible.

For Miami professors with children, like Legg and Strantz, a “regular” day already looks — and feels — worlds different from their old lives under the restrictions of the novel coronavirus stay-at-home order.

“At first, it was just surviving,” Legg said of the immediate transition to remote instruction. “We just did what we needed to do to keep our class functioning. But I knew, too, that while our lives were going through this massive upheaval, our students were going through the same thing. I knew students were moving back home, and for a while there, people were just trying to get through and then figure out what the new normal looked like.”

For Legg and Strantz, a large part of figuring out the new normal while also taking care of a small child has involved delegating responsibilities, with each getting work done for their classes, research and housework, while the other takes care of Oliver.

Their work-filled days have made them prioritize time management and self-care more than ever.

“Time management isn’t just geared toward managing your work time,” Legg said. “You really need to work on managing self-care time. I’ve told my students — and we’ve had to do this, too — to pull up your calendar and schedule time where you’re not thinking about work — where you’re not thinking about schoolwork.”

As a family, Legg, Strantz and Oliver particularly value the time to go outside, even for a little bit, to garden or do yard work.

Legg and Strantz miss particular aspects of pre-pandemic life, such as coffee shops and simply seeing other humans.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

“Our work is motivated by the social atmosphere,” Legg said.

She misses the experience of holding classes and office hours in person and getting to know her students.

Rosemary Pennington, an assistant professor in Miami’s Department of Media Journalism and Film, reflected on the now intertwined balance of work and home life with her 16-year-old daughter.

“We’re both working from home, and I need space — our dining table is a disaster because her books are spread everywhere, my books are spread everywhere,” Pennington said. “It hasn’t been as difficult for us as it probably has been for some of my colleagues who have younger children.”

For Pennington and her daughter, acclimating to the new transition required taking shifts using their communal work space.

“My daughter does a lot of her work in the bedroom, and when she’s working in the dining room, it’s generally at a different time of day than I need to be at the space, because I only work there when I’m writing or actually doing my video classes,” Pennington said.

Pennington described her transition to life under the stay-at-home order as “an extension” of her normal routine. She and her daughter are now around each other constantly.

“Managing home-work life balance and managing relationships is just different, and it’s tricky,” Pennington said.

Pennington finds she’s doing a better job of not overworking now than before the pandemic started. She said staying home has provided her with more structure.

Pennington advises other professors in her position to have patience, both for themselves and for their families.

“Our expectations have to be different,” she said. “They can’t be the same as they were when we started the semester before this became the crisis that it’s become.”

Legg and Strantz echoed Pennington’s sentiment.

“Be kind,” Dr Legg said. “I think that’s the biggest thing. Be kind to yourself, be kind to your kids, be kind to your students and your colleagues. Just don’t be a jerk.”

Legg particularly noted the importance of listening and understanding the emotions of those around her. She also stressed that professors should always reach out for help when they need it rather than isolating themselves.

“Let your colleagues know that others are also struggling,” Legg said. “It’s OK to tell us what challenges you’re facing now.”