When a Miami University student used a racial slur in a GroupMe message in November 2017 and then joked about it in a Tinder conversation a few months later, black students on campus reached a breaking point.

Thus, the Black Action Movement (BAM) 2.0 was born.

Josiah Collins, Vice President of the Black Student Action Association (BSAA) and member of BAM 2.0, said that the movement was started in response to apathy from administration and seeks to benefit all minority groups on campus.

“A group of students came together to let administration know that we were tired of being disrespected on a campus we pay to be on,” Collins wrote in an email to The Miami Student. “The goal wasn’t to just make it better for black students, but for any minority on this campus currently and for those who will be here after us.”

Borrowing its name from the original BAM of 1997, members of the new movement produced a list of demands and deadlines for the administration. Many, but not all, of these demands were met by their respective deadlines.

In 1997, a black first-year student received a voicemail laden with racial slurs and threats. This incident was the catalyst for the original Black Action Movement (BAM) in April 1997.

Many of BAM’s demands were similar to those of BAM 2.0 — increased enrollment and retention of minority students, formation of a new institutional policy for diversity and recruitment of black faculty.

Like BAM 2.0, not all of the original movement’s demands were met. Miami’s administration dismissed certain demands, such as the formation of minority studies programs and increasing minority enrollment to make it proportional to the state population, according to The Miami Student’s summary of the university’s response to the demands.

BAM 2.0 may be the most recent activist movement at Miami, but it’s far from the first.

Miami has a rich history of such movements, which can be traced back 55 years to the Freedom Summer training that took place at the Western College for Women, now part of Miami, in 1964.

Though Miami didn’t directly contribute to the training, the university adopted it as part of its history when it merged with Western in 1974.

In the decades following the Civil War, many black people in the southern United States were unable to register to vote for a number of reasons, including the fact that county officials enforced arbitrary literacy tests and poll taxes designed to make voting impossible for people of color. Even today, laws such as ID regulations disproportionately affect people of color and act as barriers to their political participation.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Freedom Summer sought to remedy this disenfranchisement by sending northern activists — most of them young, white students — into Mississippi to help people of color register to vote.

At Western College, the activists were trained in everything from how to confront angry mobs to how to protect their vital organs while being attacked.

To commemorate Western College for Women’s role in this monumental event, the Humanities Center sponsored the conference “Freedom 55 Mini-Conference: Freedom Summer, Then, Now and the Future” on Nov. 1 and 2, which took place at the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati.

The conference aimed to expose more students to Freedom Summer’s legacy and keep the memory of the movement alive.

A new documentary about the event, which was shown publicly for the first time at the conference, is a step toward achieving this goal. Production of the documentary took six years and was led by Richard Campbell, professor emeritus of journalism.

“I’m very proud of [the film],” Campbell said. “I believe every University 101 class ought to be showing it, just to understand the history of this.”

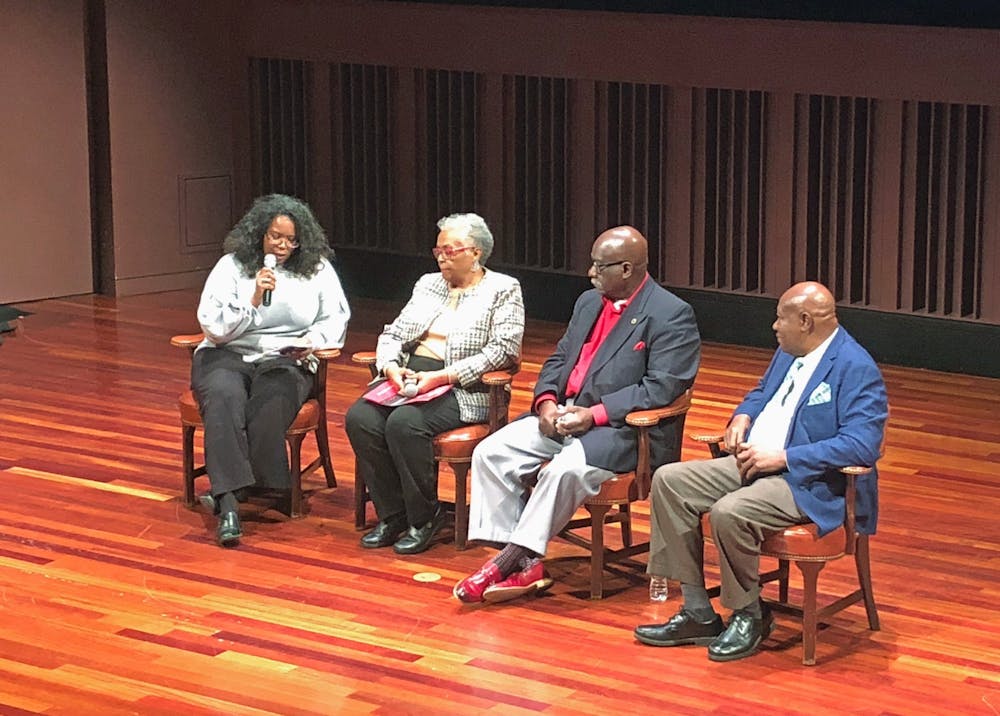

Several of those who participated in Freedom Summer took part in a panel moderated by Miami Professor of History Nishani Frazier and shared their experiences as young activists.

Following the panel, Miami Professor of Global and Intercultural Studies Rodney Coates commented on the significance of the participants’ presence.

“When was the last time you were in a room with three giants — three people who have given so much and received so little?” Coates asked.

Coates also moderated a panel comprised of black Miami alumni who are successful in their careers and involved in social activism.

Yvette Simpson, CEO of Democracy for America, said the opportunities she had at Miami greatly influenced her future success as an activist. She emphasized how crucial it is to know about Miami’s involvement with Freedom Summer.

“This legacy, which Miami should talk about more, is important for folks to know,” Simpson said. “Miami was doing this and was the grounds for these events many decades ago.”

The first major protest at Miami after Freedom Summer was the 1970 occupation of Rowan Hall, now part of the Armstrong Student Center.

On April 15, 1970, hundreds of Miami students occupied the building, which housed the ROTC program, in protest of both the Vietnam war and racial inequality. About 150 students were arrested for trespassing and hundreds more were attacked by Ohio state troopers with tear gas, according to a special report published by The Miami Student the day after the demonstration.

Following the protest, Miami’s Black Student Action Association (BSAA) produced a list of demands to the administration, including increasing enrollment of black students, hiring more black faculty members and absolving those who had been arrested during the Rowan Hall occupation.

Though conditions were gradually improved for students of color, black students still experienced discrimination on campus.

From racist imagery in Miami’s yearbook, Recensio, to racial slurs in GroupMe messages, Miami has a complicated racial history. However, Coates said that there is plenty of evidence that the university has changed for the better in the past fifty years, and will continue this upward trend in the future.

“There were no black folks on this campus fifty years ago, so clearly, things have changed,” he said. “The fact that students are aggressive and actively engaged within this institution means that it is constantly changing.”

One of the main sources of this active engagement is BSAA.

Athena Williams, Political Action Chair of BSAA, said that the organization is currently aiming to keep black students informed and engaged in politics. They’ve accomplished this by educating students on their elected officials, hosting a debate watch party and holding a voter information drive.

“When you live in a democratic representative republic like we do, the only thing that matters is your money and your vote,” Williams said. “Your vote is your power. Your vote is your voice.”

Addressing the attendees of the conference, Coates indicated that the legacy of Freedom Summer must be continued through further activist efforts, both on Miami’s campus and beyond.

“Thank you all for this moment in time; this moment when we reflect upon how we got here,” Coates said. “But as we contemplate this moment, let us not forget that the struggle isn’t over; in fact, it’s just beginning.”

Skyler Black contributed reporting to this story.