As Rosie Ries began to exit the stage after being presented with a prestigious scholarship, any joy she was feeling was immediately overshadowed.

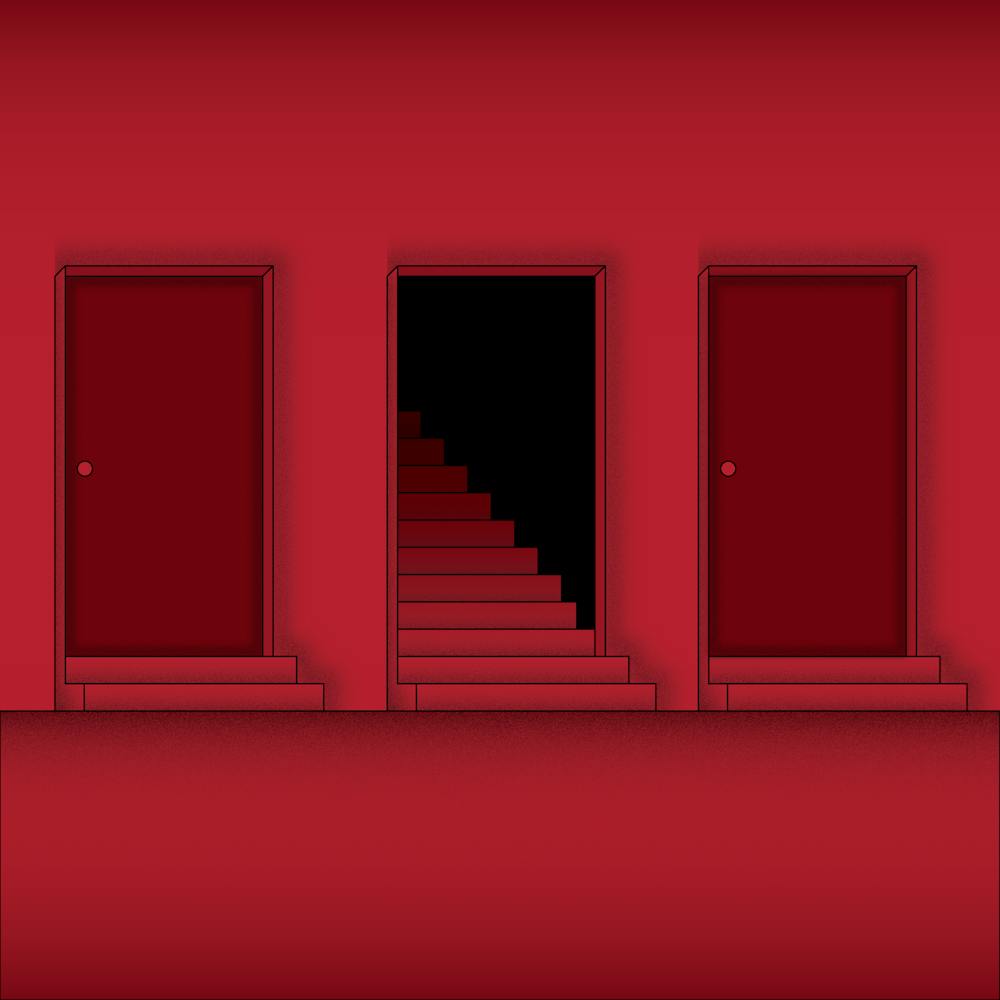

When she reached the stairs, she knew she would have trouble. She didn’t have a choice but to use those stairs, and it almost turned a happy night into an embarrassing incident.

Last month, Ries, the president of the Miami University Students with Disabilities Advisory Council (SDAC), was one of two students to receive the Astronaut Scholarship in Hall Auditorium. This merit-based scholarship is awarded to STEM majors who intend to pursue post-grad research.

Ries has a visual impairment that affects her depth perception. While walking up on stage to accept her award, she found that she had to navigate unmarked wooden stairs that only had a hand railing on one side.

“I almost fell sideways off the stairs, to the point where Dr. [Renate] Crawford … stood up and gave me a hand because she saw that I was unsure where to put my feet,” Ries said.

Ries was surprised this had not been thought through better.

“We’re at a major auditorium, and I’m getting a major award,” she said. “We shouldn’t have this kind of problem.”

While Miami University renovates and updates buildings across campus every year, there are still buildings, both academic and residential, that are not easily accessible for those with disabilities.

According to the interactive campus map, at least two dorms (Thomson Hall and Dodds Hall) have no apparent accessible entrance. Other dorms appear to have no accessible entrances but, in reality, do, indicating that the map has not been updated.

Robert Bell, associate director of planning, architecture and engineering, said Miami’s Physical Facilities department (PFD) does not track these statistics, and could not confirm the number of inaccessible buildings on campus.

“All academic buildings have accessible entrances,” said Dan Darkow, accommodations coordinator for the Miller Center for Student Disability Services. “As a wheelchair user myself, I find this campus to be very accommodating as I navigate campus, and Miami is committed to continual improvement ensuring an accessible experience for all.”

Junior Malone Breland said she faces difficulties while navigating campus. Malone has a non-visible disability in her ankle ligaments, which makes walking or even putting weight on her foot extremely hard at times.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Like Ries, she finds the number of stairs on campus to be a constant source of pain. But Breland said the setbacks a physical disability can cause probably do not even occur to most people.

“I think that’s kind of the thing about being disabled on campus — you can do a lot, but most of it is not easy,” Breland said.

Darkow said approximately 10 percent of Miami students are affiliated with Disability Services, totalling about 2,000 students with reported disabilities. These disabilities include physical disabilities as well as non-visible disabilities, like ADHD, anxiety, depression and migraines.

As listed in the Housing Master Plan, which maps out which buildings will be renovated and when, all residential buildings on campus should be renovated or shuttered by 2030.

The plan, which began in 2009, focuses on remodeling a few dorms each year, taking them out of service during the renovation process.

The oldest dorms were scheduled to be renovated first, with more modern dorms to follow in later years. But renovations have yet to reach many residence halls on campus. According to the Master Housing plan, as of 2019-2020, 15 residential buildings are yet to be updated. Another five were slated to have been taken offline.

“We do have a lot of buildings across campus that are not accessible or [have] limited accessibility,” Bell said.

Thomson Hall, for example, located on Western Campus, has no handicap accessibility. The building entrances only feature steps, and the elevator is used solely for maintenance.

Buildings like Boyd Hall also have poor accessible entrances. It has handicap accessible entrances, but these entrances are located in the back of the building, behind dumpsters or in difficult to access areas.

“Some of the places on campus are sending the message that ‘we don’t really want you here because we don’t want to give you access to the front door,’ and … I don’t think that’s the message we should be sending,” Ries said.

Breland has faced other accessibility issues on campus, like struggling to find a handicap accessible shower. When she requested one and explained that it was crucial for her ability to shower, she found it difficult to convince the university that she truly needed to change dorms. She was eventually given a room on the second floor of her building, far away from the bathroom.

“They did the absolute bare minimum for me, and I felt so uncared for,” Breland said. “Especially, like, to have the Miller Center make me feel like I don’t have the right to accessibility. What do you do after that?”

While recovering from surgery during her sophomore year, Breland returned to her on-campus job as a student manager for one of the dining hall markets. She notified her manager about her surgery and provided a doctor’s note explaining restrictions to her level of physical activity, such as not being allowed to carry heavy objects as she recovered.

Breland said the note sat unread on her manager’s desk for two weeks.

“It didn’t move once, but she said she sent it to her superiors,” Breland said. “So, it was ignored.”

Breland's manager could not be reached for comment.

Miami’s accessibility problems aren’t limited to the lack of wheelchair entrances. Visually impaired students, for example, often also find navigating campus to be difficult.

SDAC has advocated for marked staircases which would allow those who struggle with depth perception to see stairs more clearly. This request, which Ries said has been submitted to PFD multiple times, has never been granted.

“I’ve not heard that myself. Depending on how she made the request, if it was to the Physical Facilities department through the work order system, it should have gotten at least a response,” Bell said.

Bell said PFD doesn’t consider the accessibility of a building until it’s slated to be renovated.

Legally, buildings constructed before the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was passed in 1990 are not required to be handicap accessible unless renovations have been made.

“We do what we can with what we have,'' Darkow said.

When questions arise about accessibility issues, the Miller Center works with the university and is “actively involved in those conversations.”

Bell said that PFD consults with Disability Services while planning new buildings, asking them to review floor plans and highlight any features that may be a problem.

Even when the buildings are renovated, though, some students don’t find the buildings to be fully accessible.

“Large windows next to transparent or open doors can be difficult for the visually impaired to navigate, and running into these windows happens more frequently than they would like,” Ries said.

Ries explained that she understands the university will not become 100 percent accessible overnight.

“I get it. And I get it would cost a lot,” she said. “But it seems like every time they renovate a building, they should think about it more carefully.”