The fear of death is an existential threat that most people can relate to. Countless hours have been spent parsing what that fear means and what we fear most, whether it be in film, in research, or in popular culture.

But are our worries misplaced?

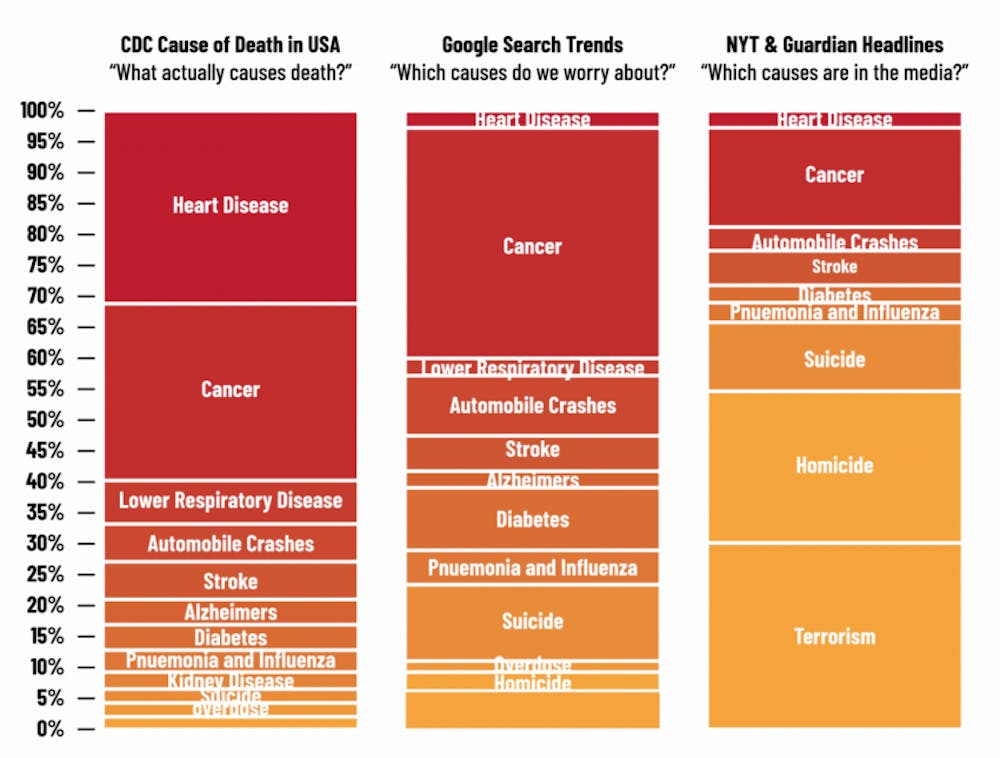

Aaron Penne, a data scientist from Amazon, tweeted an animated graph that showed a disparity between the causes of death that worry us the most as opposed to what is actually killing us.

Penne used data collected by undergraduate researchers at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD). They were interested in looking at the disparity between deaths reported by the media and actual death statistics reported by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Journalism provides the public with accurate information about newsworthy events so that people are up-to-date with everything going on in their communities, government and society. But, there are times when the media affords a disproportionate amount of attention toward terrorism, homicides and suicides while overlooking more deadly health threats like heart disease.

For example, terrorist attacks and homicides significantly disrupt the social fabric of communities, but they only accounted for 0.0078 percent and 0.82 percent, respectively, of deaths in the U.S. between 1999 and 2016.

Over that same period, terrorism and homicides appeared in roughly 55 percent of death-related news coverage by The New York Times and The Guardian.

Heart disease and cancer, on the other hand, are responsible for almost 60 percent of deaths in the United States. And while The Times and Guardian spend nearly 20 percent of their death-related coverage on cancer the number who are worried is 16 percent higher, according to the UCSD study.

Heart disease is relegated to three and a half percent from both papers, but, in reality, it is responsible for the largest percentage of deaths in America -- 33 percent.

These statistics provide a sample of how skewed media's death-related coverage can be in comparison to the ways in which people actually die.

This data is not about how many people die from terrorism or from heart disease, rather the UCSD study says that "the general public sentiment is not well-calibrated with the ways that people actually die."

Simply put: because the media devotes more coverage to abnormal deaths from terrorism, homicides and suicides, Americans believe that more people die from these causes than they actually do.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

What is there to learn from a study like this?

Basically, it's possible to have real data that disproportionately shows events that happen. Distinguishing the difference lies in understanding the context of the data, above all else.