When I was 9 years old, I dressed up as Nancy Drew for Halloween.

I slid on a pair of white stockings under my skirt, slipped a baby pink cardigan over my white shirt and pulled my hair back in a headband. I carried around a plastic magnifying glass and a notebook.

Nancy Drew had been my idol since I got the first six books in the series for Christmas one year. My dad would kneel on the floor next to my bed and he and I would read the books together before I went to sleep.

In the minutes before our Halloween party began, my fourth-grade classroom buzzed with kids sizing up each other's costumes.

"Who are you supposed to be?" one of my friends asked me.

"Nancy Drew," I beamed, holding up my magnifying glass.

Coincidentally, she was also Nancy Drew. A blonde one. A white one.

"Nancy Drew doesn't have black hair," she said.

I knew this beforehand, but I didn't think it mattered. I was unaware at the time that I had to do more than dress the part to dress up as a character for Halloween. I had to look the part, too.

I spent the Halloween party in a less cheery mood, but I don't think my 9-year-old self completely understood why.

That was the first and last year that I went as a specific character for Halloween. Before and after that, I always dressed up as generic characters -- a tennis player, a fairy, one of the three little pigs.

I felt like nonspecific characters were all I had to choose from.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

I wasn't wrong.

Now, 11 years later, I'm not quite as preoccupied with being critiqued for dressing up as a white character.

Now, as a junior in college, I'm more preoccupied with being mistaken for something I'm not.

One morning during my first year at Miami, I put in an order for an omelet at Bell Tower. It was quiet, with only a few students mulling around. I knew I wouldn't have a problem getting a table, so I lingered by the egg counter, waiting for my omelet.

A cook emerged from the back. He didn't see that I had already ordered something. I tend to glance around my surroundings when I have nothing else to do. Maybe it makes me look like I'm lost.

"Welcome," he said to me, slightly louder and more slowly than was necessary. I could sense he thought that I didn't speak English well.

"I'm just waiting for my omelet," I told him. He gave me a quick nod and walked away.

This was a few months into my first year, and one of the first times I realized that here, being Asian can come with the assumption that you are an international student.

And I hate that. And I hate that I hate that.

What is so bad about being an international student?

Why do I get nervous going to new places alone, and in any other situations where I could potentially look lost or like I don't belong?

Why do I feel the need to assert my ability to speak English when I talk to a stranger?

Why do I emphasize the fact that I've lived in the Chicago suburbs for practically my whole life when I tell people that I was born in Korea?

As a junior, I'm still not quite sure.

But what I have come to know is that for a lot of people, my race is the only thing they know about me. And for a lot of them, that's all they feel they need to know.

***

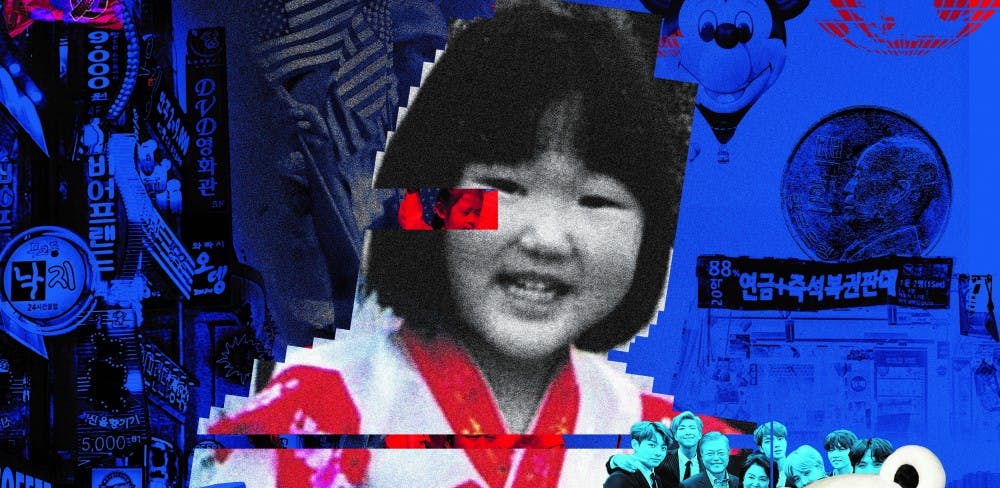

When I was an 8-month-old infant, someone helped me onto a flight to the United States from South Korea. My adoptive parents picked me up at the airport, balloon bouquet in tow, and drove me to their -- now my -- home in the Chicago suburbs.

Growing up, when people asked me about Chicago-style hot dogs or deep dish pizza or whether I was a Sox or Cubs fan, I would shrug. Who cares?

My parents had only moved to Chicago a few years before they adopted me. My dad was born and raised in Long Island, New York, and my mom lived in Malaysia until moving to the United States for college.

But since coming to Miami, I've become a little more outwardly enthusiastic about deep-dish pizza and the Cubs' World Series win in 2016 (their first in 98 years, thanks to the Indians blowing a 3-1 lead).

Chicago culture is what I grew up with. It's something that I can relate to. It's something I can belong to. My family celebrates Christmas like they do in the movies -- Christmas tree in the living room, opening gifts in pajamas, making pancakes for breakfast. None of us have any religious connection to the holiday, but we've celebrated every year.

Then in January or February, my parents hand me a small red envelope filled with money for Chinese New Year.

Growing up, my parents hosted a handful of birthday parties for me, at the pool, the ice rink and in our own backyard, though all my dad had for his childhood birthdays was cake from a box and my mom's family barely acknowledged birthdays at all.

The mom who critiqued crab Rangoon for being inauthentic Chinese food also took me to McDonald's as a child to get Happy Meals.

Whenever we order green beans at our favorite Chinese restaurant back home, my mom teases the way my dad ate green beans growing up -- mushy, cooked to death, from a can. For a while after first moving to the U.S., this was how she thought Americans ate vegetables. To this day, I'm not sure she's been completely convinced otherwise.

I had a reputation in my elementary school classes for being good at math, and I'm still not sure if that was attributed to my skin color or my having taken honors math from the third grade onwards.

I still think it's strange that people wear shoes in their house or don't own a rice cooker.

"White people," I'll say, shaking my head in feigned disapproval whenever my white friends can't handle their spicy food.

There are certain instances where I find myself latching on to and identifying with these Asian stereotypes.

They're small things, but they're things that make me feel like I'm a part of something bigger than myself.

Other times, not so much.

The few unfortunate times that I've been catcalled by someone driving by, the thing they usually call out is my race (not that the comments regarding my ass are any better), as if that's all there is to me.

Back in elementary school, kids at lunch would press their fingers to the outside corners of their eyes and tug back, making their eyes into thin lines.

That's when I became aware that I didn't look like my other classmates.

That's when I learned vaguely what race was and what it meant.

That's when I learned to hate my eyes.

***

Earlier this year, I was assembling a bulletin board for Miami's Confucius Institute for work. A faculty member who was passing by began talking to me in what I assume was Mandarin. He said a handful of sentences before pausing, presumably because it was my turn to chime in.

"Oh, I, uh...only speak English," I said sheepishly. My eight years of Spanish classes would beg to differ, but I'd rather lie than incorrectly guess the language he was speaking.

"Ah, I see," he said, chuckling a bit. "Are you Korean?"

"Yes," I answer.

"You look Korean," he said, smiling. I give him a weak smile in return.

For how many times people have told me this, I still haven't quite figured out how to respond.

Thanks?

At least I can look the part. Maybe that makes up for the fact that I can't speak the part, too.

I've never been met with blatant disapproval or anger for needing to be spoken to in English, but there's usually a sense of discomfort. On my end, there's shame.

I feel like I'm letting someone down, but whether that person is me, the person I'm talking to or Korea as a whole, I'm not sure. I feel like a false advertisement, an imposter, like I mislead people about who I really am, even though I'm not even sure of that myself.

Where do I belong as an Asian American, if not in history classes or television shows?

Where do I belong as someone with black hair, a bridgeless nose and monolids, if not with the Chinese international students?

Where do I belong as someone who grew up in the Chicago suburbs, as a native English speaker, if not with the rest of society?

I want to deviate from the culture that my physical appearance associates me with, but stay true to it at the same time.

By being culturally "white," I feel as though I'm cheating on my Korean-ness -- or, rather, invalidating it, pretending like it doesn't exist, like it doesn't matter.

But by being too Korean, or even simply too "not white," I place myself in a type of social exile from the majority of the peers around me. I feel as though I'm inviting people to stereotype me, to wonder if I'm rich or if I'm going to be a doctor or eat everything with chopsticks.

I'm caught between two worlds, both of which reject me for reasons that are, for the most part, beyond my control. It's confusing. And it's lonely.

***

My mom and I went to see "Crazy Rich Asians" this past summer. We both enjoyed it. There were tears.

After the movie, my mom gushed about this one scene where the main characters are eating street food in Singapore. They showed dishes from her childhood. It reminded her of home. And she was happy that her home was getting some visibility in mainstream pop culture.

For me, the connection was only skin-deep -- seeing people who look like me on a movie screen would have been a big help growing up, and even at 20 years old, I'm overjoyed to see it.

But at 20 years old, I've come to realize that identity entails more than just physical appearance, and there was something missing that the all-Asian cast couldn't give me.

I know how to say "hello" in Korean. I've tried bulgogi and kimchi, two Korean food staples. I can identify the South Korean flag.

The extent of my Korean-ness is comprised of things virtually anyone could do.

I may be Korean by blood and by appearance, but culturally, I'm no more Korean than the average white person.

Just a few days after the release of "Crazy Rich Asians," Netflix released a movie adaptation of the young-adult novel "To All the Boys I've Loved Before." Having read all three books in the series in high school, I was pretty excited to see the charming and admittedly kind of cheesy tale come to life.

But one of my favorite parts of the story is that the main character is a Korean-American girl from a white father and Korean mother who goes to school with students of various races. She isn't defined by being an overachiever or overly quiet, which are two common depictions of Asian characters in the media.

It seems like such a simple concept. But watching that movie was the first time I can remember seeing my reality reflected on screen.

***

I only caught pieces of the Winter Olympics during my sophomore year, but from the beginning, the idea that they were being held in South Korea excited me.

Whenever I saw a name with the Korean flag beside it, I felt some type of loyalty toward them. I don't tend to be super partial when spectating sports (Miami hockey being the exception), but when I happened to see a Korean athlete or team competing, I'd root for them.

My only connection to the Korean athletes is that they represent the country that I was born in. It's somehow both superficial and meaningful in ways that I don't completely understand.

I hope to go back someday. Despite having no memory of the few months I lived there, there's still something about South Korea that screams "home" to me. There's some affinity that I have toward it, the place where I'm from.

I'm not sure when I'll go there. And when I do, I'm not sure if I'll feel like I fit in as a Korean or stand out as an American. Maybe it'll be a bit of both.

I suppose "a bit of both" is just who I am. And maybe that's not such a bad thing.