The OEEO concluded the investigation, but a former student's repeated claims of sexual harassment led to years of doubt and distress.

On Dec. 11, 2002, Jennifer Donnelly, a junior in Miami's Department of Architecture and Interior Design, was getting ready to go home for winter break. She was moving her things from her desk to her car, parked at the loading dock of Alumni Hall, when a professor she knew followed her outside.

As Gerardo Brown-Manrique approached Donnelly, she stepped into what she thought would be a hug goodbye.

Instead, he kissed her on the cheek, then on the mouth.

"He was a professor, and I was an undergraduate," Donnelly said. "I was approached while I was alone on a dark loading dock, and I was kissed on the lips without my consent. I did not want that. I was 20 years old, and I trusted him."

The incident has been a recurring source of frustration and anguish for Donnelly ever since.

Her attempts to resolve the matter -- first in the immediate aftermath, then over the last two years as she applied for an academic position at Miami and considered applying for another -- failed to provide her with any sort of validation or closure.

Ultimately, she said, she forgave Brown-Manrique. But she has not forgiven Miami for how it handled her case.

She believes the university's Office of Equity and Equal Opportunity (OEEO), which handles complaints of sexual harassment against faculty and staff, protected a tenured faculty member at the expense of a powerless female undergraduate.

"I believe the only way out for [the OEEO] was to blame me for my own assault," she said. "I don't want another student to go through that with the OEEO. If that's their policy, that's wrong."

Donnelly was devastated after the incident in 2002. She wondered whether she had led Brown-Manrique on or done something wrong. But, not wanting to tarnish his professional reputation, she decided to let it go. She didn't think the incident would come back.

But it came back the following spring, when other female students told Donnelly Brown-Manrique's behavior had made them uncomfortable.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

It came back in 2010 when her colleagues wanted to know why, since Brown-Manrique's field of study aligned with hers, she'd never taken his classes.

And it came back in 2016, when Donnelly applied for a professorship at Miami.

She tried, again and again, to put it behind her. But like many victims of sexual misconduct, she couldn't.

Donnelly doesn't want it to come back again.

* * *

Donnelly attended Miami from 2000 to 2007. She was an undergraduate until 2004, took a year off to work at an architecture firm, then returned to earn her master's degree in architecture. Donnelly was "an exceptionally fine student," according to her former professor and longtime friend and mentor Sergio Sanabria.

Like many architecture majors, Donnelly spent most of her time working in Alumni Hall. Her desk was situated in front of Brown-Manrique's office.

Donnelly met Brown-Manrique in the fall semester of her junior year. She never took his classes, but the department's amiable, tight-knit atmosphere ensured they ran into one another often. They began quipping that they were "stalking" one another.

"I thought it was all a joke," Donnelly wrote in the report she submitted to the OEEO. "I viewed Mr. Brown-Manrique as a friendly professor who had taken an interest in my future."

When Donnelly moved to leave for the night on Dec. 11, 2002, Brown-Manrique initiated what she assumed would be a brief goodbye hug. But Brown-Manrique continued the hug, and kissed her on the cheek. Then he locked his arms around Donnelly and asked how she liked it.

"It's not a big deal, that's how my grandma kisses me goodbye," Donnelly told Brown-Manrique, in what she felt was an attempt to diffuse the situation so she could leave.

Both Donnelly and Brown-Manrique agree that, after she made the grandma comment, he kissed her on the lips. Brown-Manrique told Donnelly, other architecture professors and the OEEO that it was a "peck," that Donnelly had led him on and that "it wasn't a big deal."

Donnelly remembers it differently.

In the OEEO report, she wrote that she had to "forcibly close her mouth" and, afterwards, "clean his saliva from [her] face."

Donnelly felt the incident "checked all the boxes" indicating that she was sexually harassed. She was standing outside an academic building, she was wearing a winter coat and she was in a committed relationship with her high school boyfriend (who would later become her husband). Neither she nor Brown-Manrique were drunk.

Most importantly, Donnelly had not wanted him to kiss her.

* * *

The day classes resumed in spring 2003, Brown-Manrique put his arm around Donnelly and asked how her break was. Donnelly treated the professor "curtly but with courtesy" for the rest of the semester, she wrote in one of the documents she submitted to the OEEO.

She intended to let the incident go.

But midway through the semester, Donnelly heard other female architecture students discussing behavior from Brown-Manrique that had made them uncomfortable -- joking about wanting to date students, kissing one on the cheek and calling one of them around midnight, asking her to join him Uptown for drinks.

In April 2003, as Donnelly began confiding in close friends about the incident, Brown-Manrique passed Donnelly between Alumni and Irvin Halls and started barking "like a dog" at her. That "bizarre" behavior, Donnelly said, led her to formally report the professor to the OEEO.

Donnelly met with former OEEO director Raquel Dowdy-Cornute, who told her that Brown-Manrique's behavior did not violate Title IX guidelines or Miami policy. According to the OEEO, to qualify as sexual harassment, Donnelly needed to experience more than one incident.

At the time, the OEEO defined sexual harassment as "Unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature," provided that, among other conditions, the behavior "has the purpose or effect of unreasonably interfering with an individual's employment or educational performance or creating an intimidating, hostile, offensive or abusive environment for that individual's employment, education, living environment or participation in a university activity."

In the early 2000s, the OEEO distributed pamphlets about sexual harassment that listed the office's definition of misconduct, a statement from the university president and steps to take for people who had experienced misconduct. It did not mention that, to qualify as sexual harassment, someone had to experience more than one incident.

As Donnelly wrote in a document submitted to the OEEO, "The option of defining non-consensual kissing as sexual misconduct did not come up at all" in her first conversation with them.

The office encouraged Donnelly to voice her concerns to Brown-Manrique herself, so she emailed him at the end of the semester.

"Kissing a student is a completely inappropriate action for someone in your position, and barking at a woman is juvenile and degrading," Donnelly wrote. "Your actions left me ashamed, angry and confused."

Ten days later, Brown-Manrique responded in an email that he was "baffled" by her message.

"I cannot believe that what was strictly a seasonal expression of best wishes should be so interpreted. If you took such, though unintended, as disturbing, I apologize," Brown-Manrique wrote. He wished her a pleasant summer.

* * *

The next semester, in the fall of Donnelly's senior year, she felt driven to report Brown-Manrique to the OEEO again.

She told the OEEO he became generally unpleasant and sometimes downright "hostile" toward her. Donnelly said he regularly slammed his office door when she was within earshot.

Then, in December 2003, Brown-Manrique reviewed Donnelly's final studio project. She wrote in a document submitted to the OEEO that she felt "cheated" by the review, because Brown-Manrique's comments were "bordering on petty, to the point that other critiquers were defending [her] project themselves."

Along with the female student who Brown-Manrique had called at midnight and asked her to come Uptown with him the previous January, Donnelly returned to the OEEO in early 2004. The office told Donnelly and the other student that it had already investigated Brown-Manrique's behavior to the extent of its power.

Donnelly then went to Robert Benson, the architecture department chair at the time, with her concerns. Benson told Donnelly that he had already spoken with Brown-Manrique, who did not feel that he had done anything wrong. Like the OEEO, Benson said, the department had investigated the professor's behavior to the extent of its power.

In February 2004, tired of the lack of administrative response to the situation, Donnelly (and a female friend she brought for moral support) marched into Brown-Manrique's office. She asked why he had kissed her the previous year.

Donnelly wrote that Brown-Manrique acknowledged the power dynamic between them, and that he said her accusations had led him to "shrink from the role of the available and involved professor."

But, Donnelly wrote in the document she submitted to the OEEO, he also told her she needed to be culturally educated and asserted that "It is his right to kiss a student, and he has every intention of doing it again."

* * *

Twelve years later, in fall 2016, Miami's architecture department announced it was hiring a tenure-track professor of interior design. By that point, Donnelly had worked as a professional architect and earned master's degrees from Miami and a university in Pittsburgh, where she was a Ph.D candidate. A Miami professor encouraged her to apply for the job.

Donnelly, along with two other candidates, made it to the final round of the hiring process, and she returned to Oxford in April 2017 to be interviewed.

She had not spoken to Brown-Manrique since confronting him in his office in 2004 and wrote in a document submitted to the OEEO that she had "forgiven" him by that point. Donnelly knew he would be a voting faculty member in the hiring process, but did not feel it appropriate to bring up.

"The last thing I wanted was to be the job candidate who was troubled or traumatized by abuse," Donnelly wrote in the document she submitted to the OEEO.

Donnelly realized early on in the interviewing process Brown-Manrique was not present at any of her required events. The department chair at the time, Mary Rogero, had told her that each faculty member was supposed to have equal face time with each potential hiree.

Concerned that Brown-Manrique's absence would affect her candidacy, Donnelly reached out to her former professor Sergio Sanabria (who was also a voting faculty member) after returning home from the interview. She asked if there was any reason that he knew of why she had not seen Brown-Manrique over the last three days.

Sanabria spoke with Rogero and reported back to Donnelly that Brown-Manrique had been removed from the search, but said she was not allowed to know why until it was over.

After Donnelly learned she was not chosen for the position, Sanabria told her that it was his understanding Brown-Manrique had had a conversation with architecture professor Gulen Cevik about Donnelly in February 2017.

The OEEO spoke with Cevik last spring; she said Brown-Manrique told her about the kiss between him and Donnelly that occurred on Dec. 11, 2002. He told Cevik that "he would not vote for Donnelly even if she was the best candidate," according to an OEEO report, and Cevik reported this conversation to the OEEO. Brown-Manrique was removed from the search.

* * *

When another spot in Miami's architecture department opened up in 2017 -- an architectural historian position -- Donnelly felt she was "expected" to apply, by Miami and by the Pennsylvania university where she now teaches. She said she had not told anyone there about Brown-Manrique.

Wanting clarification about what constituted sexual harassment and retaliation in 2017 before she applied for the new position, Donnelly called the OEEO. She inadvertently opened a Title IX investigation about her situation and, while she said she would have "chosen a different timing" for herself, she was glad it was happening.

Donnelly said that, while the OEEO was initially "diplomatic" in speaking about the 2002 incident, she felt the office became defensive regarding the job search. They told her that they had prevented retaliation by removing Brown-Manrique from the search committee, but Donnelly said they did not seem to consider whether the professor could have affected the process before then.

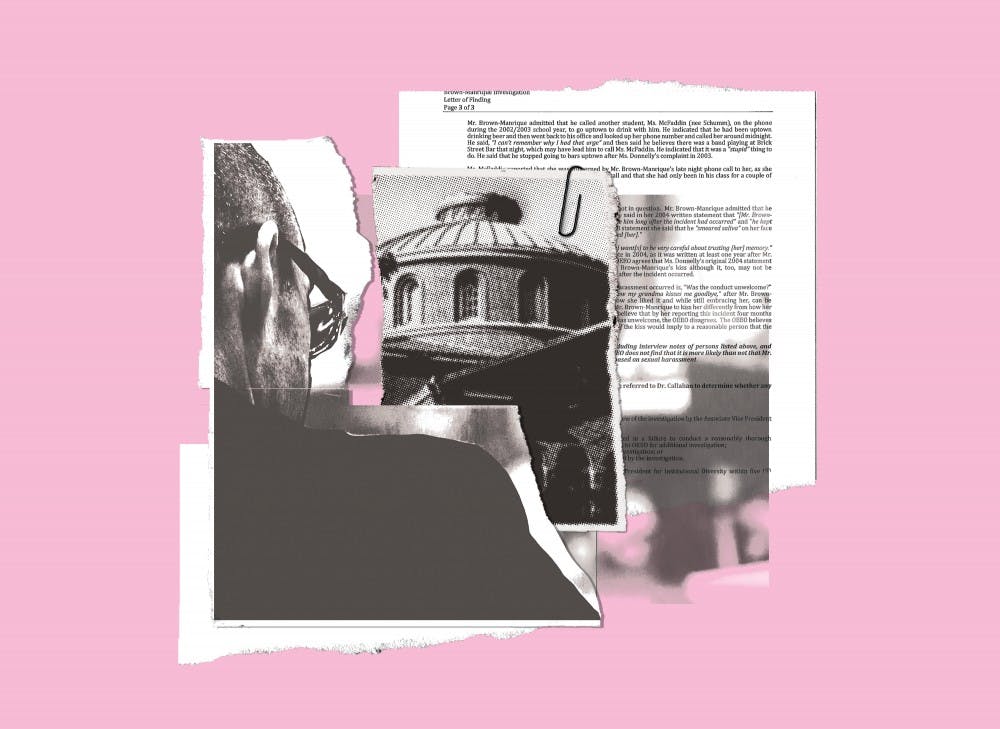

She submitted a 35-page report to the OEEO in February 2018, documenting her concerns. Donnelly wanted the OEEO to investigate whether Brown-Manrique had retaliated against her during her 2004 studio critique, or during or outside of the 2016 conversation with Cevik and whether, under new Title IX rules, the 2002 incident could be considered sexual harassment.

When the OEEO interviewed Sanabria last spring, he told them Donnelly could be flirtatious and that, on Dec. 11, 2002, Brown-Manrique could have "misinterpreted her flirtiness."

But in a letter to the Miami Student on Aug. 20 of this year, Sanabria wrote that the office's failure to include more of his hour-long interview in the report was "tendentious, probably sexist and does not reflect" what he told them.

In their letter of finding, regarding Donnelly's complaint of sexual harassment in 2002, the OEEO cited Sanabria's comment about her "flirtiness." But the letter, Sanabria said, omits other information he gave them last spring, like the fact that Donnelly was an "exceptionally fine student" and that Brown-Manrique is "exuberantly flirtatious."

Sanabria said he began and concluded his interview with the OEEO by telling them he felt they had mishandled Donnelly's case in 2002, and that he feels the OEEO selectively included pieces of his interview to make him appear on their side rather than Donnelly's.

"This could have been resolved easily and straightforwardly, had OEEO acted responsibly," Sanabria said.

* * *

The week the OEEO released its report to Donnelly, which found Brown-Manrique not responsible for sexual harassment or retaliation (or, to use Title IX terminology, that it was "not more likely than not" those offenses had occurred), coincided with the week Donnelly was set to defend her dissertation.

She was granted a two-day extension and filed appeals with the OEEO.

"It didn't sit right with me that the OEEO was willing to blame me for my own trauma," Donnelly said.

Chiefly, Donnelly felt, the office misinterpreted her "grandmother" comment the night of Dec. 11, 2o02 and ignored the power dynamic between her and Brown-Manrique at the time.

"It sounds like we had a romantic encounter gone wrong, and that's absolutely false," Donnelly said. "I've always had the problem of fighting back against that, since the very beginning."

Ronald Scott, Miami's Associate Vice President for Institutional Diversity, finished his reviews of the OEEO's findings on May 23, 2018. The office stood by its earlier decisions. Neither Scott nor any other members of the OEEO, responded to requests for comment for this story, beyond offering a copy of Miami's current sexual harassment policies.

"The conduct of Mr. Brown-Manrique, under the facts and circumstances found by the investigation, was not so pervasive or severe as to create a hostile living or learning environment," Scott wrote in his review. "Consequently, the finding of the OEEO in this matter is upheld."

* * *

The first time Donnelly felt validated about the 2002 experience with Brown-Manrique was while watching the second 2016 presidential debate. The moderator, CNN anchor Anderson Cooper, mentioned Donald Trump's infamous "Access Hollywood" comments about forcibly kissing women. Cooper referred to Trump's actions as "assault."

"I remember feeling a wave of relief, because I had finally heard someone call it that," Donnelly said. "A very prominent male figure calling it that, in a very public way, and I had been told for years, 'It's no big deal.'"

Donnelly attended Miami more than a decade before the #MeToo movement erupted in popular culture. She said the movement is "putting words to things that there weren't words for before."

"It was hard to find my own words in 2004 ... Now, you can read other people's experiences, and you can learn how they narrativized their experiences, and you can think about how your experience was similar or different," Donnelly said. "It creates an ongoing, building narrative, which didn't exist in 2004 and which matters."

She said that, while she's forgiven Brown-Manrique for his behavior toward her, she doesn't think she'll ever be able to forgive the OEEO.

Donnelly would like the office to recognize what happened on Dec. 11, 2002 as sexual harassment. She also said she would like the OEEO to be investigated for how it handles investigations they themselves could be implicated in, and what the office considers consent.

daviskn3@miamioh.edu