aya!

This is the friendly greeting of the myaamiaki, or the Miami people -- the members of the Native American tribe who, before the advancement of European settlers, occupied a large portion of the Great Lakes region and often roamed the land where Miami University now stands. It may be a single small word, but aya represents a language and a culture that has undergone tremendous revival and renewal in the past few decades, thanks in part to Myaamia students at Miami who have embraced their heritage.

In 1846, the Myaamia people were forcibly removed from their homeland after 16 years of resisting the United States government's efforts to displace them through the Indian Removal Act of 1830. Now, the tribe's lands are located in Miami, Okla., and are federally recognized as the Miami Tribe of Oklahoma. Although Miami University, founded in 1809, took its name from the tribe, it wasn't until the 1970s that the tribe and university began to form a relationship.

Today, 31 students of Myaamia descent are enrolled at Miami. For their first three years, they all take a class together on one of three topics: language, ecological perspectives or history and contemporary issues of the tribe. In the fourth year, seniors complete a final project that connects to what they've learned and contributes to the tribe.

Among the tight-knit cohort of Myaamia students are seniors Megan Mooney, Katin Angelo and Zach Roebel. All three are active in the Myaamia community on and off campus, but none of them were born in Oklahoma within the federally recognized tribe. It took coming to Miami for them to understand their heritage and what it meant to them.

Megan's Myaamia blood comes from her father who, although he was aware of his background, never taught Megan anything about it. Megan lived in Indiana near the headquarters of the Miami Nation of Indiana, a Myaamia branch, but she knew nothing of it until a fourth-grade genealogy project brought her family's history to the surface. It was in high school, when her older sister enrolled at Miami and joined the tribe classes, that Megan began to take an interest in her Myaamia history.

"I had no idea," she said. "I grew up in Indiana just thinking I was a white person. I was very ignorant, to say the least."

Katin's grandmother was born and raised in Oklahoma near the tribe, but when local industry stalled, the family relocated to Ohio. Disconnected from his homeland, Katin's father carried the Myaamia bloodline but never learned much about his heritage. Katin's grandmother died when she was young and never had the chance to pass any of her knowledge on to Katin.

Zach grew up in Indiana; his grandfather had strong ties to the tribe, but died when Zach's mother was only 16. Zach would not be born for another 14 years, so he would never know his grandfather. Zach's only source of knowledge about his ancestry was his mother's cousin, who was employed by the tribe and who he rarely saw.

"We just knew the title, we didn't know anything else about it," he said. "Didn't know the language, didn't know any practices, art [or] history about it."

Many might consider Megan, Katin and Zach to be only partly Native American, and many tribes adhere to old federal blood quantum laws which require one to be at least one-fourth or one-sixteenth Native American to be allowed membership. However, the Miami Tribe follows the one-drop rule; one drop of Myaamia blood and documented proof of lineage is all it takes to be a full member of the tribe.

Miami University offers scholarships to members of the Miami Tribe, an opportunity that was too good for Megan, Katin and Zach to pass up. Not to mention that they all had family connections to Oxford: Megan was the second of her siblings to come to Miami, Katin had been preceded by a cousin, and Zach's cousin was the one who encouraged him to apply.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

Nevertheless, Megan, Katin and Zach arrived at their first Myaamia class feeling everything from uncertain to terrified. It seemed like everyone already knew each other. People were speaking in a language they had never heard. They knew next to nothing about the culture they were about to join.

It wasn't an easy transition.

Megan, who for the majority of her life had filled in the "White/Caucasian" bubble on her standardized tests, struggled with changing her view of her identity.

"When I first came here, I felt mostly like an impostor," she said. "I felt like I was just taking advantage of a very thin connection for my own benefit."

Throughout her first year, Katin had trouble feeling like she fit in at Miami.

"I was thinking about leaving [the university]," she said. "Without the tribe, I wouldn't have stayed."

Zach knew no one going in, and didn't know if he would even feel a real connection to his heritage. Maybe the Myaamia classes would become just another thing on the to-do list.

"I didn't know if I was just gonna be sitting in the corner for three years, just minding my own business, just showing up and doing my own work and leaving," he said.

But with time, his fears proved unfounded.

They learned about their history and culture in their classes, and corrected their misconceptions. They went to Winter Gatherings, celebrations each January that bring tribe members from across the country together in Oklahoma. Zach even went his first year, one of only four people to make the trip and the only first-year student to boot.

They met the chief, the elders and many other members of the tribe. People at the Myaamia Center put Katin in touch with members who had gone through the same struggle with belonging as she was.

They were counselors for eewansaapita and saakaciweeta, summer camps in Oklahoma and Indiana for young Myaamia children.

Now, they sport t-shirts and hats bearing the word "Myaamia" with pride. They reach out to new Myaamia first-year students and welcome them as family. And with their final projects, they do their part for the future of their people.

Kaakisitootaawi iilinwiyankwi: Let's preserve our language

In the Myaamia language, Megan Mooney's name is kiilhsoonsa. It means "little sun," "little moon" or "wristwatch," depending on how you use it.

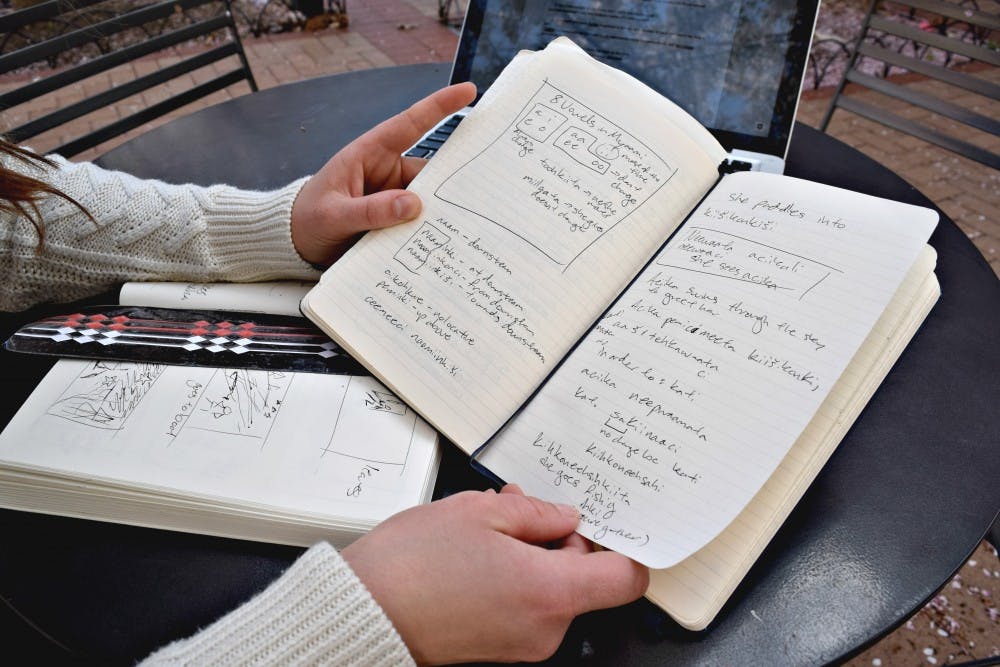

Megan, a creative writing and Spanish double major, has always been fascinated by language and stories. After four years of learning about her heritage as a member of the Miami Tribe -- a heritage her family had all but forgotten about -- she is combining her love of words and Myaamia in her final project: a children's book written entirely in myaamiaataweenki, the Myaamia language. Very few of these exist.

"I think [more Myaamia books] are something we should have," Megan said. "Stories are very big in our culture."

The plot of Megan's story is simple: A little girl feels isolated and thinks that no one understands her. She wants to prove herself, and to do so, she flies up to the moon in a canoe. The tale is not tied to any Myaamia legend or tradition, since Megan feels she is too new to the culture to risk meddling with the tribe's cherished stories.

"[The story] is kind of something weird and stupid, but fun," Megan said.

Although the story is in its early stages, Megan has her process planned out: Draft it in English, then translate it into Myaamia with phonetic pronunciations and a glossary in the back.

Megan did some art and drawing in high school, and so she plans to do all the illustrations herself in order to fit her vision.

"I have a very exact image of what I want it to be," she said.

The translations will be the most time-consuming part because of the nature of the Myaamia language; like many indigenous languages, it is agglutinating, meaning that prepositions are attached to their modifiers and stems are put together. This results in a verb-based language with many long words, such as peehshkikamiiki, which translates to "it is foamy water" and, ultimately, to "beer."

Three decades ago, myaamiaataweenki was dormant. No one had spoken it since about 1960, when the last native speaker died. But in the 1990s, Daryl Baldwin, director of Miami University's Myaamia Center, and linguist David Costa began the long journey of reviving the language. They pored over old manuscripts written by European missionaries and linguists. In reconstructing myaamiaataweenki words, they began lifting the language from yellowed pages and placing it back in the mouths of its people.

As part of this effort, Baldwin and the Myaamia Center organized a trip to Washington, D.C. in 2015 for the Smithsonian's Breath of Life Institute on Indigenous Languages. Megan attended and was able to get involved firsthand with reviving the language by spending time in the Smithsonian's archives.

Since that trip, Megan has felt a strong connection to her tribe, her culture, and her language. She lights up when asked about how the language works, and she regularly attends "language mornings" where Myaamia students get together to practice speaking myaamiaataweenki.

Megan hopes that her book will be distributed to Myaamia families and may even become a part of a "baby kit" given to parents of newborn Myaamia children.

"I just want to write something that little kids and their parents can read together, and hopefully build the language," she said.

Mahkisina ayootaawi miihkintiitaawi: Let's play the moccasin game

Katin Angelo describes the Myaamia creative culture as a web in which every aspect is connected -- language, games, food, songs, storytelling, dances. Losing one part of that heritage puts everything else at risk, too. So, as Megan works on preserving the language, Katin focuses on a traditional tribal game.

Members of the Miami Tribe play many games together. Some are of their own invention, and some are commonplace games given a Myaamia twist, such as euchre played in myaamiaataweenki.

One example of a traditional game is seenseewinki, the plum stone game, which involves tossing colored pieces, traditionally made from plum or peach pits, in a bowl; the combination of colors that land face-up determine how many points the player wins. Another game is played with 101 sticks or straws -- the dealer sorts the sticks into ten piles, and players must guess which pile has more sticks than the others.

Katin's project is about mahkisina meehkintiinki, or the moccasin game.

The moccasin game is a game of chance, played by two teams. Players sit around a mat with four potholder-sized covers -- mahkisinaakna -- decorated with traditional Myaamia ribbonwork. A member of one team hides four marbles -- three white and one black -- one under each of the covers. A member of the other team then flips over the covers with a long stick; if they find the black marble on the second or fourth flip, their team gets points; if they find it on the first or fourth, the other team does.

While playing, everyone speaks myaamiaataweenki.

The game dates back to before the tribe's removal from their ancestral homelands in the Midwest; traditionally, it was played with stones or round lead bullets hidden beneath moccasins, hence its name. It was a gambling game; people would sometimes stake everything they had on the results -- food, clothes, jewelry and more.

"Some people would go home naked," Katin said.

These days, if players gamble, they usually just bet with candy.

Drawing on her life science and chemistry education major, which has helped her learn teaching strategies, Katin will write a lesson plan and create a video to help parents and instructors teach Myaamia children the game and the language that goes along with it. The lesson will also include a brief history of the game and instructions on how to make the ribbonwork mat.

Her project is all about accessibility; Myaamia members live all across the country, but only those in Oklahoma and Indiana or at Miami are close to the happenings of the tribe.

"We have this amazing opportunity here to understand and learn the culture," Katin said, "but how do we get that out to the broader Myaamia community to help them learn and grow, to keep our culture alive?"

Katin's project is her answer to that question. Using modern technology, she's helping keep an age-old native tradition alive.

Pakitahantaawi: Let's play lacrosse

Zach Roebel is focused on a different sort of game, a Native American invention that relies less on chance and more on physical ability: lacrosse.

In high school, Zach played football, ran track and was a male cheerleader, but after pulling a hamstring during track, he decided to give up competitive sports in college. He knew he was better suited sticking to his studies, and double-majored in kinesiology and public health. But Zach's senior project has given him a chance to combine what he's learned with his love of being active by teaching people how to use a Myaamia lacrosse stick.

A traditional stick -- called pakitahaakani -- is completely different from the modern ones typically used to play lacrosse. Made of wood taken from specific parts of the tree, the Myaamia stick features a hoop smaller than a modern stick's, placed off-center to the handle, with a slightly tighter net and a lip on the hoop's edge.

Zach plans to create instructional videos on how to properly handle the traditional stick. Due to the stick's design, players used to using modern sticks would have to re-learn how to scoop, throw and even cradle the lacrosse ball.

The rules of Myaamia lacrosse are mostly the same as those of a modern lacrosse game, although traditionally, it was not nearly as tame.

Lacrosse used to be called "the little brother of war," in part because it was played so ferociously, and in part because it was often used to settle conflicts between tribes, rather than declaring a full war. Sometimes, games would be played in a certain person's honor. Myaamia lacrosse fields could be over a mile long, and games could go for days. Instead of a net, players would have to throw the ball at a sapling, a much smaller target. A knot from a tree trunk was used as the ball. It was thrown hard enough that it could kill a player if it hit them in the head. Despite the size of the field and the sticks, the ball would rarely touch the ground.

In the past century or so, with the advent of modern lacrosse sticks, the Myaamia people gradually stopped making their own sticks. With the limited resources the tribe had after being removed from their land, it was easier and cheaper to buy modern sticks that were more durable. Although the sport itself remained alive and well, the people who knew how to craft traditional lacrosse sticks died and the knowledge was nearly lost.

In recent decades, this knowledge was recovered and the art of making traditional sticks was revived. However, since most tribe members do not know how to use them, they remain, in effect, relics. This is the problem Zach is seeking to rectify.

"In my opinion, there's a difference between bringing the community together with modern-day metal sticks and bringing the community together with traditional wooden sticks that your people used a long time ago," he said. "It just adds more meaning to the game, adds more meaning to our culture."

These days, the playing fields are smaller, the ball is rubber, and often a PVC pipe is used in place of a sapling. But, as is evident in the way the tribe comes together to play and in the bruises Zach sports the day after, it is still very much the fierce and thriving game of his ancestors.

And as a community game, it is not reserved just for tribe members. Myaamia students often bring their non-native friends to compete in matches, and Zach and his peers welcome them.

"I would like to teach it to anyone who would be willing to learn," he said.

A Bright Future

Graduation day looms closer each day for these three seniors, but even though they may leave the Myaamia program within the university, they will never leave the tribe -- nor do they want to.

"One of the big things I've learned about all this is the importance of identity. If I wanted to, I could easily play it off and and play as a Caucasian male for the rest of my life and forget all about this," Zach said. "[Instead, I want to] not only educate everyone around me about what it's like to be a Native American in contemporary society, but also educate my family ... and carry on our traditions for future generations so it doesn't get cut off again."

Megan would love to write more Myaamia books and dreams of being a screenwriter so she can use the platform of TV and film to better represent native people.

"I've talked to some of the tribal council people who are like, 'When we look at you guys, we see a light in our community,'" Katin said.

She plans on using her future career as a teacher to open her students' minds to other cultures and other ways of looking at the world, to get them out of their bubbles just as she popped her own. In the summers,

Katin hopes to come back to camp or do anything else she can to help the Myaamia community continue to grow.

Even as many Native American communities struggle to preserve their traditions in a fast-changing world, the Myaamia grow stronger with each passing year. That's thanks to Megan, Katin and Zach, the students that came before them, the students that will follow them, and many other tribe members for whom the Myaamia culture still lives and breathes.

"If we're not revitalized, then most people would view us as a people of the past," Zach said. "But as we make these strides and continue to move forward into the future, it shows people that our culture and our traditions are not dead. We're still here, and we have some things we would like to share with the world"