A drinking town with a college problem

Lack of home rule stifles city's efforts to control bars

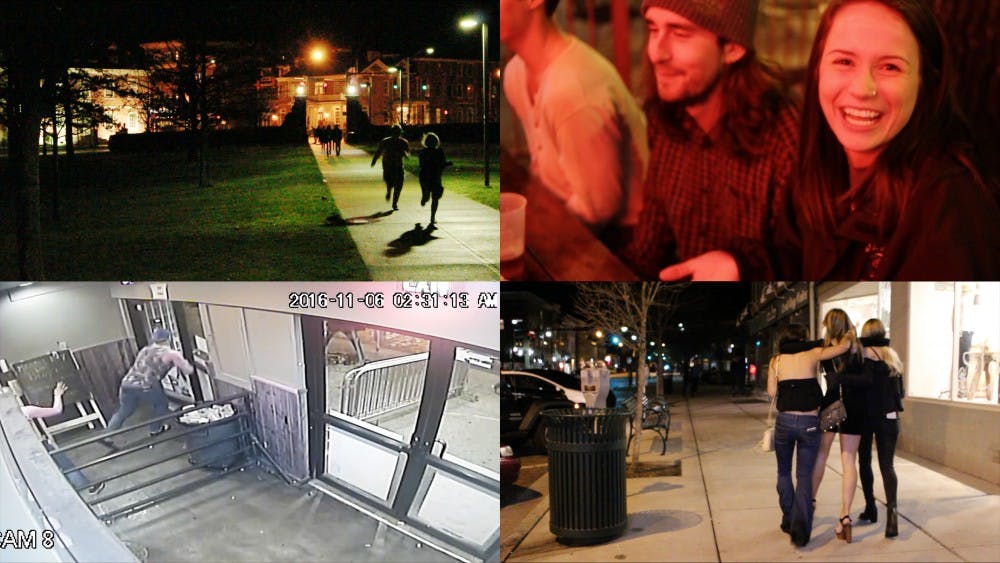

This spring, facing alcohol-related crises on multiple fronts, university administration partnered with officials from the city of Oxford to host several open forums.

The goal of the forums was to confront a drinking culture at Miami University that many have come to see as a public health epidemic and to assure the community that Miami is "committed to doing all that we can to help ensure the well-being of all of our students," as Miami President Gregory Crawford put it.

And yet, even as Miami administrators and Oxford officials talk up their determination to tackle high-risk alcohol consumption, the consensus behind closed doors is clear. In most ways, their hands are tied.

In fact, many Oxford officials concede there has not been an explicit focus on trying to solve the problem at City Hall.

At the heart of the problem is a lack of home rule and a sense of powerlessness in the face of state liquor legislation that the city has little control over.

But economic factors are also at work, and the fear of being seen as anti-business stifles many efforts the city could make to control large, non-restaurant bars, whose competitive drink specials facilitate the high-risk, binging-to-blackout style that defines Miami's drinking culture today.

Oxford's peculiar geography

If you take a stroll up slant walk, the iconic entryway to Miami University (or exit, depending on how you look at it), in one block, you'll find yourself at the corner of High Street and Poplar, home to two of the highest density undergraduate drinking establishments in Oxford.

And if it's a warm Saturday afternoon in spring, the outdoor patio seating at the bars will be jam-packed with jersey-clad students sipping super-sized mixed drinks and guzzling cheap pitchers of light beer.

The proximity of these bars and the loud, alcohol-fueled atmosphere they create is the anecdote most often used to paint a cataclysmic picture of the drinking culture at Miami.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

If you take a bigger town and you put these locations eight blocks from each other, they seem much less consequential, said Mike Curme, the dean of students at Miami University.

But in the peculiar geography of Oxford, they are right across the street from one another.

"On the surface, there is nothing wrong with this," Curme said. "Then you build a community around the Uptown that used to be 50 percent residential, but now has no organic community standards. You see the front yard house parties, the trash, the noise. This attracts attention."

These very visible manifestations of Miami's drinking culture are a problem for administrators because they help form the perceptions students have about alcohol consumption at the university.

In a study conducted by Rose-Marie Ward, a professor at Miami who researches the drinking culture, students were asked two questions: how much do they drink, and how much do they think other students drink? Then, researchers calculated the difference -- what's called a "self-other discrepancy."

Ward's data shows that the average discrepancy at Miami is high. In other words, most students believe their peers drink more than they actually do.

"Students are giving themselves the freedom to drink more because they believe that everyone else drinks an even greater amount," Ward said.

High-visibility house parties have troubled Miami administrators and Oxford officials for years. In 2003, the city adopted litter and noise ordinances -- collectively known as the "nuisance party" ordinances -- to regulate the parties.

But have they worked?

The answer depends on whom you ask. City officials tend to be more optimistic, but Miami administrators are skeptical that the ordinances carry weight.

"We do tend to have more affluent students, so when they get a fine, it's not that big of a concern," said Ward. "I don't think that increasing fines over the last few years has done as much as we thought it would."

A litigious environment

In the spring of 2016, a cadre of Oxford officials, including the city manager, the police chief and the mayor, Kate Rousmaniere, met with the owner of one of the largest and most popular bars in town.

His lawyer in tow, the owner complained that he had a problem with the police. They showed up at his bar every weekend. They weren't nice enough when they arrested underage drinkers. They were bad for business.

Rousmaniere asked the owner, point blank, whether he would stop offering drink specials during the early afternoon hours. He said no.

She asked him why. He gave no answer, so she pushed again. Still, he gave her no answer. A frustrated Rousmaniere asked two more times before the owner turned to her and gave a quick, frank response:

He would not stop the drink specials, he said, because they make him too much money.

That's one of several obstacles to regulating the bars. Efforts to combat high-risk drinking Uptown are often stymied out of a fear of legal retaliation from bar owners.

Then there's the pro-business argument. Whenever one city official talks about regulation, another will say the city's job is to foster business, not restrict it.

As a result, conversations about the drinking culture seldom make it closer to city council than the coffee shop. And in most of her meetings, Rousmaniere said the discussion tends to revolve around how the drinking culture seems to have wheels of its own.

"I wish we could create some local legislation that would give use at least a little authority to control the bars and the drink specials," Rousmaniere said. "But we don't. And we can't. So we end up not really talking about it."

Changing the law so Oxford can restrict drink specials would require sweeping, statewide legislative change. This is because liquor law is controlled at the state level, and Ohio law discourages home rule.

Frustration at the lack of home rule is causing some to brainstorm a more proactive approach: city government can try to regulate behavior more strictly by enforcing ordinances, but can it use other tools at its disposal, like zoning laws, to plan the drinking problem away?

"If we wanted to have a conversation, thinking harder about what type of retail we have Uptown, we could do that," said David Prytherch, a professor at Miami and chair of the planning commission for the city of Oxford. "But the planning conversations have been on one track and the drinking culture conversations have been on another. They don't cross."

It's tough to say what such a planning strategy might look like in Oxford, but the idea of engineering a city's economy away from certain industries or establishments is hardly new. For example, some towns, like Yellow Springs east of Dayton, make the explicit decision to plan against fast food joints or chain restaurants by regulating the hours of the day an establishment can operate.

That takes a certain type of will power, though. And Oxford is more laissez-faire than other towns. It tends to let the marketplace do the work.

It's no secret that a lot of people profit from the student party culture at Miami. There is money to be made. And Oxford can be a litigious environment.

"So, the city is cautious in striking a balance," Prytherch said. "But we're in one of these moments where the status quo is not working. This is a public health crisis and we have a responsibility to look at all possible strategies."

An economic question

Here's how an economist might visualize a solution to the problem: imagine, for a moment, the effects of having only one bar Uptown.

It's a far-fetched idea, but it would get the job done. If there was one bar Uptown, the power of monopoly would allow it to raise prices. It wouldn't need to compete for patrons with day-drinking specials like "Beat the Clock," and it wouldn't turn a blind eye to underage drinking.

Even with a few bars, the effects of limited supply would likely be felt.

But such a scenario is out of reach, at least under the regulations that currently govern drinking in Oxford.

In the state of Ohio, liquor licenses are distributed on a per capita basis. The more people in a municipality, the more liquor licenses the state liquor board makes available. Ohio law allows one on-sight permit for every 2,000 residents.

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city of Oxford has a population estimated to be approximately 22,104 people. That should mean that Oxford has 11 drinking permits available to it. The state liquor board gives it 12. But there aren't just 12 places to get a drink in town.

There are 43.

This is because Oxford is given 12 beer permits, 12 wine permits, 12 liquor permits and 12 "D5" permits. Alan Kyger, the city's economic development director, keeps track of Oxford's liquor licenses. He calls the D5 the "Mac Daddy." It's the permit that gives the owner everything: beer, wine and liquor.

Other grey areas of Ohio liquor law make the number of permits available in Oxford even higher.

Establishments that are physically connected, for example, can share their permits. Think of the doorway that connects The Wood's, aka "New Bar," and Sidebar. They share permits. So do Circle Bar and Steinkeller, which are connected by a passageway. Cru Wine Bar and Patterson's Cafe is another example, and, somehow, Armstrong Student Center and Shriver Center.

But perhaps the largest factor bloating Oxford's liquor permits are Miami University students.

Of the 22,104 people living in Oxford, more than 75 percent -- 16,981 -- are undergraduate students at Miami University. And fewer than half that number are of legal drinking age. Although they only live in the city for four years, the students permanently inflate the number of drinking permits available.

"The model the state uses doesn't always fit a community like Oxford, which has a much younger population base," Kyger said, "though I'm not totally sure, in the long run, what the benefit of having a limit is."

There's a certain population in Oxford that drinks, Kyger said, and if a new bar opens, he's skeptical that it will make the drinking problem worse. The struggle is not the number of permits, it's the way they are used.

"If Oxford Lanes or Phan Shin have liquor permits, is that a bad thing? You can look at the majority of establishments in town and see that they aren't the problem," Kyger said. "The problem are the non-restaurant establishments. They tend to be a problem because you're not going for a meal. You're going for a drink."

An economist by profession, Dean Curme believes the hyperinflation of drinking permits in the relatively small town of Oxford creates intense competition among bar owners to sell large amounts of alcohol at cheap prices during what many consider to be obscene hours of the day.

The resulting drink specials -- such as "Beat the Clock" at Brick Street, "Broken Clock" at The Wood's and "Pitchers" at 45 East -- are of particular concern to Miami administrators and Oxford officials alike, who fear they facilitate high-risk, binging-to-blackout alcohol consumption.

This competition can seem more like a ruinous boomtown economy than the healthy, laissez-faire one that city officials want, and it's caused Curme to formulate his interesting hypothesis:

If a surplus of bars leads to high-risk results, what if there was only one?

Curme would go so far as to conclude that with one bar, no student under the age of 21 would get in, and patrons would be cut off well before they became intoxicated.

"It would be unambiguously conforming to the law and much less likely to have drink specials," Curme said.

"You can contrast that to where we are now."

"Our hands are tied"

For the most part, when a bar applies for a liquor permit, there's not a lot the city of Oxford has control over. The state liquor board processes the application in Columbus and notifies Kyger, who said the city rarely, if ever, tries to deny one.

"So some of our issues are Ohio's liquor laws," Kyger said. "It's the state. The state has their rules and they get plopped down into the community's lap."

This July, the city of Oxford and Miami University will host the second meeting of the Ohio Town and Gown Association, a gathering of Ohio universities and their partner towns.

One goal is to urge members of the Ohio State Liquor Board to lobby for changes that would give college towns more home rule over liquor laws.

The hope among university administrators and city officials is that they can get more power to combat drink specials and the price of alcohol, which up until now, has been the university's primary game plan to combat binge drinking.

"The decision to intentionally binge-drink is an individual choice," Curme said. "I'm falling back on my economics training here. So I think about how we change behavior. Well, we have to increase the cost or reduce the benefit of it."

It makes a lot of sense. If the price of alcohol is higher, it's going to discourage consumption. The idea, named a "Pigouvian" tax after the economist who first suggested it in 1920, is to diminish the ugly consequences of externalities, especially in highly polluting industries.

So with the bars in Oxford, the idea is that if you raise the price of alcohol, students will drink less of it and the damaging effects of high-risk consumption will be diminished.

There is evidence that by eliminating happy hours, you can reduce the human damage associated with high-risk consumption, Ward said. So, if the question is whether totally eliminating day drinking specials like "Beat the Clock" would help, the answer is yes.

"On a lower level, it would deter more students if there weren't drink specials during the day," Ward said.

But higher prices for liquor probably wouldn't deter student drinking any more than fines deter litter and noise, Ward said.

For example, researchers know that if you increase the cost of smoking, it decreases smoking. But what they have also found is that people will linger with their cigarettes and take longer drags.

"So if you increase the price of alcohol, students would just move toward the drinks that have a higher alcohol content, like shots," Ward said. "It's more bang for their buck, and it could be even riskier."

The frustrating reality for Miami administrators is that the best solution to dangerous drinking -- namely, changing attitudes and behavior among students themselves -- lies mostly out of their control.

"As far as reducing the perceived benefit of consuming alcohol, this is largely where I don't know what control we have," Curme said. "Miami students make their decisions off of how they feel the community will view them. And this is where we are challenging students:

"How do you change the culture?"

This story is part of a series on drinking in Oxford. Over the past month and a half, The Student has asked dozens of students, administrators and Oxford residents the same question: "How do you define Miami's drinking culture?" Our coverage, both in print and in the form of a documentary (released on our website April 14) explore the ways in which alcohol is regarded and consumed by Miami students. Our reporting addresses the societal, historical and mental health-related issues that surround drinking in Oxford. Read more of the series here.