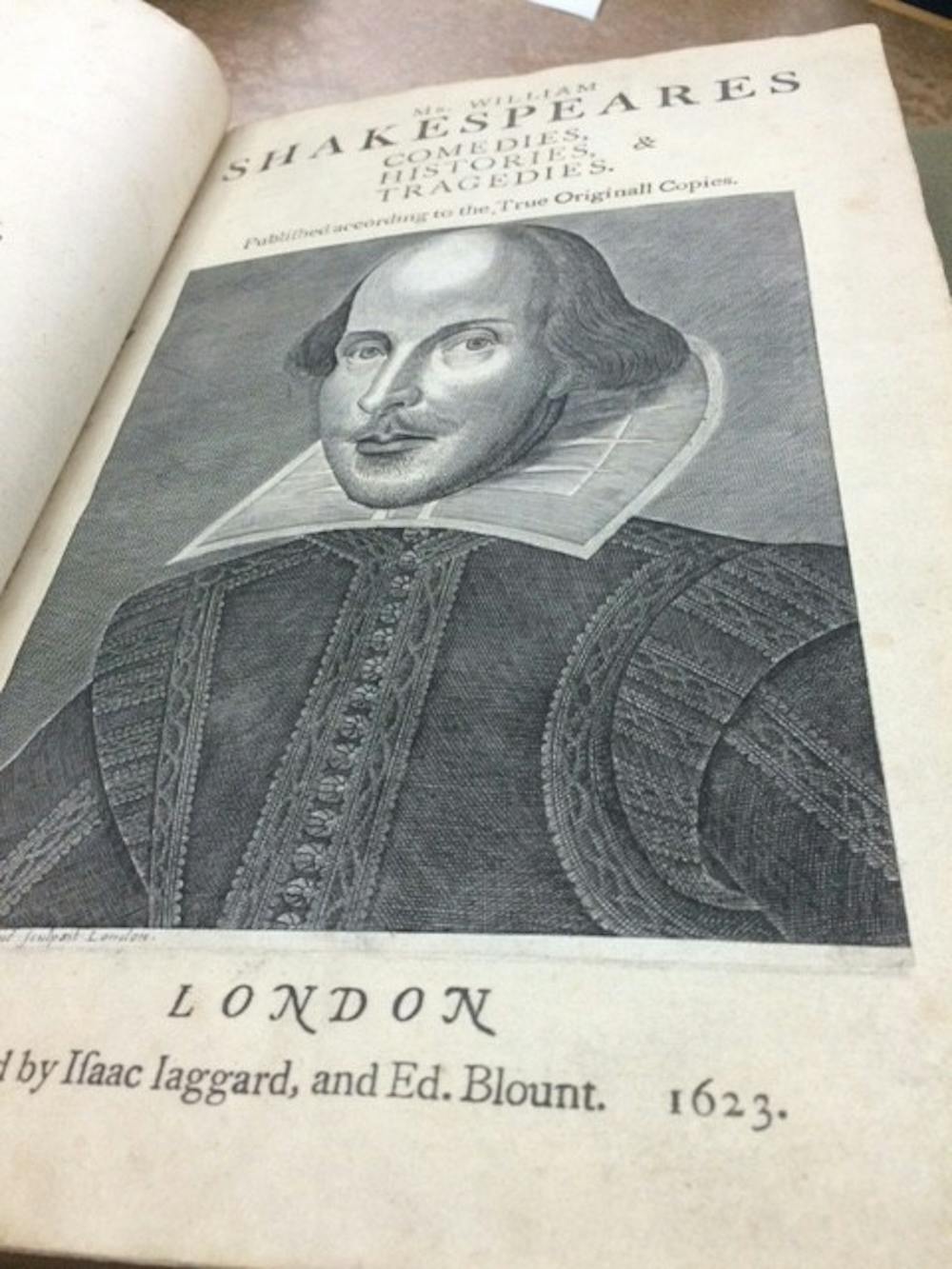

The smell of old books -- faintly vanilla -- wafts from the priceless pages of the first folio of Shakespeare's plays. The old pages creak as a careful hand leafs through the 400-year-old volume.

This is Walter Havighurst Special Collections, which shares the third floor of King Library. It houses all documents, books, artifacts, postcards, etc., that are too rare or valuable to be checked out or circulated within the main library system.

It sits nestled next to a study area, where students silently hunch over their textbooks. A small artifact room -- now displaying nautical history -- opens into a small room lined with offices and tables where visitors can pour over items in the collection.

Visitors to the Special Collections range from professionals and students conducting extended research to curious community members to history classes and individual students who wander up to the third floor. Senior Jessica Scott, student aide in Special Collections, sees students and other users get engrossed in the time-worn items.

"I can see out and you can tell that when they're being helped they get excited about finding information," Scott said.

Many students may not venture so deeply into King Library, and may never discover the treasures that are tucked among the shelves.

"I think that a lot of students don't know about it," Scott said. "I think for students that have never been there it would be cool for them to check it out at one point because there really is some cool stuff," Scott said.

The items range from centuries old books bound in worn leather and gilded pages to ancient artifacts worn smooth by curious fingers. Marcus Ladd, special collections digital librarian and assistant librarian, pulls out a letter written by Abraham Lincoln in on September 10, 1864, less than a year before his assassination. The fingerprint smudged on the yellowed paper, barely visible alongside the elegant handwriting, is Lincoln's own.

"We spend a lot of time here trying to convince people that the stuff we have here is cool," Ladd said.

And some items are more famous than others. Special collections owns a set of all four of Shakespeare's folios, a collection of his works assembled and printed by his friends a few years after his death. Printed in 1623, only 233 copies of the first folio currently exist. To have a set of all four is extremely rare, and is one of the most prized possessions of the collections. According to the Telegraph, a copy of Shakespeare's first folio sold at a British auction for #2.3 million in 2006, or about $3.3 million.

"Most any university you go in this country you're not going to be able to go up and see all four Shakespeare folios," Ladd said.

There also other interesting subcollections within the glass walls. Among the more popular collections is the Bowden postcard collection --nearly half a million postcards chronicling Ohio history and history from far corners of the globe. Postcards from Catholic churches in Mercer County, Ohio, sit alongside cards cataloguing the destruction of WWI from the eyes of the German army. Other collections like Civil War diaries and letters are popular collections among students.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

"I love the postcards," Probst said. "I think there're really interesting, especially the ones that have the letters on them, and some of these are from a hundred years ago."

While most of the items have a clear donor and history, some surprises pop up every once in awhile -- random artifacts that worm their way into special collections, their stories of how they found their way onto the shelves unknown. A few ancient Babylonian clay tablets from about 2300 BC, and an Egyptian tablet from about 1800 BC, were discovered in a shoebox labeled "Ancient artifacts from Hoyt." The tiny clay tablets, despite being nearly 4,000 years old, can be handled by anyone, and fit in the palm of your hand. Nobody knows where they came from or who donated them. However, the tablets are relatively common; a few thousand of them are still in existence.

Old items meet new technology as Ladd digitizes artifacts in the collection so that they can be found online. The work can be tedious, photographing each individual page of a several hundred page book. At the same time, the danger of tearing or damaging a page of a centuries-old book can be terrifying.

"If one of these pages rips I just gotta write my letter at that point," Ladd said, leafing through the Shakespeare folio.

Digitizing the documents and artifacts in the collection has its advantages. A researcher halfway around the world can examine documents online, rather than make the trip to Oxford. Or, if a student has a quick reference question, they don't have to make the trek up three flights of stairs.

It also means the documents and books are handled less, which better preserves centuries old documents.

At the same time, seeing a document on computer screen is one thing, but actually feeling the weight of the book in your hands is a completely different experience.

"It's great that you can sit at home and flip through the first folio--very famous book, printed four hundred years ago--but it's not remotely the same thing as actually touching it and holding it in your hands," Ladd said.