LAWSUIT CONFIRMS FINANCE DEPARTMENT IS AN 'OLD BOYS' CLUB,' PROFESSORS SAY

By Emily Tate and Reis Thebault, Editors-at-Large

Two female professors in the Farmer School of Business (FSB) are suing Miami University, alleging gender discrimination and violation of the Equal Pay Act.

This lawsuit comes after nearly a year of conflict within the finance department and, some say, a decades-old atmosphere that has marginalized female faculty.

"It has been, and, to me, it still remains, a good old boys' club," said Dan Herron, a professor of business legal studies in the finance department and a practicing attorney.

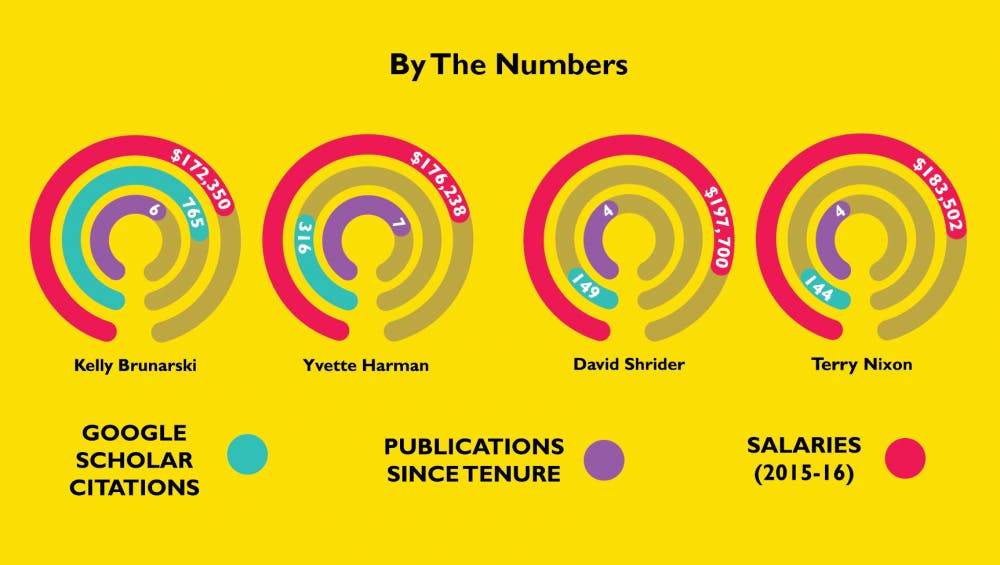

In their initial complaint, filed Feb. 15 in the Southern District Court of Ohio, professors Kelly Brunarski and Yvette Harman compared their credentials to those of two male finance professors. All four were hired and tenured around the same time.

The male professors, David Shrider and Terry Nixon, are paid markedly more than Brunarski and Harman, despite having published less research, the complaint states.

According to the Miami University salary roster for the 2015-16 academic year, Brunarski and Harman are paid about $175,000 each, while the two men are paid an average of 9 percent more.

This pay disparity is not justified by seniority, merit, or any other factors. On the contrary, the complaint argues, Brunarski and Harman have each published more articles in top journals than either Shrider, who is paid nearly $200,000, or Nixon, who makes about $185,000.

Both Shrider and Nixon are part of the department's Promotion and Tenure Committee, which evaluates the progress of junior professors in the department and considers them for tenure. Following a meeting last spring, Dan Herron, then-chair of the committee, complained of gender discrimination by members of the committee.

Herron noticed that Mary Elizabeth Thompson, a tenure-track finance professor, had been subject to an unusual level of scrutiny by her male colleagues on the committee, who characterized her behavior and performance as "uncollegial."

In response, Herron filed a charge of discrimination with Miami's Office of Equity and Equal Opportunity (OEEO). He said the incidents were the latest examples of a longstanding bias against women.

"This department is creating a problem," he said. "We need to stop this. They're going to drive women away from the department. It's an atmosphere that denigrates and does not take women seriously. So, however that manifests itself, it all shows that women are not valued."

In their complaint, Brunarski and Harman used Thompson's troubles to reinforce their own claims, stating that what Thompson had experienced was an extension of the discrimination they had faced since arriving at Miami.

Brunarski joined the Miami finance faculty in 1999, after teaching at the University of Cincinnati and Ohio State University for several years apiece, according to her curriculum vitae. She earned her Ph.D. in finance from The Ohio State University in 1992.

Harman was hired by Miami in 2000 - the same year she earned her Ph.D. in finance from Florida State University - and was tenured in 2006, according to her profile on the FSB website.

Brunarski and Harman are associate professors of finance at Miami.

They, along with Thompson, declined to comment for this story.

After professors within the department made their concerns known to several university administrators - including Provost Phyllis Callahan and FSB Dean Matthew Myers, neither of whom responded to requests for comment - the OEEO began an investigation into the allegations.

However, after stating that her office was too busy to carry out the investigation, OEEO director Kenya Ash requested that an outside party, attorney Juan Jose Perez, examine the claims. Neither Ash nor Perez responded to requests for comment.

University spokesperson Claire Wagner said that Perez conducted a thorough investigation and found no evidence of gender discrimination.

"The university takes allegations of discrimination in any form very seriously," Wagner said in an email. "The independent investigator concluded that there was no evidence to support the faculty claim of gender discrimination."

Herron, however, said that the investigation proves nothing.

"It was a hackjob. [The report contained] false statements of law, false statements of fact. I mean, it was a hackjob," Herron said. "He was unqualified."

Although records show the university paid Perez over $18,000, the complaint states that his investigation at Miami was inadequate.

"The report of the investigation was replete with numerous errors of fact, law and conclusion," the complaint states. "It was unsound in structure, deficient in principle and failed in application."

The university has not yet responded to Brunarski and Harman's lawsuit, but by March 1, Miami had hired Christina L. Corl of Plunkett Cooney law firm in Columbus to serve as its legal representation, according to court documents.

Corl also serves as Special Counsel to the Ohio Attorney General's Office, where she has represented several other Ohio public universities on employment and administrative issues, including discrimination.

In advance of Miami's legal response to the lawsuit, Wagner made it clear how Corl, on behalf of the university, would answer Brunarski and Harman's complaint.

"Miami intends to vigorously defend this lawsuit and denies it has engaged in discrimination of any kind," Wagner said.

Even though Miami is denying the claims, Herron - who has taught business law in the finance department for 24 years - said this is not the first time gender discrimination in the finance department is in the spotlight.

Herron cited the case of former Miami faculty member Anne Lawton, who faced several unwanted sexual advances from a colleague in the finance department during the 1996-1997 school year. Lawton wrote about this experience in an article that appeared in the University of Pennsylvania's Journal of Business Law.

She said her coworker repeatedly groped her and attempted to kiss her on the neck. She reported this harassment using the university's formal resolution process and, eventually, she said that she "won." The harassment stopped. However, she noted, this victory cost her time, money and energy and led to retaliation from within her department. The experience drove her to resign from her job in 2000.

In the article, she wrote that sexual harassment is a systemic, organizational problem.

"Harassment is far more likely to occur in male-dominated workplaces in which women are perceived as interlopers onto male work turf and in workplaces in which harassing workplace conduct is tolerated or condoned," Lawton wrote.

Since Lawton's departure, Herron said, little has changed.

Brunarski and Harman hired Robert Croskery of Croskery Law in Cincinnati to represent them in this case. Croskery is practiced in sexual harassment and employment law. Brunarski and Harman are seeking compensation in excess of $250,000 and demanding that a jury hear their case in a trial."People should be treated fairly and their treatment should not be based on their gender or their race, but rather their intrinsic worth," Croskery said. "Everybody should have an equal opportunity and, if you take away that opportunity by arbitrarily using a suspect classification to say that someone should not get paid as much, then it violates those bedrock and fundamental principles of the Constitution."