The following piece, written by the editorial editors, reflects the majority opinion of the editorial board.

This January, The Miami Student staff participated in a statewide audit to gauge Ohio public universities' compliance with open records laws. By failing to provide a single one of the five public records requested by students, Miami scored lowest for compliance, along with Cleveland State University.

In three instances, student were asked to identify themselves. One was asked if she worked for the student newspaper. Another was told to submit his request in writing.

None of this information is necessary to obtain public records, and to say otherwise is to violate the rights of the person making the request. Furthermore, not a single record request was met with a referral to Miami's Office of General Counsel, as is university protocol. In one case, a student was told the only woman with access to the record in question was in a meeting, and the record was therefore unavailable.

Clearly, there is a disconnect between the existence of Ohio's Open Record Act, Miami's understanding of it and how the university actually carries it out.

Whether the obstructions our student auditors faced were purposeful efforts to shield information or were due purely to ignorance, the fact remains - students were denied records they are entitled to .

All levels of Miami employees need to be aware of what the Ohio Open Record Act necessitates. If the current training is inadequate - as audit results indicate - then more education is needed. Ideally, everyone would be taught how to handle these requests. But if this across-the-board training cannot happen, employees should at least know to whom they should refer requests. Allowing the public access is not an option - it is a right, and a requirement.

As journalists, we at The Miami Student recognize the importance of having public records available. Many of our stories this year, including those concerning fraternity suspensions, sexual assault cases and the presidential search, are products of critically analyzing public documents. Journalism could not function as a fourth estate, a "watchdog" over other entities of power, if government records remained hidden.

While journalists might be the ones who most often utilize their rights to public records, they are not the only ones who benefit. By writing stories with information from these documents, journalists educate the public on issues they would not otherwise know about.

When we ask Miami for public records, we are not asking for their information - the records don't belong to them. The records belong to the public. They belong to us.

Because Miami is a public institution, funded by taxpayers' money, citizens are entitled to know how that money is being spent. They have the right to know how the university is making decisions and how it conducts itself. And they have the right to be given this information in full, in a timely manner upon request, for any reason and without further questions or any intimidation tactics employed.

This week marks the 50th anniversary of the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), a federal law allowing Americans access to government information. It is also Sunshine Week, a "national initiative to promote a dialogue about the importance of open government and freedom of information," according to Sunshine Week's website.

It is important this week -- and every week - not only to celebrate the right we have to access information, but also to fight to ensure it is being upheld. We must challenge those who try to infringe on this right, or limit our access to information we are entitled to have.

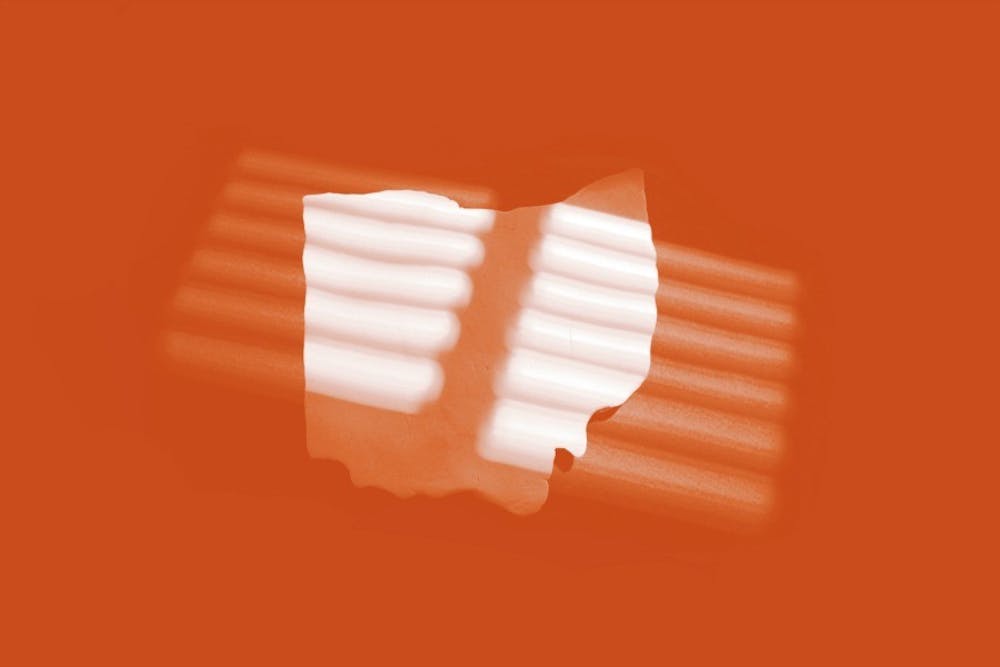

Open records laws are nicknamed "Sunshine Laws," because they are intended to shine light into dark, otherwise concealed areas and see what might be hidden. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis said, "If the broad light of day could be let in upon men's actions, it would purify them as the sun disinfects."

Unfortunately, Miami's poor performance on this year's audit makes us wonder: what is the university trying to hide?

We have learned first-hand this year that transparency is not Miami's strongsuit. Failure to comply with the five records requests made this January is indicative of a larger, more problematic trend.

Admittedly, only one school statewide had perfect compliance. While Miami's results are the most severe, they are not a rarity. This highlights a need for increased training on the handling of public records at universities across the state. Hopefully the disappointing results of this year's survey will motivate state institutions to reevaluate their behavior and make the necessary improvements.