"War is hell. But don't blame the warriors," he says, readjusting his cap that reads, "Vietnam Veteran."

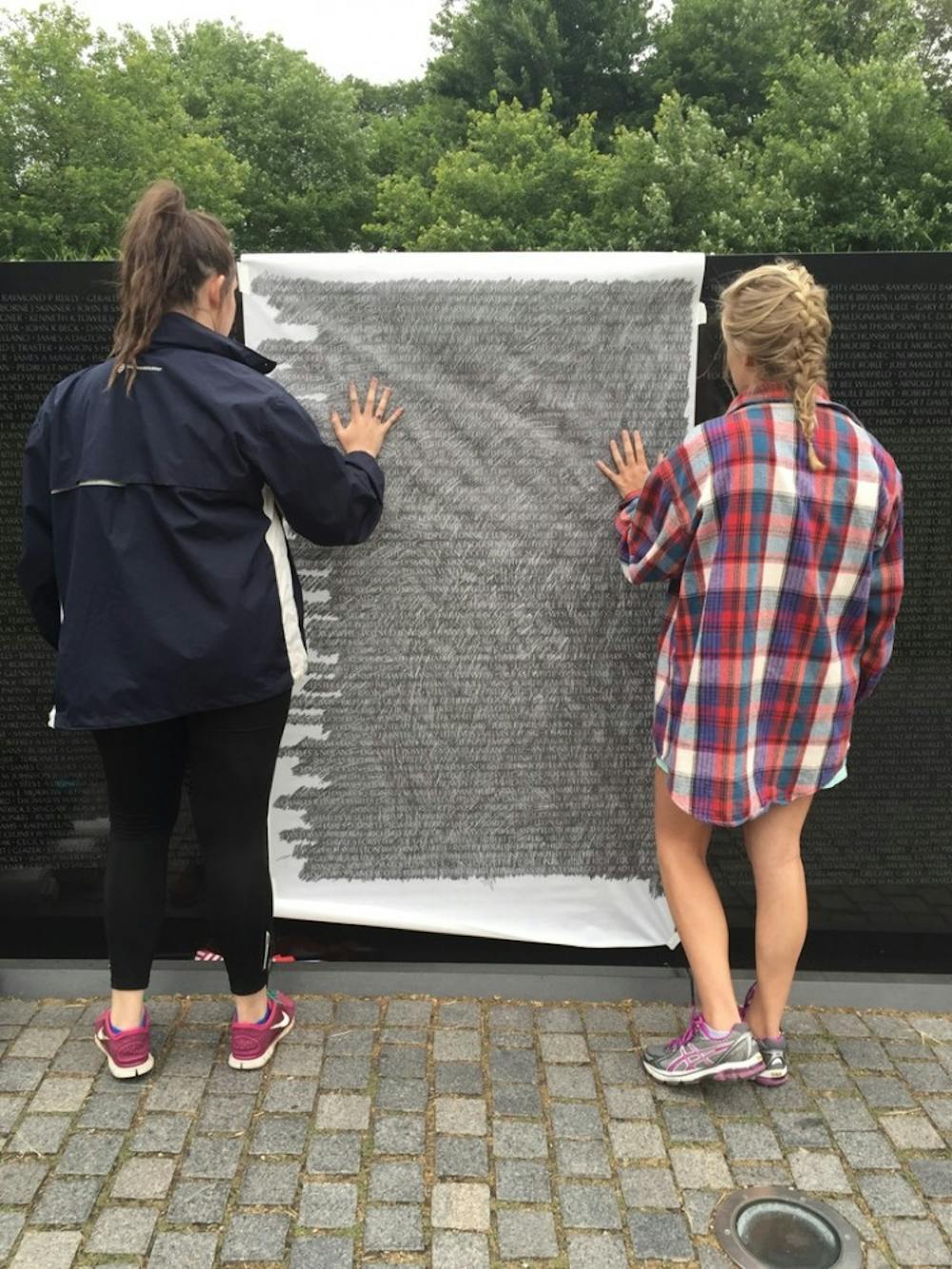

It's about four in the morning at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. The granite wall is illuminated by dim lights that line the pathway. Two panels on the west wall are covered by 10-foot sheets of white paper which, for the past few hours, we've been covering with our thick granite pencils by the light of our phones and a couple headlamps.

For the late hour, a surprising number of people have walked past, some stopping to ask what we're doing, others lighting our work briefly with the flash of their cameras, and a few just silently watching before moving down the path. But no one has had as much to say as this gentleman.

A veteran of the Marine Corp., he is a proud member of the Massachusetts Vigil Society. Every state used to have a chapter of the organization, he explained, but now only his home state is left. Someone from the group stays at the memorial for 24 hours a day every Memorial Day weekend. This is his shift, and he'll be here alone until six in the morning.

Throughout his years of coming to the memorial, he says, he's collected dozens of poems left at the wall-poems from veterans, from family members, from young students-and collected them in scrapbooks. He also wrote a poem about the wall. I ask him what the poem is about.

It's about what the wall has done for him. He says, "It took the pain away."

He points over to the hill at the east end of the memorial, and tells us to come see him there after we're done working. Up on the hill are displayed banners with the names of over 7,000 men and women who were killed serving in Iraq and Afghanistan.

He says after hearing Gold Star Mothers - those who have lost a son or daughter in military service - say they wished they had something like the Vietnam Memorial to commemorate the children they lost in Iraq and Afghanistan, he decided, as a member of one generation of veterans, to honor the next generation's fallen soldiers with a memorial of their own.

By searching for information about the banners, I found his name, Dan Kendall of Brockton, MA, in an article for The Patriot Ledger. It's accompanied by a photo of Kendall and fellow Vietnam veteran Dan Golden in front of the banners standing proudly, arms crossed.

Kendall was one of many people who stopped us that week to ask what we were doing making rubbings of entire panels of the memorial at all hours of the night, and just one of many who, after learning about our project, told us their own stories - about the memorial, about the war, about the friends or uncles or grandfathers whose names are inscribed on the wall.

A few months ago, I got a phone call from my friend Gracie Engle who graduated from high school with me in Vandalia, OH and is now studying history and political science at the University of Alabama.

She was working on a project about PTSD in the military, she explained, and had been watching documentaries and reading articles about the veterans of the Vietnam War, veterans who, unlike those of earlier conflicts, were largely not received as heroes when they returned.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

She wanted to think of them as more than a number but as individuals with names, loved ones, and stories.

When Gracie went to Washington, D.C., for an eighth grade class trip, she had made a rubbing of a name on the Vietnam Memorial, Gary P. Heizer. She brought it home for her father who lost his friend Gary in the war. It made it more real, she said, just to trace over that one name.

So, five years later, she had the idea to make more rubbings - 58, 307 of them, to be exact - every name on all 140 panels of the 247-foot memorial.

She spent the months leading up to our departure date emailing and calling people from the memorial, scouring art supplies sites for materials, and communicating with people from our alma mater, Vandalia-Butler High School, about displaying the panels once they were finished.

West Carrollton Parchment and Converting donated all of our paper which Gracie and her mother prepped by cutting into 10-foot pieces that they rolled and fit into PVC pipes which her father outfitted with handles to act as our carriers for the rubbings.

So early that Tuesday morning we packed Gracie's trunk with luggage, rolls of paper, and 100 graphite pencils and, along with Haley Hamilton, another 2014 Vandalia-Butler graduate and currently a Spanish and international studies major at Miami, we made the 500 mile journey to Washington, D.C.

After D.C. traffic kept us from even getting to the memorial on Tuesday evening, we set out at 6 a.m. on Wednesday expecting to get a lot of work done before the crowds showed up, but soon realized that between the regular stream of tourists, morning joggers, and May's wave of eighth grade tour groups, we could barely weave through the crowd by 10 a.m., let alone set up work on the rubbings.

We decided, then, that we would work by night, toting our tubes of papers and backpack of materials through downtown D.C. once Constitution Ave. had changed from gridlock to a ghost town. We worked until the sun rose.

One morning, members of the Rolling Thunder, a national motorcycle group which started in 1988 to raise awareness about those who were killed or missing in action after Vietnam, arrived at the wall, carrying brushes and buckets of soapy water for their annual cleaning of the memorial.

One of them approached us, warning us what they would be doing, but assured us that they would start at the other end and let us finish. Then, a few of the other men offered to help, taking graphite sticks and working alongside us as we worked our way down the panel. They teased each other after admitting how much doing the rubbings hurt their arms after several names.

Over the course of the week, we adjusted to our nocturnal routine, and our hands grew accustomed to the monotonous back and forth motion of rubbing our sticks of graphite over the names on the wall. We would read the names as we worked, noting popular names, unusual names, familiar names.

That early morning when we met Dan Kendall was our last workday for this year.

We had completed 43 panels total, shy of our goal of completing half but enough to feel like we'd done something, enough to be excited to come back next summer to keep working, enough to have a sense of what 58, 307 fallen means.

When Kendall decided he had distracted us from our work for too long, he said goodbye, apologizing for the time he had taken away from our progress on the panel. We insisted, no, he didn't keep us away from anything; we wanted to talk.

He thanked us. We thanked him. "It's a good thing you're doing here," he said and turned, slowly walking down the dimly lit path, our graphite pencils already scratching away again at the paper.