Reis' Pieces

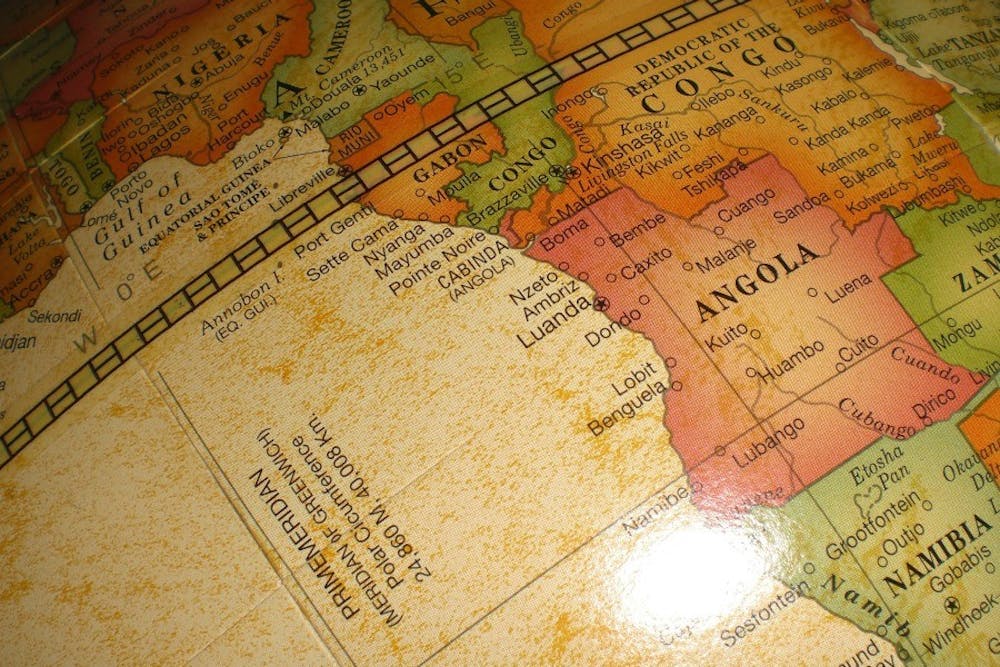

Fifty-four countries, 1.1 billion people, 2,000 languages, but just one name: Africa.

When I returned from South Africa at the end of last summer, everyone from my family to friends and professors asked me about Africa. "Weren't you in Africa?" "How was Africa?" No one asked me in which country I had spent the summer. To most people, it seems, they're all the same.

This is a dangerous ignorance.

What's worse, the chronic misidentification of the world's second largest continent extends beyond my own circle. Discussing Africa as if it were a country is endemic to western media's world news coverage.

A study done by British newspaper The Guardian illustrated the paper's own imprecise reporting. In 2012 and 2013, The Guardian published 5,443 articles that use "Africa" as an all-encompassing descriptor. By comparison, The Guardian published just 2,948 articles that used "Asia" in a similar way. This shows the prejudice that even one of the world's leading news sources has against the continent.

And, it's not just British newspapers. Even the New York Times, journalism's holy grail, has dialed back its coverage, thereby widening the lens through which people see the continent. No longer are there correspondents in each country, embedded with soldiers and warlords. Now, there is the East Africa bureau, tasked with covering Somalia, the Congo and everything in between.

It's a media-wide epidemic. And, not only does this retreat lead to missed stories (five million dead from civil war in the Congo? Ring a bell?), it also breeds generalization. Child soldiers, military coups and the mutilation of female genitalia all become "African problems." They are underreported and, when they do get covered, they are usually poorly written, 300-word accounts that do no justice to the horrors of their topics.

This year's Ebola outbreak only made matters worse.

"Do you have Ebola now?" people would ask, only half kidding, even though the nearest confirmed case was more than 3,500 miles from where I had lived.

The virus should have shed greater light on the continent. It should have spurred an interest in African geography. Instead, the U.S. media fueled an ever hysterical and misinformed population.

Still, few know where to find Guinea, Liberia or Sierra Leone. And, for mainstream America, Ebola and Africa are synonymous.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

This stereotyping is dangerous. It is the building blocks of racism. And, it has implications both in the U.S. and abroad.

At a New Jersey elementary school in October, two Rwandan children missed nearly a month of school because of pressures from the school district and other parents. Even though Rwanda is 2,600 miles away from the nearest Ebola cases, outspoken parents of other children at the New Jersey school told local news, "Anybody from that area should just stay there until all this stuff is resolved. There's nobody affected here let's just keep it that way."

In fact, Rwanda (with zero) has seen fewer Ebola cases than the U.S.

In another instance of outright discrimination, Navarro College, a Texas community college, sent rejection letters to all students applying from Ebola affected countries.

Navarro, ironically, is about 50 miles south of Dallas, ground zero for Ebola in the United States.

The college sent the letters to two Nigerian students. Nigeria, however, was declared an Ebola-free zone in October, about a month sooner than the U.S. was officially free of the virus. The college, however, continued accepting students from Texas and New York - both of which had confirmed cases.

This small-minded view of the continent only fuels xenophobia. It builds a wall between "us" and "them" and it often leads to marginalization.

Look, geography is important - especially now, when African geopolitics has never been more significant. Its population is the world's youngest and its economies are among the world's fastest growing. Innovations from African tech companies are leapfrogging those of "more developed" Western countries (Take Kenya's M-Pesa, for example, the precursor to Apple Pay). Businesses the world over see African markets as ones with large, but untapped opportunity.

What's more, in an era of increasing globalization and connectivity, something that happens on one continent will likely affect the lives of those on another, no matter how distant. So, please, learn some geography, because asking me about Africa is like someone asking you about North America.