By Rick Momeyer, professor emeritus

Creative Commons Photo

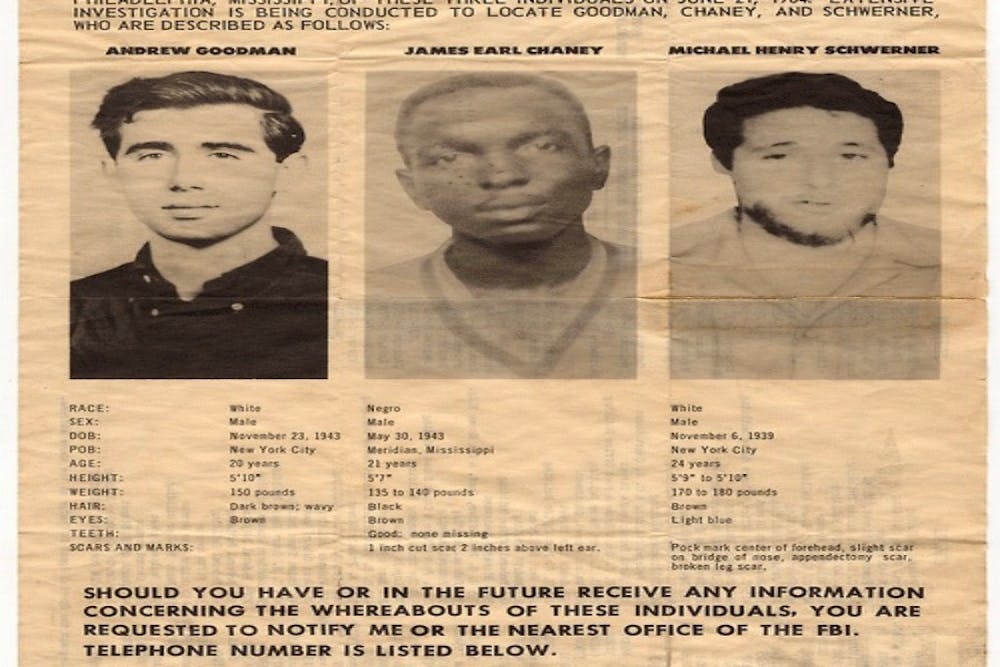

My FBI file and why it should concern you as a Miami Student today

When I was an undergraduate at Allegheny College, beginning in 1960, I was greatly benefitted by three different opportunities that each in its own way transformed my life. The first was to have some extraordinarily good teachers -teachers who took a very raw, ill prepared, but earnest young person seriously and challenged me to see the world in very different ways than I had acquired in my first 18 years. The second was the occasion when Bayard Rustin visited campus, in the fall of 1961, to enlighten us as to what was happening in the burgeoning civil rights movement. The third, growing directly out of these first two, was to go to Fisk University as an exchange student the second semester of my second year, winter/spring of 1962. Taken together, these three events have led to living a very different, and I believe, far more rewarding, life than the one I had envisioned at 18. It also brought me to being noticed by the FBI and began a long period of surveillance.

It is for good reason John D'emilio, in his biography of Bayard Rustin, subtitles the book "The Lost Prophet." Rustin was a life long advocate for nonviolence, a close adviser to Dr. King, and the organizing genius behind the great March on Washington in 1963. After he addressed a full house in the Allegheny College chapel, he sat down with about 12 of us for further discussion. Rustin's opening remark was: "How come you all decided to come to a segregated college?" That was a revelation to us, who had not thought of Allegheny as segregated; merely as lacking a significant population of Negro students.

So some of us set out to change this, mostly by proposing to help the admissions office recruit students of color. In the course of that effort, we learned that other historically white colleges (Colby, Wooster, Grinnell, and more) had for some years conducted one-on-one semester long student exchanges with historically black colleges. At Allegheny, we arranged such an exchange with Fisk University in Nashville, and in January of 1962 three students from each institution changed places.

The fourth day at Fisk, a picnic was held in Nashville's park with a replica of the ancient Greek Parthenon, and the other two Allegheny exchange students and I were invited. The rather bizarre replica of the Parthenon was of little interest; the other picnickers were so engaging, even captivating, for the persons they were and the stories they had to tell.

Virtually all of the other 20 people at this well-integrated picnic were veterans of the "Nashville Movement," the anti-segregation campaign that for two years had been one of the largest - and in some ways, most successful - parts of the protest and sit-in movement sweeping campuses and communities throughout the South. Probably half were also veterans of the previous summer's Freedom Rides, most of whom were fairly fresh from Mississippi's infamous Parchman Prison where Freedom Riders who made it as far as Jackson were routinely arrested and hustled off to spend the next three months. Their stories were compelling, and after they had been told, someone started playing a guitar and all broke out singing freedom songs that had so empowered and sustained the demonstrators against segregation and its attendant insults to human dignity.

I would venture to suggest that had you been 19 years old in 1962, as I was, and in the presence of people as smart, courageous, committed to justice, energetic and funny, you, too, would have wanted to be part of what they were about. Among those at the picnic were: Rev. James Lawson, a theology graduate student who had been expelled from Vanderbilt University for his Movement activities, and Fisk students Bernard Lafayette and John Lewis. Lawson is the Methodist minister who was a close ally of Martin Luther King and tutored Dr. King in Ghandian philosophy. Lafayette is a long time organizer of peace education and a distinguished professor of religious studies at Emory University. And John Lewis has been Atlanta's Congressional representative for more than 20 years and is certainly the most admired and respected member of Congress on either side of the aisle.

On my seventh day in Nashville, I went to a workshop on nonviolence taught by Rev. Lawson to learn why all participants in the Movement were expected to return love for hate and how to protect themselves when physically assaulted. I was never entirely persuaded of the first, but learned much from the more practical part of the workshop that proved useful in days to come.

On my 10th day in Nashville, Peter Schwartz, another Allegheny exchange student, and I joined John Lewis and two other black students in seeking service at an upscale downtown restaurant, the Cross Keys. We got no service; instead, we got arrested, ostensibly for disturbing the peace of a racially segregated facility even though all we had done was sit at a table in our best clothes and politely request menus. We spent the weekend in jail (segregated cells) and went before a magistrate for a hearing on Monday morning. But the owner of the Cross Keys failed to appear to testify, and we understood the judge to dismiss the charges. We got back to campus in time to meet our classes.

But the Davidson County District Attorney had other ideas. Unbeknownst to our attorney or us he sought and obtained a Grand Jury indictment on three felony charges, all stemming from laws enacted in the 1890s when racial segregation was being codified in the wake of Reconstruction's failures. We learned this two months later, but inasmuch as the DA wanted to test the constitutionality of these laws, we were rather pleased. We thought it might become an important case and go to the Supreme Court. But it was not and it did not.

More to the point, this was the beginning of my FBI file. I learned this 14 years later in 1975 when, as a young, still untenured assistant professor at Miami, I exercised my right under the recently enacted "Freedom of Information" (FOI) law allowing citizens access to secret files the government might have kept on their activities. I did not expect to find this five-page indictment in it, but I did expect there would be a file because in 1964 I made a complaint to the FBI and they had promised to investigate and get back to me. They had not gotten back.

When informed that the FBI would send me the file after I sent them $7.60 (10 cents-a-page copying charge), I thought, vaingloriously: "Damn, I'm important! They have 76 pages on me." But when I got the file and read it, I was considerably less impressed with myself and more impressed with the FBI. Seventy-one of those 76 pages were the full field report filed by the several agents that Burke Marshall, Bobby Kennedy's chief Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, had assigned to address my complaint.

In 1964, after graduating from Allegheny, I was hired onto the staff of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (at a standard salary of $9.64 a week, when, as it only occasionally did, SNCC had it) and assigned to work with the SW Georgia Project, eventually landing in very rural Colquitt County. (First, however, I came to Oxford, OH to help with the training for Freedom Summer volunteers. That's a whole other, oft told story).

One early evening in Moultrie, where we lived, Herman Kitchens, the African-American fellow SNCC staff member with whom I was partnered, and I were shot at. We thought we were probably shot at by some young toughs who had been hassling black kids seeking service at the local Dairy Queen. I reported this to the local sheriff; he could have cared less. So with SNCC headquarter's encouragement, I went to the local FBI agent, Royal McGraw. He did not seem to care any more than the sheriff, but he took my statement and said, "we will get back to you."

As it happened, the FBI "solved" the case and took it to the local prosecutor. Apparently, he quickly dropped it, judging that he'd never get a conviction. No one told me. Nonetheless, I was impressed with the FBI's effort.

I should have been less impressed. And this is the first reason you should be concerned about my FBI file and why it is a threat to you. It is not what was in the file that should concern you, but what was left out. For what was left out of the file I was sent in 1976 were 40 pages of surveillance reports on Miami University student groups in 1970, 1971 and 1972. In 1976, those files were stamped "Classified."

I learned this nearly 30 years later when, at Miami, we were planning to celebrate Freedom Summer and Miami's contributions to it with a 40th Anniversary Reunion/Conference.

For years, we had been trying to locate a list of volunteers who had come to Oxford for training in order to reach and include as many as were available in the Reunion/Conference. There was reason to think the FBI might have such a list, given their propensity for spying on (and more, through the notorious "cointel" [counter intelligence] program) provoking and disrupting groups seeking social change. So I asked for my file again.

This time, I was stonewalled for nearly a year. I repeated the request. They told me I had no file. I reminded them that in 1976 they had a file. What had happened to it? They found it. This time it was over 200 pages long. And I did not have to pay 10 cents per page to get it!

"Damn," I thought again, being sometimes a slow learner, "I'm important." But again, I was mistaken: all the additional pages were not really about me, but consisted of the list of volunteers and staff who came for Freedom Summer training, each identified by name, home town, and religious affiliation in 1964, and the earlier mentioned surveillance of Miami student groups from 1970-73. Both had been withheld in 1976.

Unfortunately, the censors had blacked out all the names on the list, with the exception of mine and, as it happened, Stokely Carmichael. But then, there never was any possibility of hiding the larger than life Stokely, founder of the original Black Panther Party in Lowndes County, Alabama and later a leader of the Black Power Movement.

I suppose every conscientious citizen should be concerned with FBI stonewalling in the light of the FOI Act, both for its slowness of response and more for its refusal to share a list of people who are to be celebrated for their contributions to social progress and their raw courage, especially working in Mississippi for civil rights in 1964. Maybe some few folks would be concerned that the FBI was compiling a dossier on a generally mild mannered professor of philosophy. But these need not be particular concerns to you as a student today; rather, the surveillance of campus groups with the collaboration of other students and university employees should be an ongoing concern and perceived as a direct threat to each of us still today.

The groups spied upon in 1970-72 were anti-war groups, chiefly the "Student Mobilization Committee," organizing protests on and occasionally off campus against the war the U.S. government was waging against Vietnamese peoples (and as we learned so painfully in 1970, against Cambodians and Laotians as well). These were groups that held open meetings and invited anyone and everyone to attend, which worked at publicizing and recruiting attendance. There was nothing illegal or nefarious in their very public planning and actions. And yet the government felt entitled to secretly spy on them, and for years, to keep that spying classified as secret.

The names of the spying agents are all blacked out in my file, but a close reading reveals that they had to be either or both other students or student personnel staff employed by Miami University. The reports were regularly submitted to the FBI office in Cincinnati (there was also spies reporting to Cincinnati from Antioch College and Ohio State University). We do not know, and likely will never know, whether some of these spies were also agent provocateurs. We do not know, and will likely never know, how all of this information was used by the government, what opportunities or rights it was used to curtail.

Heavily redacted versions of these reports landed in my file, first, I suppose, because I already had a file, but secondly, because I was the faculty adviser of record to the student organizations. In my 44 years at Miami I was faculty adviser, albeit a rather distant one, to more than half a dozens student organizations, always on the premise that students were entitled to organize around whatever their concerns were and the university required they have a faculty adviser.

But why is my FBI file a threat to today's students, and not just a matter of possibly interesting historical fact? I would argue it should concern you because it is illustrative of the risk each of us is under from those who would presume themselves entitled to collect all manner of information about us and use it to whatever ends they wish without being accountable to those whose privacy they have so egregiously invaded. These days such monitoring of even our most innocent activities as shopping on line or posting to social media sites or talking on the telephone or writing an email or text are subject to surveillance. What we now call "data collection," and "megadata mining" rather than intrusive spying in this Brave New World of doublespeak is nearly ubiquitous.

We know both government and corporations engage in massive data collection and analysis; we know very little about what they do with this information and still less about what they could do with it. We should all regard ourselves as indebted to Edward Snowden for whistle blowing on National Security Administration (NSA) activities. At the same time, most of us appear oddly indifferent to the risks such massive government (to say nothing of corporate) intrusion imposes on our lives, on what use might be made of this information presently and in the future.

Has the world changed so much from the historical spying and the uses and abuses of collected information that I recounted here? In some ways it has, and for the better. We now have better developed protection of privacy policies for both citizens and students. How effective they are in this new era of information technology is an open question. But in some ways, we are clearly far worse off, for the enhanced capacity to spy on each of us - without having to send real people into our classrooms and meetings to do so - is far more powerful than the old ways. Phone tapping, for instance, no longer requires actual physical intrusion on our phones, or even a court order: the NSA can and has tapped virtually all our phones by electronically intercepting signals or coercing or enlisting the cooperation of telecommunications corporations to provide records.

Do we have a government today that is less fearsome than one of yore where "intelligence gathering" was overseen by the likes of J. Edgar Hoover, archenemy of Dr. King who once tried to coerce King into killing himself and with a disposition to see a fearsome "communist" hiding under every bed, in every closet, and manipulating all those who sought progressive change in the status quo?

Well, we aren't fighting the cold war and Communism anymore, but arguably we have simply substituted the "war on terrorism" and "terrorist" for these perceived enemies. Further, we have a national policy that seems to authorize our secret armies to assassinate even U.S. citizens believed by the "intelligence" agencies to be "terrorists," or even more problematically, "potential terrorists," notwithstanding that there has been no due process of law, no trial, no jury of peers, to ascertain these suspicions are well-founded. Just send a drone - not James Bond - to kill suspects.

Perhaps of greatest concern is not what we already know of government and corporate spying but what we don't know. What is being kept from our eyes today that even Snowden did not have access to? Will we only learn 30 years or more later, as I did, what this is? Will we ever know?

The concern here is not based on a Tea Party rant against big government as such, or a right wing Libertarian notion of freedom as entirely egoistic and individualistic. It is a concern I believe is shared by every conscientious citizen of any society striving for justice, equality and greater democracy.

I and my entire generation bear some responsibility for not being more inquisitive, more proactive, more demanding in countering the spying widely done on us in the past, a set of practices that left insufficiently challenged has helped lead us to the present where spying is still more rampant and the uses to which it is being put even darker. But even more responsibility is borne by those who are the subjects of contemporary invasions of privacy and indifferent to it, who fail to resist or inquire, or assert their right to privacy. Are you and your friends at Miami University at all concerned by constant surveillance of your life? And if you are, what are you doing about it?