In an effort to clarify consent on college campuses with "yes means yes," feminists have done just the opposite and codified bad language into law.

Last September, California passed SB 967, the first "yes means yes" law in the country for college campuses.

The law codifies affirmative consent, defined as, "Affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity."

Not necessarily terrible, although there should still be room for nonverbal cues. I find it hard to imagine that couples engaging in sex always, unequivocally get an affirmative, "Yes, let's have sex," before doing so. Body language is a form of communication, after all.

The next bit is where it gets more troubling, "Affirmative consent must be ongoing throughout a sexual activity and can be revoked at any time."

Most certainly, a woman or a man ought to be able to end a sexual activity at any point in time. Initializing doesn't grant consent throughout.

However, the "ongoing throughout a sexual activity," ought to raise eyebrows of any person who's ever had sex. Under this definition of consent, almost every sexual encounter would be classified as rape.

Esquire magazine did a long-form story on an illuminating incident that occurred at Occidental College in 2013. The names of the individuals were changed.

John, an 18-year-old, was drunk from a day of freshman-jock initiation games. Jane, 17, was also drunk. They met in John's dorm room, where they were embracing. One friend described it as Jane "trying to kiss John and dance with him ... and John trying to get [the two friends] to leave."

Then Jane did leave and they exchanged text messages, with John wanting Jane to come back and leave her friends. Below is the rest of the exchange, according to Esquire:

JANE: Okay do you have a condom?

JOHN: Yes.

JANE: Good give me two minutes.

JOHN: Come here.

JANE: Coming.

JOHN: Good girl.

Jane was the vomiting-in-a-trash-can drunk. When they met in John's dorm room, she again asked about a condom, then performed oral sex on him. Two different people interrupted and one of them repeatedly asked Jane if she was okay, to which she replied, "Yes, I'm fine."

Afterward, Jane texted her friends a smiley face.

The next day, neither one remembered much. Three months later, John was expelled by Occidental for sexually assaulting Jane.

The LAPD found "insufficient evidence to charge John with a crime" under criminal law. Unfortunately, the LAPD confirmed every fear a rape victim has about reporting to the police. When Jane went to report the complaint to them, a desk officer asked Jane if John had forced her into his room, to which Jane said he had not. The desk officer then said, "Well then, it's not rape..."

It's well-known at this point how awful police can be when dealing with cases of sexual assault and rape. However, turning that over to universities seems ill-fated. At the university level, they rely on the preponderance of evidence standard, "Is it more likely or not that something bad happened here?"

Quite the low standard for something as serious as rape.

Under Occidental's ruling, John, just as drunk as Jane, was found responsible for his actions, even though it was acknowledged in the hearings that John was "more intoxicated than he had ever been" and that this level of intoxication impaired his ability to assess Jane's incapacitation, "his state of mind had no bearing."

For clarification on incapacitation, Scott Berkowitz, the president of the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network, told Esquire, "Generally it's understood to mean that drugs or alcohol have had such an effect on [a victim] that they're not in a position to express consent."

It's hard to see how John and Jane's situation isn't just a regretful hookup based on poor judgment. A bad hookup and/or drunk sex does not necessarily qualify as a rape.

And now John's branded with a scarlet letter of rape based on a double standard applied to men and women.

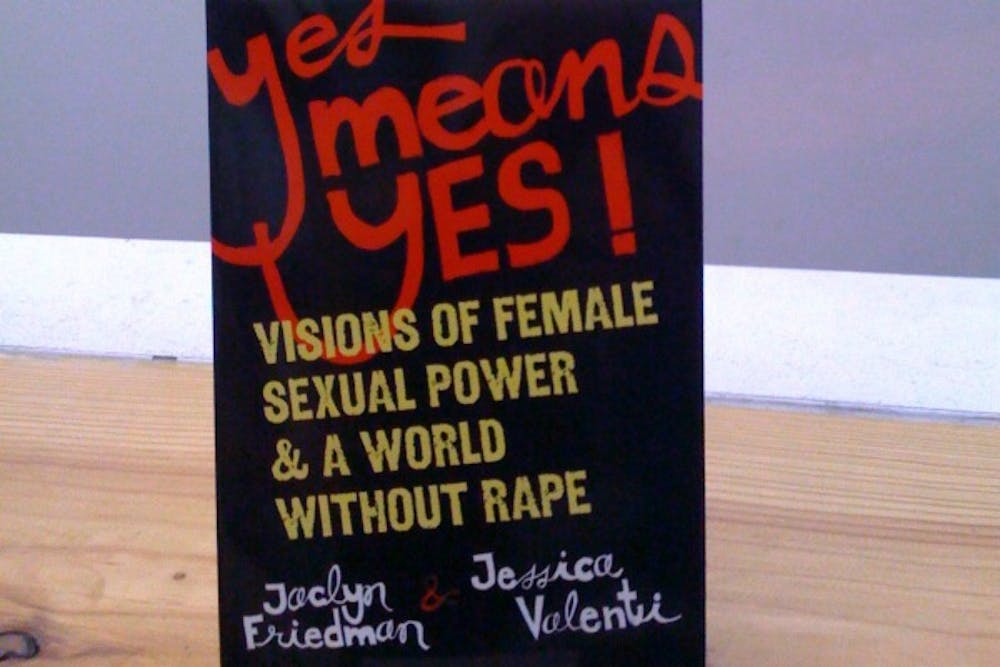

Far from clarifying consent, feminists have gone too far in contributing to the muddled waters. Indeed, it's frustrating for a movement that traces its lineage back to the sexual liberation of women to take this track.

Furthermore, this bill is troubling because it obfuscates the problem of rape: it's characterizing it as a communication problem.

David Lisak and Paul Miller co-authored a 2002 study that shows the real problem is with serial predation and rape on college campuses. They found that repeat rapists averaged 5.8 rapes each.

In other words, most rape on college campuses is perpetrated by repeat offenders, which speaks to the larger problem of college administrations being abysmal at getting these predators off the campus.

"Of the 120 rapists, 76 (63.3 percent) reported committing repeat rapes, either against multiple victims or more than once against the same victim," the study found.

These types of individuals, more broadly, are serial criminals. Beyond repeat rape, they also engage in other forms of interpersonal violence, like battery, physical abuse and other forms of sexual assault.

Furthermore, this helps to clarify the statistical discussion in this newspaper back in March over the one in 12 number, wherein one in 12 men have admitted to the legal definition of rape, cited by Emily Tate in her column.

As the co-authors noted in their study, their data gets at the seeming paradox here, where there's a discrepancy between the high numbers of women sexually victimized and the low numbers of men admitting to the legal definition of rape. It's because a small number of men are responsible for the high levels of victimization, i.e. serial rapists.

Aside from wanting to clarify the number dispute, I bring this up because it's important to the discussion on consent, too. A serial rapist is not worried about whether the woman he's about to rape will consent to him or not. Either through force or drugs and alcohol, they will assert their attempts at power and control regardless.

Rape is not a miscommunication problem, largely.

The "yes means yes" law is not only codifying confusing language over sexual assault, but it seems to muddle this understanding of serial rape.

Nevertheless, the bill does have good language that should be codified, to be sure. That the existence of a dating relationship doesn't indicate consent or that someone can't consent if incapacitated due to drugs and alcohol or if they're asleep. But this other language conceives of sex too conservatively and takes autonomy away from women.

We can protect against sexual assaults and rape on college campuses while still respecting a more realistic understanding of sex. Even more, we can do this while still maintaining the agency of women.