Milam's Musings, milambc@miamioh.edu

The free market's beauty, contrary to the perspective of its detractors and defenders, lies within its collectivism. Which is to say, the free market works precisely because we work together, not off on our own individualized islands.

It troubles me deeply that the free market is so scorned and misunderstood, especially among my peers who are feeling the Bern. I see it as, on the whole, reflecting what humanity can accomplish together.

Imagine where we would be without the division of labor, specialization of knowledge, globalization, trade and the price system.

It is without those mechanisms that we end up on our own individualized islands, fending for ourselves. As in, how it was for most of recorded history, which was unbearably brutish and bleak for humanity.

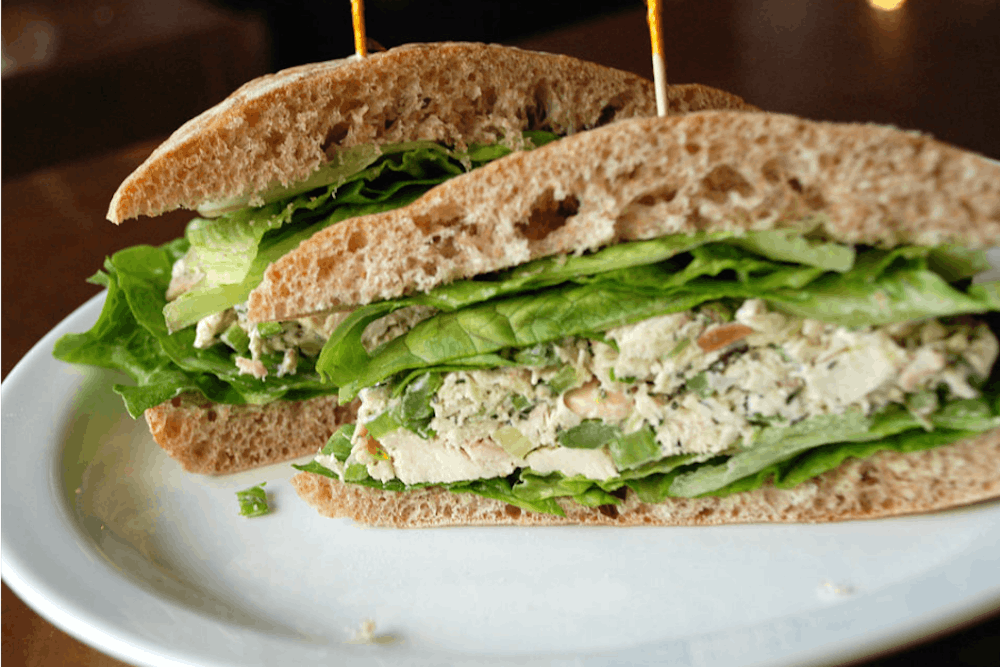

Take, for example, the process required to build a simple sandwich. Right now, I can walk three feet into my kitchen, grab two slices of wheat bread, slap some lunch meat and mustard on it and have a tasty snack.

To acquire that bread, lunch meat and mustard, I just have to drive to the grocery store less than eight minutes from my house.

There are millions of people involved in the process of getting the wheat bread, the lunch meat and the mustard to my kitchen, however. Most have no clue of the machinations of the other. Most likely don't care about my personal need and desire to have a sandwich. And yet.

Furthermore, I didn't even take into consideration the materials needed to wrap and seal the bread, the lunch meat and the mustard. Or the millions more people that made the car in which I drove to the grocery store. Or the construction that went into creating the grocery store.

Once you start to unpack all the components that go into how a simple sandwich arrives on my plate, it's extraordinary and reveals the true beauty of the market.

But imagine, instead, if I had to make that sandwich entirely by myself. Luckily, we don't have to imagine it because YouTuber, Andy George, last September tried just that.

He spent six months and $1,500 to do it.

Enjoy what you're reading?

Signup for our newsletter

George grew his own vegetables, made his own salt from the ocean water, milked a cow for cheese, ground his own flour after harvesting the wheat, collected his own honey and killed a chicken for the meat.

Now consider the "givens" he worked with, too: he had an oven, pots and pans - which, mind you, were inside a house presumably with air conditioning - and used an airplane to get to the ocean to acquire the salt.

Of course, there's the various clothing items George wore while doing this. He actually has another video where he details the 10 months and $4,000 it took him to make a suit from scratch.

Further, then, consider that in six months, he changed clothes, which meant he had to wash his clothes. I could do a whole article on how extraordinary the washing machine is and how much it saved humanity (and particularly women), but instead, I'll just refer you to Hans Rosling's TED Talk, "The magic washing machine."

If we go back to unpacking the ways in which those aforementioned items get to the individual, you can begin to appreciate the overwhelming complexity of food supply chains, which appear simple to us.

Life would be terrible if we had to make our own food every meal, every day. And that's just ourselves. Never mind if we have a family to feed, too.

But there's another under-appreciated beauty to this, which is that wealth accumulation gives us our most valuable commodity: time.

That I don't have to spend most of my existence making my own food merely to survive means I'm free to live and embrace leisure.

As in, I can think, dream, read, listen to Mozart, watch Netflix or myriad other activities, including writing this article and attending higher education, which weren't possible for most of recorded human history except for the most well off (and even they, compared to today, had it fairly terrible).

Moreover, that these now simple chores used to be laborious meant the entire family, including children, were tasked with helping, rather than going to school or being kids.

That "being a kid" and being able to play was able to become a thing at all is attributable to wealth accumulation and market exchange.

None of which is to say we shouldn't care how our food is made and desire that it's made humanely and with the best considerations of the environment involved behind it, but rather, that we should appreciate the complex mechanisms in place, which aren't directed by some government bureaucrat, that make it happen.

None of which is to say there are not still those who endure extreme poverty in fetching for their own food and/or having to make and clean their own clothes without the benefit of the washing machine. In fact, five billion people don't have access to a washing machine.

As Rosling points out in his Ted Talk, most of the people cleaning clothes by hand are women. As you can see then, there's a strong feminist argument to be made for the "magic" of the washing machine.

The extreme poverty comes from a lack of market exchange and industrialization, among other factors, like education, colonialism, imperialism and corrupt governments.

None of which is to say there aren't both valid criticisms of consumerism and materialism, as well as the uglier elements of our corporatist economy (meaning, the collusion of big business and government, which decidedly is not free market).

But as Steve Horowitz, a professor of economics explains, "Market-driven innovation has allowed machines to do our work for us and has brought us new and better products to make us cleaner and healthier, enabling humans - and particularly women - to have the time and health to do the things we love and that make us smarter and happier."

I understand that some reading this may think, "Yeah, but unions and government policies gave us the 40-hour work week and the weekend, child labor laws, safety standards in food to produce that sandwich, the roads to transport it to the grocery store and so forth."

If I had more space, I'd love to dispel a few of those myths, but for the sake of argument, let me grant all the aforementioned. Even that being the case, market exchange is still a beautiful web of complexity that's under-appreciated.

I find irony in the fact that wealth accumulation grants the anti-consumerist the luxury of more time, so that the anti-consumerist can rail against the mechanism which gave him or her more time.

My challenge to those who would reject market exchange, the price system, free trade and globalization is to demonstrate how an alternative system would make our lives better, especially the least well off.

In fact, just start with explaining how a sandwich would get to my plate and millions of other plates.